|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

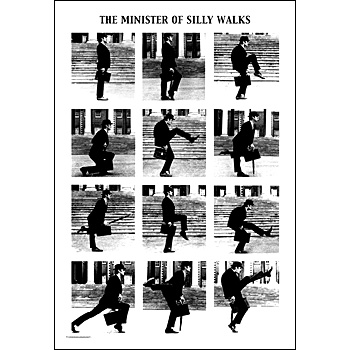

(from Monty Python's Flying Circus episode 14, 1970): Flying Circus theme (344 kB RA stereo)

(from Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl)

(A man dressed in suit complete with bowler hat comes into shop.

He has a silly walk and keeps doing little jumps and then three long paces

without moving the top of his body. He buys a paper, then we follow him

as he leaves the shop.)

(A man dressed in suit complete with bowler hat comes into shop.

He has a silly walk and keeps doing little jumps and then three long paces

without moving the top of his body. He buys a paper, then we follow him

as he leaves the shop.)

Minister: 'Times' please.

Shopkeeper: Oh yes sir, here you are.

Minister: Thank you.

Shopkeeper: Cheers.

(The Minister leaves the shop, from which we see a line of gas men stretching back up the road to Mrs Pinnet,s house (as featured in the New Cooker Sketch), and walks off in an indescribably silly manner. Cut to him proceeding along Whitehall, and into a building labelled 'Ministry of Silly Walks'.)

(Inside the building he passes three other men, each walking in their own eccentric way.)

(Cut to an office; a man is sitting waiting. The minister enters eccentrically.)

Minister: Good morning. I'm sorry to have kept you waiting, but I'm afraid my walk has become rather sillier recently, and so it takes me rather longer to get to work. (sits at desk) Now then, what was it again?

Mr Pudey: Well sir, I have a silly walk and I'd like to obtain a Government grant to help me develop it.

Minister: I see. May I see your silly walk?

Mr Pudey: Yes, certainly, yes.

(He gets up and does a few steps, lifting the bottom part of his left leg sharply at every alternate pace. He stops.)

Minister: That's it, is it?

Mr Pudey: Yes, that's it, yes.

Minister: lt's not particularly silly, is it? I mean, the right leg isn't silly at all and the left leg merely does a forward aerial half turn every alternate step.

Mr Pudey: Yes, but I think that with Government backing I could make it very silly.

Minister: (rising) Mr Pudey, (he walks about behind the desk in a very silly fashion) the very real problem is one of money. I'm afraid that the Ministry of Silly Walks is no longer getting the kind of support it needs. You see there's Defence, Social Security, Health, Housing, Education, Silly Walks ... they're all supposed to get the same. But last year, the Government spent less on the Ministry of Silly Walks than it did on National Defencel Now we get £348,000,000 a year, which is supposed to be spent on all our available products. (he sits down) Coffee?

Mr Pudey: Yes please.

Minister: (pressing intercom) Now Mrs Two-Lumps, would you bring us in two coffees please?

Intercom Voice: Yes, Mr Teabag.

Minister: ... Out of her mind. Now the Japanese have a man who can bend his leg back over his head and back again with every single step. While the Israelis... here's the coffee.

(Enter secretary with tray with two cups on it. She has a particularly jerky silly walk which means that by the time she reaches the minister there is no coffee left in the cups. The minister has a quick look in the cups, and smiles understandingly.)

Minister: Thank you - lovely. (she exits still carrying tray and cups) You're really interested in silly walks, aren't you?

Mr Pudey: Oh rather. Yes.

Minister: Well take a look at this, then.

(He products a projector from beneath his desk already spooled up and plugged in. He fiicks a switch and it beams onto the opposite wall. The film shows a sequence of six old-fashioned silly walkers. The film is old silent-movie type, scratchy, jerky and 8mm quality. All the participants wear 1900's type costume. One has huge shoes with soles a foot thick, one is a woman, one has. very long 'Little Tich' shoes. Cut back to office. The minister hurls the projeaor away. Along with papers and everything else on his desk. He leans foward.)

Minister: Now Mr Pudey. I'm not going to mince words with you. I'm going to offer you a Research Fellowship on the Anglo-French

Mr Pudey: La Marche Futile?

(Cut to two Frenchmen, wearing striped jerseys and berets, standing in a field with a third man who is entirely covered by a sheet.)

First Frenchman: Bonjour ... et maintenant ... comme d'habitude, au sujet du Le Marché Commun. Et maintenant, je vous presente, encore une fois, mon ami, le pouf célèbre, Jean-Brian Zatapathique. (he removes his moustache and sticks it onto the other Frenchman)

Second Frenchman: Merci, mon petit chou-chou Brian Trubshawe. Et maintenant avec les pieds à droite, et les pieds au gauche, et maintenant l'Anglais-Française Marche Futile, et voilà

(They unveil the third man and walk off He is facing to camera left and appears to be dressed as a city gent; then he turns about face and we see on his fight half he is dressed au style franfais. He moves off into the distance in eccentric speeded-up motion.)

How did

it come about?

How did

it come about? Almost

as one man they rushed outside to watch the stranger and his walk but were

too late as the man had already crested the hill and was gone.

Almost

as one man they rushed outside to watch the stranger and his walk but were

too late as the man had already crested the hill and was gone.

Back in Graham's house the two previous conversions continued for some time until, eventually, Terry Jones and Michael Palin came up with the version of the sketch which has become known as The Ministry of Silly Walks and featured John's long legs to good effect.

Some years later, it was revealed how John Cleese came to hate that sketch after many repeated requests for him to "Do the silly walk". The closest he came to repeating it was in "Fawlty Towers", 'The Germans' sketch where he was seen to goose-step around the dining-room.

Basil: "Don't mention the war. I mentioned it once, but I think I got

away with it. So it's all forgotten now and let's hear no more about it.

So that's two egg mayonnaise, a prawn Goebbels, a Herman Goering and four

Colditz salads....no, wait a minute...I got confused because everyone keeps

mentioning the war."

German: "Will you stop mentioning the war?"

Stop

that! - it's silly (4 KB)

![]()

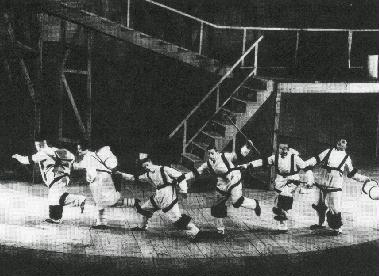

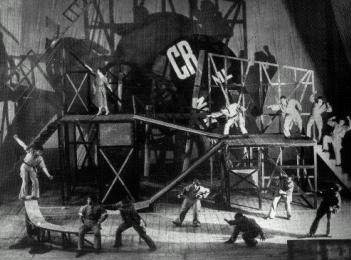

All the World is a Stage and All the Actors are Biomechanists

I was strolling through the halls of academe the other day, really, no kidding, when I noticed a dark, seldom used passageway. Posted above the entrance was, “Art in Motion,” and down the dim corridor, barely illuminated, was a faint notion of staged human movement. Wondering what wisdom waited along this way, I wandered in and witnessed a most unexpected biomechanical phenomenon, Vsevolod Meyerhold’s avant garde Russian theatre of the 1920s.

The Russian revolution was a political upheaval that changed many aspects of Russian life. Along with the political revolution came a revolution in Russian art that continues to influence our society’s aesthetic, architectural and design sensibilities. Vsevolod Meyerhold (1874-1940) was the leader of the New Theatre in Russia after the revolution and biomechanics was the central tenet to Meyerhold’s philosophy. Meyerhold sought to develop the, “new actor,” using human movement as the basis of theatrical expression. Through exquisite control of one's body, the actor could precisely express any particular emotion or thought. Meyerhold envisioned the biomechanical actor with,

Man at last will begin to harmonize himself in earnest. He will make his business to achieve beauty by giving the movement of his own limbs the utmost precision, purposefulness and economy....Movement is the most powerful means of theatrical expression...(and it) is more important than any other theatrical element....Since the art of the actor is the art of plastic forms in space, he must study the mechanics of his body. This is essential because any manifestations of a force, including the living organism, is subject to constant laws of mechanics and obviously the creation by the actor of plastic forms in space is a manifestation of the force of the human organism.

Meyerhold formulated his system from the work of western, industrial visionaries Frederick W. Taylor and Frank and Lillian Gilbreath, the cultural revolution in Russia, and the physiology giant Ivan Pavlov. Taylor and the Gilbreaths revolutionized industrial production in the 19th and early 20th centuries with motion and time studies. These early ergonomists delineated efficient, functional movements for laborers to increase productivity. Efficient human movement was part of the broader sociological philosophy of man-as-machine, a by-product of the Industrial Revolution and the current, seminal applications of mechanics to human movement. Constructivists, revolutionary artists contributing to the new utopian state, called for the end of ornamental art and the birth of utilitarian art, the art of production, the art of function. Meyerhold synthesized the ideas of efficient movement in his actors and utilitarian art in set and costume design into his revolutionary theatrical system of biomechanics. Efficient actor movement was optimized in the utilitarian, constructivist environment. Meyerhold’s theatre symbolized man’s functional role in industrial Soviet society, society’s tool for production, man-the-living-machine. The photograph from, “The Magnanimous Cuckold,” (1921) shows biomechanically trained actors in Liubov Popova’s constructivist set design emphasizing production materials and function over aesthetics.

Pavlov developed the concept of reflexology, a conditioned response to a stimulus. Meyerhold used this idea in his biomechanical training to bring the actor to a, “point of excitability,” so that a theatrical stimulus would elicit a reflexive movement response in the actor. According to Meyerhold, “The biomechanical system of acting, starting from a series of devices designed to develop the ability to control one’s body within the stage space in the most advantageous manner, leads one to the most complex questions of acting technique, problems concerning the coordination of movement, words, the capacity to control one’s emotions, one’s excitability in performance. The emotional state of the actor, his temperament, his excitability, the emotional sympathy between the actor as artist and the imaginative process of the character he is performing - all of these are fundamental elements in the complex system of biomechanics.”

Meyerhold developed his methods during the first two decades of this century and he brought the system to fruition at the Meyerhold Workshop in 1921. The Workshop was Meyerhold’s school for training biomechanical actors and the curriculum included theoretical and applied course work comparable to our modern, scientific training. Meyerhold taught courses in biomechanics that included lectures on functional anatomy of the upper and lower extremities and the trunk, motor action of the human body and stimulation of muscle, balance and the body center of gravity, the human organism as an automotive mechanism and the mechanism of reaction in the nervous system. The applied course work included movement-based classes in which the actor learned and practiced numerous gymnastic-like actions or, “etudes,” to hone his or her physical skills. All of these courses were taught in the Laboratory of Biomechanics, probably the first laboratory so named. As biomechanics laboratories have today, Meyerhold’s Laboratory had research assistants, the most notable being Sergi Eisentein, the future film director. Vsevolod Meyerhold and his research assistants created a biomechanical niche in the world of theatre that explored the artistry and expressiveness of efficient human movement. Their work continues today in our laboratories as we explore the science and effectiveness of the same movements.

Who knew?

Paul Devita

Biomechanics Laboratory

East Carolina University

The author gratefully acknowledges Lisa DeVita’s and Tibor Hortobagyi's editorial assistance and Mary Flesher’s contributions toward identifying the origin of the word, “biomechanics.” Unfortunately, I could not identify its origin by press time. I therefore ask the reader, who invented the word, “biomechanics,” and when did this occur?

She hummed the "Marseillaise" as she was wheeled down the hospital corridor and afterwards used a wheelchair, disdaining prostheses and crutches - bearers instead carried the divine Sarah around in a specially designed litter chair in Louis XV style with gilt carving, like a Byzantine princess. Immediately upon leaving the hospital, she filmed Jeanne Dore (1915), again directed by Louis Mercanton. She was shot either standing or sitting; this in fact pinned her down and forced her to use facial expression rather than movement and helped her performance. The five-reel film, distributed by Universal in the U.S., got rave reviews and reflected well upon both its game star and the industry as an art form. For ovations she stood on one leg, held on to a piece of furniture, and gestured with one arm.

Shortly after the amputation, she visited the WWI front lines near Verdun to perform for French troops in mess tents, hospital wards, open market places and ramshackle barns. Propped in a shabby armchair, she recited a patriotic piece to war-dazed men fresh from the trenches. When she ended with a rousing “Aux armes!” they rose cheering and sobbing. “The way she ignored her handicap was beautiful,” wrote an actress who accompanied her. “A victory of the spirit over the failing flesh.”

Her final tour through America lasted from 1916 to 1918 and then she returned home to France. Bernhardt continued to practice her craft until her death in 1923. She was made a member of France's Legion of Honour in 1914.

Richard Gordon: An Alarming History of Famous and Difficult Patients:

Amusing Medical Anecdotes from Typhoid Mary to FDR. St. Martin's Press;

(1997)

Spy phone built into secret agent Maxwell Smart's left shoe on the espionage

comedy GET SMART (1965-70). His shoe phone number was 306. When he dialed

the number 117, his shoe would convert into a gun. Max's shoes also contained

deadly weaponry. Housed in a small compartment of his left heel were two

pellets-the small one explodes when thrown or heated; the larger one was

a suicide pill which killed painlessly in twenty seconds when swallowed.

In the movie spin-off 'The Nude Bomb', a.k.a. 'The Return of Maxwell Smart'

(1980), the shoe phones were updated to include touch-tone dialing and

an answering machine.

Robert Wyatt

is the only person to play on the long-runnng British TV show Top of the

Pops in a wheelchair. Drummer for '60s psychedelic outfit, The Soft Machine

'66--71 In June 1973, drunk at a party, Wyatt fell from a fourth floor

window, breaking his back. He emerged as a full-time wheelchair user.

Robert Wyatt

is the only person to play on the long-runnng British TV show Top of the

Pops in a wheelchair. Drummer for '60s psychedelic outfit, The Soft Machine

'66--71 In June 1973, drunk at a party, Wyatt fell from a fourth floor

window, breaking his back. He emerged as a full-time wheelchair user.

Did the accident change his perspective on life? "No," he says. "It was just like falling off a bicycle. I just fell off and got back on from another angle, really.

"It was a sort of bizarre diversion... a bit like a very long dream.

When you wake up, you're disorientated and you can't quite remember the

story. And you think:

'Oh, no, that was part of the dream'. To that extent, it was quite

disorientating, but not unpleasantly so."

"I didn't feel sorry for myself, I just felt sorry for Alfie, really.

We'd only been together for a couple of years when it happened, and suddenly

she had a paraplegic

husband in a wheelchair. She learned to drive because she realised

I wasn't going to be getting on and off buses and trains.

"I'd written a lot of Rock Bottom just before the accident," Wyatt recalls.

"I can't really write music properly, so all I remember was going through

things over and

over in my head so I wouldn't forget them. In hospital, you don't have

to worry about the rent or where the next meal is coming from. So I was

able to think about

music month after month while I was fed and watered. I found an unused

room in the hospital with a little upright piano in it. The alternative

to hiding in that room

was being taken off to do archery or wholesome exercises."

So he never got bitten by the archery bug, then? "No, it never really

got to me," he laughs. "The archery teacher was a funny bloke: very odd.

He used to come up

to you and say: 'I used to work for the LA Police, you know. I don't

have to be doing this.' I'd say: 'Right. OK'. We weren't drawn to each

other, so archery didn't

really take off."

After Rock Bottom came Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard, which included the first of his two hit singles, an idiosyncratic take on The Monkees' I'm A Believer.

Has he ever felt discriminated against within the music business? "I've only been discriminated against once when I first went on Top Of The Pops with his surprise top 30 UK hit '74 with cover of Monkees' 'I'm A Believer'. This guy was obviously very embarrassed that I was in a wheelchair and didn't feel it was right for the show. Because nobody had said that to me before, I was completely thrown and I swore at him. Then he said: 'You'll never work on this programme again.' Thus 'Shipbuilding' '83 (reached UK top 40; by Elvis Costello was not aired.

"And he was dead right about that," he chuckles.

Series 1, episode 3. First aired 23 July 2001

Hugh

Laurie wouldn't seem like the first choice to play an ill-mannered American

medical genius. Laurie says he's still learning the nature of the complex

and contradictory House, whose medical mastery is countered by life challenges,

including a leg disability, a reliance on painkillers and seemingly non-existent

social skills. He admires House for not worrying about what others think

of him.

Hugh

Laurie wouldn't seem like the first choice to play an ill-mannered American

medical genius. Laurie says he's still learning the nature of the complex

and contradictory House, whose medical mastery is countered by life challenges,

including a leg disability, a reliance on painkillers and seemingly non-existent

social skills. He admires House for not worrying about what others think

of him.

"It's a wonderfully liberating thing. I wish I could be more like that," he says. "I think all actors care (what others think). They want to be loved. They want applause. It's pathetic, but here it is."

"One of the things that makes me feel guilty about playing this role is that my dad was a doctor," Laurie says. "He was a very gentle soul and, I think, a very good doctor. And I'm probably being paid more to become a fake version of my own father."

Laurie, 45, says he's fascinated by the character of Gregory House, an infectious-disease specialist at a New Jersey hospital who brutalizes colleagues and patients with his harsh honesty. But he likes House — he'd have him as his doctor — and applauds Fox for taking a chance on an unconventional lead who chooses intellect over empathy. "The boldest thing they've done is put such a mean, unsympathetic character at the center of it," says Laurie.

In the first episode Laurie says that his limp and pain is due to a misdiagnosed thigh muscle infarction: "not many people have felt the pain of dying muscle".