History of the Study

of Locomotion

History of the Study

of Locomotion

Instruction concerning a dislocation of a vertebra of the neck: if you

examine a man having a dislocation of the a vertebra of his neck, should

you find him unconscious of his arms and legs on account of it......then

you should say an ailment which cannot be treated

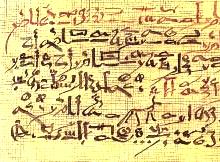

The seventeen columns on the recto comprise the first surgical treatise

thus far discovered. It consists exclusively of case reports, systematically

organized - beginning with injuries of the head and proceeding downward

through the body, like a modern treatise on anatomy. The treatment of these

injuries is rational and chiefly surgical; there is resort to magic in

only one case out of the forty-eight cases preserved. Each case is classified

by one of three different verdicts: (1) favorable, (2) uncertain, or (3)

unfavorable. The third verdict, expressed in the words, 'an ailment not

to be treated,' is found in no other Egyptian medical treatise. This unfavorable

verdict occurring fourteen times in the Edwin Smith Papyrus marks a group

of cases (besides one more case) which the surgeon cannot cure. It is likely

that the patients described in the 48 cases were injured by falls (maybe

from working on monuments or buildings) or were victims of battle (many

wounds appear to be caused by spears, clubs or daggers.) The brain is mentioned

7 times throughout the papyrus. However, there is no use of the word "nerve."

The

48 cases contained within the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus concern:

The

48 cases contained within the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus concern:

-

27 head injuries (cases #1-27)

-

6 throat and neck injuries (cases

#28-33)

-

2 injuries to the clavicle (collarbone)

(cases #34-35)

-

3 injuries to the arm (cases #36-38)

-

8 injuries to the sternum (breastbone)

and ribs (cases #39-46)

-

1 injury to the shoulder(case #47)

-

1 injury to the spine (case #48)

Edwin Smith, was born in Connecticut in 1822, the year that Egyptian hieroglyphic

was first deciphered. On January 20, 1862 in the city of Luxor, Smith bought

the surgical papyrus from a dealer named Mustapha Aga. Two months later

the same vandals sold him the remaining fragments glued onto a dummy roll.

Although Smith recognized the fraud, pieced the two together, and made

an attempt at translation, it was not until 1930 that James H. Breasted

translated the treatise and established its importance. According to Breasted,

the Edwin Smith Papyrus is a copy of an ancient composite manuscript

which contained, in addition to the original author's text (3000-2500 B.C.),

a commentary added a few hundred years later in the form of 69 explanatory

notes (glosses). It contains 48 systematically arranged case histories,

beginning with injuries of the head and proceeding downward to the thorax

and spine, where the document unfortunately breaks off. These cases are

typical rather than individual, and each presentation of a case is divided

into title, examination, diagnosis, and treatment.

The

scribe of over 3,500 years ago had copied at least eighteen columns of

the venerable treatise and had reached the bottom of a column when, pausing

in the middle of a line, in the middle of a sentence, in the middle of

a word, he laid down his pen and pushed aside forever the great Surgical

Treatise he had been copying, leaving 15½ inches (39 cm.) bare and

unwritten at the end of his roll.

The

scribe of over 3,500 years ago had copied at least eighteen columns of

the venerable treatise and had reached the bottom of a column when, pausing

in the middle of a line, in the middle of a sentence, in the middle of

a word, he laid down his pen and pushed aside forever the great Surgical

Treatise he had been copying, leaving 15½ inches (39 cm.) bare and

unwritten at the end of his roll.

Case Eight

Title: Instructions concerning a smash in his skull under the skin of his

head.

Examination: If thou examinest a man having a smash of his skull, under

the skin of his head, while there is nothing at all upon it, thou shouldst

palpate his wound. Shouldst thou find that there is a swelling protruding

on the out side of that smash which is in his skull, while his eye is askew

because of it, on the side of him having that injury which is in his skull;

(and) he walks shuffling with his sole, on the side of him having that

injury which is in his skull...

Treatment: His treatment is sitting, until he [gains color], (and)

until thou knowest he has reached the decisive point....

Gloss: As for: "He walks shuffling with his sole," he (the surgeon)

is speaking about his walking with his sole dragging, so that it is not

easy for him to walk, when it (the sole) is feeble and turned over, while

the tips of his toes are contracted to the ball of his sole, and they (the

toes) walk fumbling the ground. He (the surgeon) says: "He shuffles," concerning

it...

Case Thirty-One

Title: Instructions concerning a dislocation in a vertebra of [his]

neck. Examination: If thou examinest a man having a dislocation in a vertebra

of his neck, shouldst thou find him unconscious of his two arms (and) his

two legs on account of it, while his phallus is erected on account of it,

(and) urine drops from his member without his knowing it; his flesh has

received wind; his two eyes are bloodshot; it is a dislocation of a vertebra

of his neck extending to his backbone which causes him to be unconscious

of his two arms (and) his two legs. If, however, the middle vertebra of

his neck is dislocated, it is an emissio seminis which befalls his phallus.

Diagnosis: Thou shouldst say concerning him: "One having a dislocation

in a vertebra of his neck, while he is unconscious of his two legs and

his two arms, and his urine dribbles. An ailment not to be treated."

Gloss: As for: "A dislocation in a vertebra of his neck," he is speaking

of a separation of one vertebra of his neck from another, the flesh

which is over it being uninjured; as one says, "It is wnh," concerning

things which had been joined together, when one has been severed from another.

Breasted, J.H., The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, Chicago: University

of Chicago Press, 1930.

Plato (428-348 BC)

First, then, the gods, imitating the spherical shape of the universe,

enclosed the two divine courses in a spherical body, that, namely, which

we now term the head, being the most divine part of us and the lord of

all that is in us: to this the gods, when they put together the body, gave

all the other members to be servants, considering that it partook of every

sort of motion. In order then that it might not tumble about among the

high and deep places of the earth, but might be able to get over the one

and out of the other, they provided the body to be its vehicle and means

of locomotion; which consequently had length and was furnished with four

limbs extended and flexible; these God contrived to be instrumnets of locomotion

whith which it might take hold and find support, and so be able to pass

through all places, carrying on high the dwelling place of the most sacred

and divine part of us. Such was the origin of legs and hands, which for

this reason were attached to every man.

Timaeus (360

BC), translated by Benjamin Jowett

Hippocrates (460-370 BC)

Hippocrates (460-370 BC)

When, then, a dislocation has not been reduced,

but has been misunderstood or neglected, the leg, in walking, is

rolled about as is the case with oxen,

and the weight of the body is mostly supported on the sound leg, and the

limb at the flank, and the joint where

the dislocation has occurred is necessarily hollow and bent, while on the

sound side the buttock is necessarily rounded.

For if one should walk with the foot of the sound leg turned

outward, the weight of the body would be

thrown upon the injured limb, but the injured limb could not carry it,

for

how could it? One, then, is forced in walking

to turn the leg inward, and not outward, for thus the sound leg best

supports its own half of the body, and

also that of the injured side. But being hollow at the flank and the hip-joint,

they appear small in stature, and are forced

to rest on a staff at the side of the sound leg. For they require the

support of a staff there, since the nates

inclines to this side, and the weight of the body is carried to it. They

are

forced also to stoop, for they are obliged

to rest the hand on the side of the thigh against the affected limb; for

the

limb which is injured cannot support the

body in changing the legs, unless it be held when it is applied to the

ground. They who have got an unreduced

dislocation inward are forced to put themselves into these attitudes, and

this from no premeditation on their part

how they should assume the easiest position, but the impediment itself

teaches them to choose that which is most

conformable to their present circumstances. For persons who have a

sore on the foot, or leg, and cannot rest

upon the limb, all, even children, walk in this way; for they turn the

injured

limb outward in walking, and they derive

two advantages therefrom, to supply two wants; the weight of the body

is not equally thrown upon the limb turned

outward, as upon the one turned inward, for neither is the weight in a

line with it, but is much more thrown upon

the one under the body; for the weight is in a straight line with it, both

in

walking and in the shifting of the legs.

In this position one can most quickly turn the sound limb under the body,

by walking with the unsound limb outward, and the sound inward. In the

case we are now treating of, it is well that

the body finds out the attitudes which

are the easiest for itself. Those persons, then, who have not attained

their

growth at the time when they met with a

dislocation which is not reduced, become maimed in the thigh, the leg,

and the foot, for neither do the bones

grow properly, but become shortened, and especially the bone of the thigh;

and the whole limb is emaciated, loses

its muscularity, and becomes enervated and thinner, both from the

impediment at the joint, and because the

patient cannot use the limb, as it does not lie in its natural position,

for a

certain amount of exercise will relieve

excessive enervation, and it will remedy in so far the deficiency of growth

in

length. Those persons, then, are most maimed

who have experienced the dislocation in utero, next those who have

met with it in infancy, and least of all,

those who are full grown. The mode of walking adopted by adults has been

already described; but those who are children

when this accident befalls them, generally lose the erect position of

the body, and crawl about miserably on

the sound leg, supporting themselves with the hand of the sound side

resting on the ground. Some, also, who

had attained manhood before they met with this accident, have also lost

the faculty of walking erect. Those who

were children when they met with the accident, and have been properly

instructed, stand erect upon the sound

leg, but carry about a staff, which they apply under the armpit of the

sound

side, and some use a staff in both arms;

the unsound limb they bear up, and the smaller the unsound limb, the

greater facility have they in walking,

and their sound leg is no less strong than when both are sound. The fleshy

parts of the limb are enervated in all

such cases, but those who have dislocation inward are more subject to this

loss of strength than, for the most part,

those who have it outward.

Part 52

When persons have attained their full growth

before meeting with this dislocation, and when it has not been

reduced, upon the subsidence of the pain,

and when the bone of the joint has been accustomed to be rotated in

the place where it is lodged, these persons

can walk almost erect without a staff, and with the injured leg almost

quite straight, as it does not admit of

easy flexion at the groin and the ham; owing, then, to this want of flexion

at

the groin, they keep the limb more straight

in walking than they do the sound one. And sometimes they drag the

foot along the ground, as not being able

to bend the upper part of the limb, and they walk with the whole foot on

the ground; for in walking they rest no

less on the heel than on the fore part of the foot; and if they could take

great steps, they would rest entirely on

the heel in walking; for persons whose limbs are sound, the greater the

steps they take in walking, rest so much

the more on the heel, while they are putting down the one foot and raising

the opposite. In this form of dislocation,

persons rest their weight more on the heel than on the anterior part of

the

foot, for the fore part of the foot cannot

be bent forward equally well when the rest of the limb is extended as

when it is in a state of flexion; neither,

again, can the foot be arched to the same degree the limb is bent as when

it

is extended. The natural state of matters

is such as has been now described; and in an unreduced dislocation,

persons walk in the manner described, for

the reasons which have been stated. The limb, moreover, is less fleshy

than the other, at the nates, the calf

of the leg, and the whole of its posterior part. When this dislocation

occurs in

infancy, and is not reduced, or when it

is congenital, in these cases the bone of the thigh is more atrophied than

those of the leg and foot; but the atrophy

of the thigh-bone is least of all in this form of dislocation. The fleshy

parts, however, are everywhere attenuated,

more especially behind, as has been stated above. If properly trained,

such persons, when they grow up, can use

the limb, which is only a little shorter than the other, and yet they

support themselves on a staff at the affected

side. For, not being able to use properly the ball of the foot without

the heel, nor to put it down as some can

in the other varieties of dislocation (the cause of which has been just

now

stated), on this account they require a

staff. But those who are neglected, and are not in the practice of putting

their foot to the ground, but keep the

limb up, have the bones more atrophied than those who use the limb; and,

at

the articulations, the limb is more maimed

in the direct line than in the other forms of dislocation.

Part 60

On the Articulations

(400 BC)

Aristotle (384-322 BC)

On

the Gait of Animals (350 B.C.)

Questions (part 1)

-

what are the fewest points of motion necessary to animal progression

-

why sanguineous animals have four points and not more, but bloodless animals

more than four

-

why some animals are footless, others bipeds, others quadrupeds, others

polypods

-

why all have an even number of feet

-

why the points on which progression depends are even in number

-

why are man and bird bipeds, but fish footless

-

why do man and bird, though both bipeds, have an opposite curvature of

the legs

Solutions

-

the moving creature always changes its position by pressing against what

lies below it (3)

-

the beginning of movement is on the right: nature of the right is to initiate

movement, that of the left to be moved

-

all men carry burdens on the left shoulder

-

hop easier on the left leg

-

all men lead off with the left

-

men guard themselves with their right

-

spiral-shaped Testaceans have their shells on the right, go forward in

the direction opposite to the spire

-

all animals then start movement from the right

-

the right is more dextrous than the left

-

men and birds are biped because they have the superior part distinguished

from the front (5)

-

animals which have the superior and the front parts identically situated

are four-footed, many-footed, or footless (6)

-

the animal must act with opposite limbs, shifting the weight from the limbs

that are being moved to those at rest (8)

-

without flexion there could not be walking or swimming or flying (9)

-

when then one leg is advanced it becomes the hypotenuse of a right-angled

triangle (10)

-

its square then is equal to the square on the other side together with

the square on the base

-

the one at rest must bend either at the knee

-

If a man were to walk parallel to a wall in sunshine, the line described

(by the shadow of his head) would be not straight but zigzag, becoming

lower as he bends, and higher when he stands and lifts himself up.

-

birds are hunchbacked yet stand on two legs because their weight is set

back (11)

-

their being bipeds and able to stand is above all due to their having the

hip-bone shaped like a thigh

-

one in the leg before the knee-joint, the other joining his part to the

fundament - not a thigh but a hip

-

all creatures which naturally have the power of changing position by the

use of limbs (12)

-

must have one leg stationary with the weight of the body on it

-

and when they move forward the leg which has the leading position must

be unencumbered

-

and the progression continuing the weight must shift and be taken off on

this leading leg

-

it is evidently necessary for the back leg from being bent to become straight

again

-

while the point of movement of the leg thrust forward and its lower part

remain still

-

bird though a biped is not erect, and has the forward parts of the body

lighter than the hind (15)

Archimedes (287-212 BC)

Another Greek, determined hydrostatic principles governing floating

bodies that are still accepted

as swimming. In addition, Heath (1972) suggests that his inquiries

included the laws of leverage and determining the center of

gravity and the foundation of the oretical mechanics.

Galen (131-201 AD)

Roman citizen

who tended the Pergamum's gladiators in Asia Minor and is considered to

have been

Roman citizen

who tended the Pergamum's gladiators in Asia Minor and is considered to

have been

the first team physician in history. He used number to describe muscles.

His essay De Motu Musculorum (On the Movements of Muscles) distinguished

between motor and sensory nerves, agonist and antagonist muscles, described

tonus, and introduced terms such as diarthrosis and synarthrosis. He taught

that muscular contraction resulted from the passage of "animal spirits"

from the brain through the nerves to the muscles. Snook (1978) suggested

that some writers consider his treatise the first textbook on kinesiology,

and he has been termed "the father of sports medicine." Due to his era’s

discouragement of human dissection, the majority of Galen’s work was based

on the dissections of dogs, pigs, and apes.

The

48 cases contained within the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus concern:

The

48 cases contained within the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus concern:

The

scribe of over 3,500 years ago had copied at least eighteen columns of

the venerable treatise and had reached the bottom of a column when, pausing

in the middle of a line, in the middle of a sentence, in the middle of

a word, he laid down his pen and pushed aside forever the great Surgical

Treatise he had been copying, leaving 15½ inches (39 cm.) bare and

unwritten at the end of his roll.

The

scribe of over 3,500 years ago had copied at least eighteen columns of

the venerable treatise and had reached the bottom of a column when, pausing

in the middle of a line, in the middle of a sentence, in the middle of

a word, he laid down his pen and pushed aside forever the great Surgical

Treatise he had been copying, leaving 15½ inches (39 cm.) bare and

unwritten at the end of his roll.

Hippocrates (460-370 BC)

Hippocrates (460-370 BC)

Roman citizen

who tended the Pergamum's gladiators in Asia Minor and is considered to

have been

Roman citizen

who tended the Pergamum's gladiators in Asia Minor and is considered to

have been