The pioneering "one small step" taken by Neil A Armstrong (38): picture via television by Apollo lunar surface camera, black bar through center of picture is anomaly in the Goldstone ground data system (NASA photo ID S69-42583)

The pioneering "one small step" taken by Neil A Armstrong (38): picture

via television by Apollo lunar surface camera, black bar through center

of picture is anomaly in the Goldstone ground data system (NASA photo ID

S69-42583)

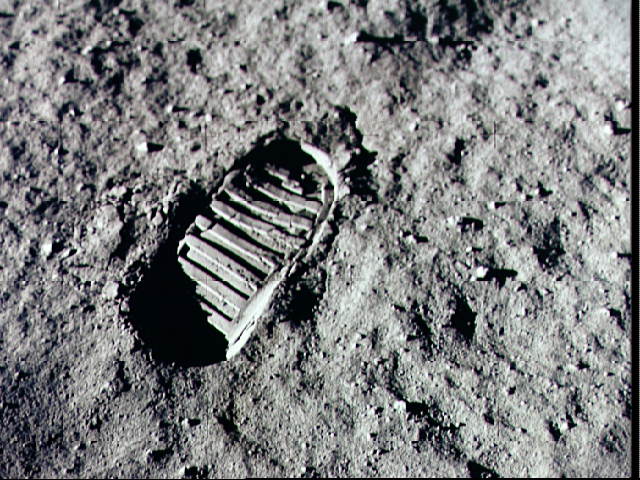

Armstrong's first footprint (70mm lens). The prints left by the astronauts in the Sea of Tranquility are more permanent than many solid structures on Earth. Barring a chance meteorite impact, these impressions in the lunar soil will probably last for millions of years. The impression, about 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) deep, demonstrates the fineness and cohesiveness of the lunar soil. (NASA photo ID AS11-40-5877&78)

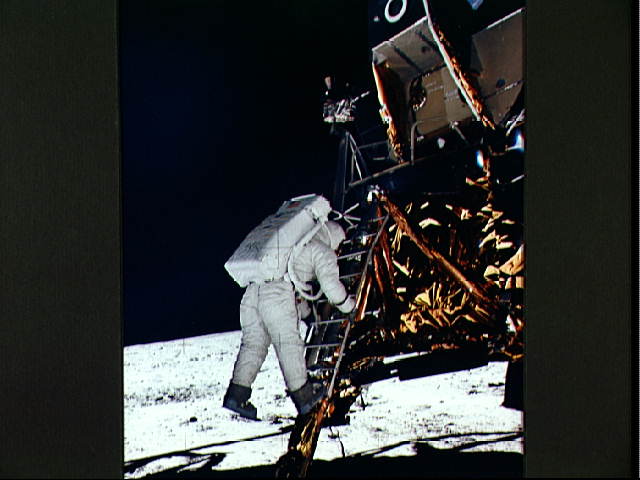

Edwin E. "Buzz" Aldrin (39) joined Armstrong on the surface less than

fifteen minutes later, in this photo taken by Armstrong. As he left the

LM, Aldrin said, "Now I want to partially close the hatch, making sure

not to lock it on my way out." "A good thought." replied Armstrong (NASA

photo ID AS11-40-5868)

Buzz Aldrin's first footprint

More moonwalk audio & video

The EVA was recorded by a TV camera mounted on the reserve retrorocket

assembly and a film camera mounted on the airlock. The suit was very cumbersome,

and Leonov experienced a disorienting euphoria while outside of the vehicle.

The automatic reentry system failed and they were forced to make a manual

descent. The capsule missed the scheduled landing zone by some hundred

kilometers, creating a delay of 24 hours before the crew were reached.

Written by Liam Sternberg

Written by Liam Sternberg

Walking Men Green

(Oil on canvas 1963 80.00 x 60.00 Inches)

Walking Men Green

(Oil on canvas 1963 80.00 x 60.00 Inches)

Walking man, Wilderness

Body Painting

Walking man, Wilderness

Body Painting

Self-Portrait

as Rodin's Walking Man, with Appendages

Self-Portrait

as Rodin's Walking Man, with Appendages

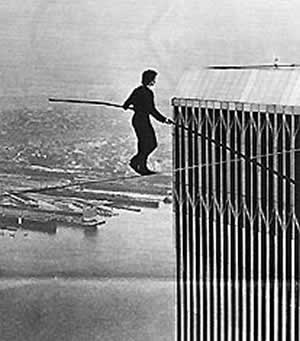

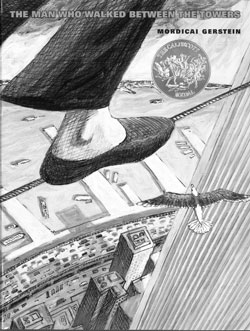

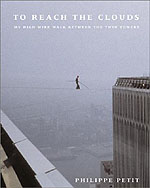

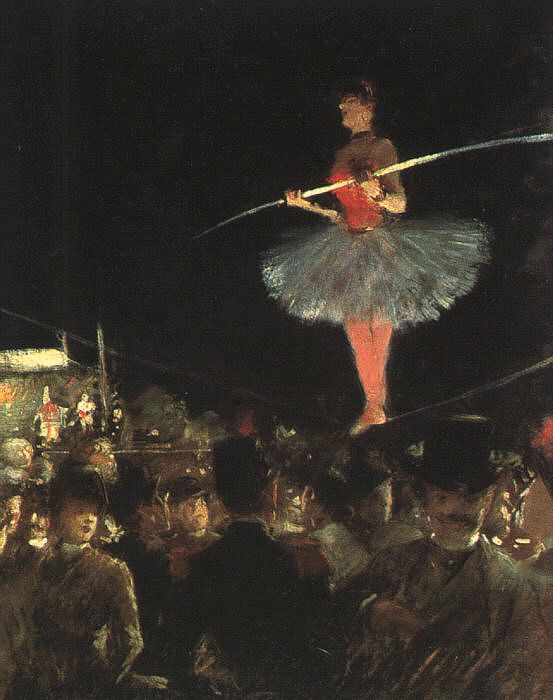

"The

Man Who Walked Between the Towers,?is about the tightrope artist, Philippe

Petit. In 1974, before the World Trade Center was completed, Petit was

a young daredevil who had walked between the steeples of Notre Dame Cathedral

in Paris. Walking between the Trade Center towers would be a little more

complicated, and slightly illegal. But Petit was undeterred. He snuck into

the towers with some friends, dressed as construction workers. Late at

night, they strung the 440-pound reel of cable, which was only 5/8th of

an inch thick, across the towers. They used a bow and arrow to shoot a

leader line across the gap. After dawn, he took his 28-foot balancing pole

and started walking across the wire, feeling happy, free and unafraid.

It didn’t take long before a crowd appeared and the police shouted with

bullhorns for him to get down. But Petit walked, ran, danced, skipped and

even lay down on the wire for almost an hour before he walked back to the

towers and was arrested. The judge was lenient ?he ordered Petit to perform

for some children in a New York City park. Ironically, during one of these

performances, Petit fell when some boys jerked on the wire. But he caught

himself.

"The

Man Who Walked Between the Towers,?is about the tightrope artist, Philippe

Petit. In 1974, before the World Trade Center was completed, Petit was

a young daredevil who had walked between the steeples of Notre Dame Cathedral

in Paris. Walking between the Trade Center towers would be a little more

complicated, and slightly illegal. But Petit was undeterred. He snuck into

the towers with some friends, dressed as construction workers. Late at

night, they strung the 440-pound reel of cable, which was only 5/8th of

an inch thick, across the towers. They used a bow and arrow to shoot a

leader line across the gap. After dawn, he took his 28-foot balancing pole

and started walking across the wire, feeling happy, free and unafraid.

It didn’t take long before a crowd appeared and the police shouted with

bullhorns for him to get down. But Petit walked, ran, danced, skipped and

even lay down on the wire for almost an hour before he walked back to the

towers and was arrested. The judge was lenient ?he ordered Petit to perform

for some children in a New York City park. Ironically, during one of these

performances, Petit fell when some boys jerked on the wire. But he caught

himself.

Walking Man (On the Edge), 1995 fiberglass and steel 72 x 60 x 24 inches

Location: Roof of Commons Building Johnson County Community College

Walking Man (On the Edge), 1995 fiberglass and steel 72 x 60 x 24 inches

Location: Roof of Commons Building Johnson County Community College

Walking on Two Balls,

1995

Walking on Two Balls,

1995

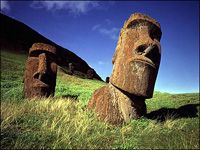

Moai on the slope of Rano Raraku (click for video)

Moai on the slope of Rano Raraku (click for video)

Walking

Kung :breathing for health

Walking

Kung :breathing for health

Walking

(60 x 80cm).

Walking

(60 x 80cm).

The Tightrope Walker, Acrylic on canvas, 42" x 60" © 1993

The Tightrope Walker, Acrylic on canvas, 42" x 60" © 1993

The Tightrope Walker

The Tightrope Walker

Tightrope Walker, Piece #: 11402-20

Tightrope Walker, Piece #: 11402-20

Walking in the Rain

Walking in the Rain

Walking in the Rain,

24" x 36", Oil on canvas

Walking in the Rain,

24" x 36", Oil on canvas

Walking with

God, 23" x 13 7/8" (2000)

Walking with

God, 23" x 13 7/8" (2000)

"X-ray style" figure,Rock painting, ca. 6000 B.C.E., Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia

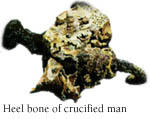

On early crucifixes four nails were used to crucify Jesus. During the medieval period (in the 15th century) this number was changed to three in honor of the Holy Trinity especially when the nails were painted apart from the cross as symbols of the Passion. When three nails are used, a single nail pierces both of the victim's feet. Fr. James Groenings, S.J. in the Passion of Jesus and Its Hidden Meaning claims that four nail holes were discovered on the True Cross and that the stigmata of St. Francis reflected the use of four nails during the crucifixion of Christ. Because of the shape of their dried buds, clove flowers are symbols of the Holy Nails. "Clove" comes from the Latin "clavus" meaning "nail."

The

legs were pressed together, bent, and twisted to that the calves were parallel

to the patibulum. The feet were secured to the cross by one iron nail driven

simultaneously through both heels (tuber calcanei) with the right foot

above the left. the

The

legs were pressed together, bent, and twisted to that the calves were parallel

to the patibulum. The feet were secured to the cross by one iron nail driven

simultaneously through both heels (tuber calcanei) with the right foot

above the left. the

legs would be flexed at a 45 degree angle and the feet were flexed

downward at a 45 degree angle until they were parallel to the vertical

beam. The feet would be driven through with another spike between the 2nd

and 3rd metatarsal bones. The dorsal pedal artery would be severed and

again the nerve would be pierced or pressured and the Tarsal bones would

act as the brake for keeping the spike from ripping through the foot as

the victim pushed against it.

The condemned man could buy time by pushing himself up on the nails

in his feet, stretching his legs and so raising the body to relieve the

chest and arms. This allowed his to breathe better - for a while. But perching

with a full weight of the body on a square nail driven through the middle

bones of the feet brings intolerable pain. The victim soon lets his knees

sag until once more he is hanging from the wrists, with the median nerves

again strung over the nail shafts. The cycle is repeated to the limit of

endurance.

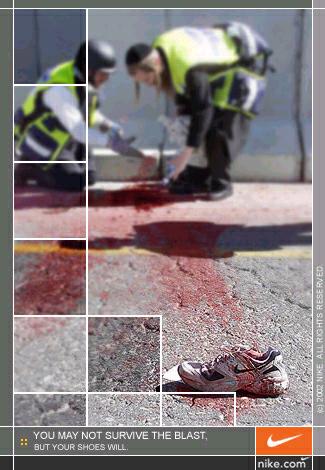

A massive bomb rocked the Pacific resort island of Bali on October 12, 2002, destroying a night club in Kuti, killing nearly 200 people and injuring scores of others from countries all over the world.

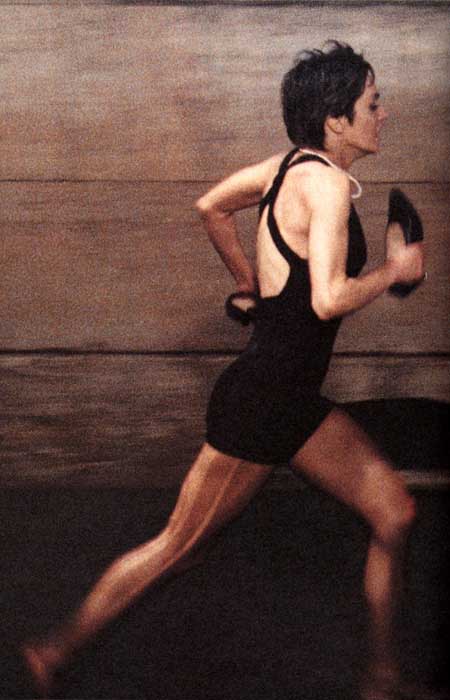

Nike

is no stranger to controversy when it comes to advertising. In September

2000, a barrage of complaints from viewers prompted NBC to drop a Nike

commercial which featured U.S. Olympic runner Suzy Favor Hamilton outrunning

a chainsaw-wielding man in a hockey mask. (The ad ended with the attacker

collapsing in exhaustion while Ms. Hamilton sped off, leading to the caption:

"Why sport? You'll live longer."). Although Nike intended the commercial

to be a parody of the slasher/horror film genre, thousands of TV viewers

complained that the ad could be construed as advocating violence towards

women.

Nike

is no stranger to controversy when it comes to advertising. In September

2000, a barrage of complaints from viewers prompted NBC to drop a Nike

commercial which featured U.S. Olympic runner Suzy Favor Hamilton outrunning

a chainsaw-wielding man in a hockey mask. (The ad ended with the attacker

collapsing in exhaustion while Ms. Hamilton sped off, leading to the caption:

"Why sport? You'll live longer."). Although Nike intended the commercial

to be a parody of the slasher/horror film genre, thousands of TV viewers

complained that the ad could be construed as advocating violence towards

women.

One month later, Nike pulled a print advertising campaign for their ACG Air Dri-Goat trail running shoes from various outdoor and backpacking-related magazines after another round of complaints from readers who found the ad copy (which made reference to a "drooling, misshapen, non-extreme-trail-running" non-Nike wearer now "forced to roam the Earth in a motorized wheelchair") to be unfunny and insulting to the disabled.

Despite these previous public relations gaffes, Nike hasn't stooped

so low as to try to sell shoes with advertisements employing terrorist-related

imagery. The image shown above; showing a bloodied Nike shoe in the foreground

and security forces investigating what is presumably the aftermath of a

suicide bombing in the background, all over a caption reading "You may

not survive the blast, but your shoes will"; is not a real Nike ad.

This offensive ad was not authorized by Nike and has no affiliation with

the company. It was

obviously created by some individual who does not value human life and

is seeking attention by

leveraging our well-known brand name.

Based upon the number of inquiries we have received from members of the

public questioning

the ad's authenticity, we have begun to work with authorities to try to

determine the origin.

Also, we have begun to contact specific non-governmental organizations

to apprise them of

this unfortunate hoax.

Again, Nike was never involved in any way with the ad and appreciates your

inquiry. If you

have any information regarding individuals or businesses improperly promoting

this image as a

Nike property, please contact us so that we may explore appropriate legal

recourse. We also

ask that you limit circulation of this despicable image and share this

message with others

who inquire about its authenticity or affiliation with Nike.

We hope this clarifies the matter.

I was in a bar (as one frequently is) at the end of a day's labors. There

were televisions lit up, one on

the left, another on the right, with pictures from statue-strewn Baghdad

streets. And just then the

barmaid across from me, clearly thirsting as much for information on another

culture as I was for a

Scotch, asked aloud, and quizzically: "What's with the shoes?!"

How can one not have noticed, and wondered about, the shoes?

In recent days we've seen Baghdadis, Basrans, Kirkukis, Karbalites, Dearbornis--Iraqis

of all

sorts--assaulting every fallen statue of Saddam Hussein, every unseated

portrait of the tyrant, with

their footwear. We've seen leather shoes, plastic sandals, rubber flip-flops,

even (or was this an

illusion?) some Nikes, long-laced and incongruous. Everything but stiletto

heels, which aren't, if I may

be permitted a rare generalization, big in the Arab world, at least not

in public.

These images--these flailings of sole against statuary--have been among

the most charming of any to

emerge from Freed Iraq, and arguably the most intriguing to Western viewers.

One can comprehend

the toppling of the totemic figures in town squares, and one has, in fact,

seen this sort of thing

before: in Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Romania and other places at the end

of the Cold War. But one

never saw men in Vilnius, Cracow, Minsk or Timisoara flay their bronze

or plaster Lenins and

Ceaucescus with their shoes. There may have been some kicking, but no one

in the East Bloc ever

discalced himself to hand-deliver a thrashing to a crippled icon.

So what is it with the shoes in Iraq?

As anyone who has been to the Middle East (or even to countries like India)

knows, the foot and shoe

are imbued with considerable significance.

The foot occupies the lowest rung in the bodily hierarchy and the shoe,

in addition to being something

in which the foot is placed, is in constant contact with dirt, soil and

worse. The sole of the shoe is the

most unclean part of an unclean object. In northern India, where I grew

up, the exhortation "Jooté

maro!" ("Hit him with shoes!") was invoked when one sought to administer

the most demeaning

punishment. (Another footwear tidbit: The effigies of unpopular politicians

in India are regularly

garlanded with shoes and paraded down the streets.)

In the Muslim world, according to Hume Horan, a former U.S. ambassador

to Saudi Arabia, "to have the

sole of the shoe directed toward one is pretty much the equivalent of someone

in our culture giving

you the finger." Matthew Gordon, a historian of Islam, says that since

one takes one's shoes off before

entering a mosque--as a way of maintaining the purity of the place of worship--"the

use of a shoe as

something to hit you with is an inversion, directing impurity and pollution

at the object of the beating."

The fact that the shoe-as-anathema idea stretches across the Arab world

into India suggests that

the cultural aversions (and the attendant insults) predate Islam and may

have had their origins in a

poorly understood--but basically correct--connection between dirt (i.e.,

pollution) and footwear. In

societies where levels of public hygiene are low (e.g., much of the Middle

East and the Indian

Subcontinent), it is still commonplace to remove one's shoes before entering

a private home, and not

just places of worship. Which begs the question, of course, of why shoes

weren't so removed in

medieval Europe, whose streets were just as dung-flecked, or are not so

removed in present-day,

non-Muslim Africa.

But the fact remains that Iraqis today are deriving sumptuous pleasure--part

ritual, part

catharsis--from their chance to hit Saddam with the soles of their shoes.

In this, they are not merely

degrading him but also exacting retribution for bastinadoes suffered in

the past. There probably isn't a

single non-Baath-Party Iraqi who wasn't personally beaten or knocked about

by the authorities--or

who doesn't know someone so ill-used.

Ultimately, there could also be a practical explanation for "the shoes."

It may well be that in

impoverished Iraq, nobody except those in the military could afford decent

footwear. So kick the

bronze head too hard and you hurt your own foot. Better, and safer, to

take the shoe off and go

thwack, thwack, thwack, thwack.

Mr. Varadarajan is editorial features editor of The Wall Street Journal.

Five brothers and sisters who can

walk naturally only on all fours are being hailed as a unique insight into

human evolution after being found in a remote corner of rural Turkey. Scientists

believe the family may provide information on how man evolved from a four-legged

hominid to develop the ability to walk on two feet more than three million

years ago. A genetic abnormality that may prevent the siblings, aged from

18 to 34, from walking upright, has been identified.

Five brothers and sisters who can

walk naturally only on all fours are being hailed as a unique insight into

human evolution after being found in a remote corner of rural Turkey. Scientists

believe the family may provide information on how man evolved from a four-legged

hominid to develop the ability to walk on two feet more than three million

years ago. A genetic abnormality that may prevent the siblings, aged from

18 to 34, from walking upright, has been identified.

The discovery of the Kurdish family in southern Turkey in July 2005 has triggered a fierce debate. Two daughters and a son have only ever walked on two palms and two feet, with their legs extended, while another daughter and son occasionally manage a form of two-footed walking. The five can stand up, but only for a short time, with both knees and head flexed. Some researchers claim that genetic faults have caused the siblings to regress in a form of "backward evolution". Other scientists argue more strongly that their genes have triggered brain damage that has allowed them to develop the unique form of movement.

But all agree that the family's walk, described as a "bear crawl", may offer invaluable information on how our apelike ancestors moved. Rather than walking on their knuckles like gorillas and chimpanzees, the family are "wrist walkers", using their palms like heels with their fingers angled up from the ground. Scientists believe this may be the way hominids moved, allowing them to protect their fingers for the more delicate and dextrous manoeuvres so critical in the evolution of man. Nicholas Humphrey, evolutionary psychologist at the London School of Economics, who has visited the family, said the siblings appeared to have reverted to an instinctive form of behaviour encoded deep in the brain, but abandoned in the course of evolution. "It has produced an extraordinary window on our past," he said. "It is physically possible, which no one would have guessed from the (modern) human skeleton." Professor Humphrey, who has been contributing to a BBC program, The Family that Walks on All Fours, broadcast on March 17 2006, said that weeks of study, and factors such as the shape of their hands and the callouses on them, showed this was a long-term pattern of behaviour and not a hoax.

The siblings, who live with their parents and 13 other brothers and sisters, are mentally retarded as a result of a form of cerebellar ataxia. Their mother and father, who are themselves closely related, are believed to have passed down a unique combination of genes resulting in the behaviour. Professor Humphrey said cultural influences in their upbringing might have played a crucial role, with parental tolerance allowing the children to keep to quadrupedal walking. But others believe the cause is more purely genetic.

Uner Tan, a professor of physiology at Cukurova University in Adana,

Turkey, who first brought the family to the attention of scientists, argues

that the gene mutations have made them regress to a "missing link" primate

state. Researchers said that while the women affected - Safiye, 34, Senem,

22, and Amosh, 18 - tended to spend their time sitting outside the family's

very basic rural home, one brother, Huseyin, 28, went into the local village

on all fours, where he could engage in the most basic interactions. Jemima

Harrison, of Passionate Productions, which produced the documentary, said

the family's identity and location were not being disclosed. "They walk

like animals and that's very disturbing at first," she said. "But we were

also very moved by this family's tremendous warmth and humanity."

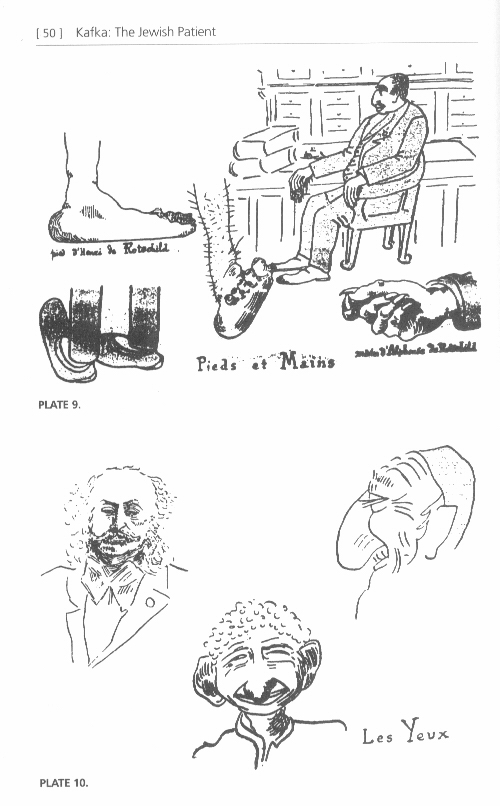

from Franz

Kafka: The Jewish Patient, by Sander Gilman

from Franz

Kafka: The Jewish Patient, by Sander Gilman

Gilman offers an explanation for the anomaly of Kafka's intense sense of his own Jewishness, expressed in his correspondence and diaries and confirmed by virtually all his biographers, in contrast to the almost total lack of explicit references to Judaism, Jews, or Jewishness in his "literary" texts. The Jewishness which he saw in his father's body, and which he felt to be inscribed on his own, marked him as ineradicably different, even diseased.

Amongst other physical markers, such as tuberculosis, stooped posture, deafness and pigeon-toeing, flat feet were believed to be a sign of Jewishness.

It almost goes without saying that there is no evidence to support such

ideas.

When the dear God made the Jew, he made him,

like Adam, out of damp clay. Then he told him to remain lying in the sun

to dry. But since from the

beginning the Jew has shunned the light and

been drawn to the darkness, he disobeyed the command of the true God and

rose prematurely. Since the

clay was still damp and soft, the know-all

developed not only bandy legs but also flat feet after the first few steps.

When the Creator saw this

disobedience of his first creation, he grew

angry and hurled a meteor at the runaway, which knocked him flat on his

face. The Jew got up. Now the sign

was on his face as well. No wonder that he

still flees today and tries to revenge himself by godlessness? (Hofmann

n.d., repr. in Gilman 1991, 46; my

translation)

The Jew is here represented in terms not just of the collapse of uprightness, but in terms of an interchange of the intellectual and physical portions of the body. As a punishment for his disobedience, and his abhorrence of the light, the Jew is made to bear the mark of his prostration on his face, as well as in his flat feet and sagging legs; his flattened nose must here be understood as a grotesque transformation of the face into a kind of foot.

This association of the Jew with the incapacity to retain an upright

posture is dramatised fully in Oskar Panizza's nauseating fable `The Operated

Jew' of 1893. The

Jew who is the subject of this story, Itzig Faitel Stern, walks with

a posture that threatens collapse at every point. Implicit here is an ideal

model of walking as a

cooperation of earth and sky, in which man is the principle of uprightness

which connects the two dimensions. Stern's manner of walking is a dramatisation

of the

failure of uprightness, which extends all the way up to Itzig's head

which must be firmly braced to prevent it sinking to the earth:

When he walked, Itzig always raised both

thighs almost to his midriff so that he bore some resemblance to a stork.

At the same time, he lowered his

head deeply into his breast-plated tie

and stared at the ground. One had to assume that he could not gauge the

strength needed for lifting his legs as he went head over heels...When

I asked him one time why he moved so extravagantly, he said, `So I can

moof ahead!' ?Faitel also had trouble keeping his balance, and when he

walked, there were often beads of sweat streaming from the curly locks

of hair around his temple. The collar wrapped around my friend's neck

was fastened tightly and firmly. I assume that this was due to the difficulty

and work Itzig needed to keep his head pointed upright toward God's heavens.

In its natural position, Itzig's head was always pointed toward earth,

the chin drilled solidly into the silk breast-plated tie. (Panizza 1991,

49)

Gilman's evidence makes it clear that the Jew is subject to strikingly

contradictory explanations for his impaired gait. On the one hand, it is

the mark of his incapacity

for higher mental functions, and failure of spiritual awareness (the

Jew ends up, like Lucifer, crawling on his belly, because he turns away

from the light). But the

physical incapacity of the Jew is also explained by his hypertrophied

mental functions; for the Jew is said to be neurasthenic, hysterical, out

of touch with his natural

being. So the weakness of the Jew's feet is the mark both corporeality

and intellectualism, of baseness and over-refinement, earthliness and ethereality.

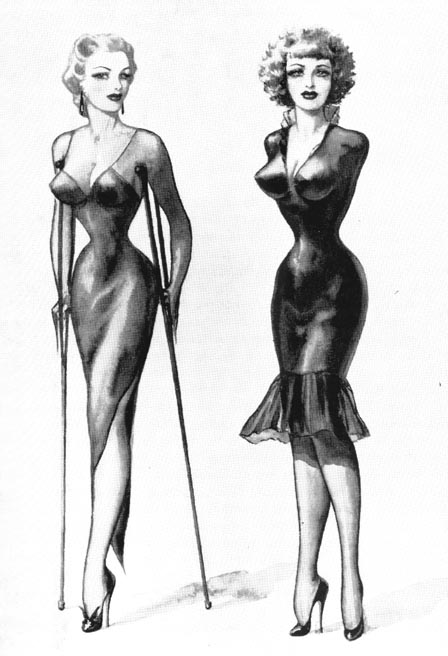

Klaus Theweleit's investigations (1987) of the psychopathology of fascist

representations of the body suggest a further role for the foot. Theweleit

argues that, in

Nazi fantasy, the male body must be preserved intact against all the

forms of threatening, engulfing fluidity identified as female degeneration.

This preservation can

involve the ideal either of continence or of transcendence; either

the control of a turbulent bodily interior of formless flows by a fiercely

constrictive exterior, or the

rigidity, detachment and verticality of the erect penis, which stands

clear of the threatening swamp of indistinction. The strict, but inadequate

corsetry provided by

Stern's collar in the passage from `The Operated Jew' just quoted appears

to be a conflation of these two modes.

Although Theweleit has no explicit discussion of the foot, it clearly

has a vital importance in the symbolic conversion of earth into air, of

what lies basely underfoot

into what resists engulfment. In homo erectus, after all, the foot

is the only part of the body the natural condition of which is horizontal,

redoubling the flatness of the ground against which erection, in all of

its senses, sexual, architectural, spiritual and so on, is defined. The

ideal, integrated, vertical body of the Western imagination holds out through

its feet against a feared collapse into the condition of the foot. As Richard

M. Griffith has put it, in the course of a rhapsodic attempt to reinstate

the phenomenological dignity of the foot:

The ground is not only what I take my stand

on (the underground of me) but the background against which as human I

may be perceived the most

sharply. I am earth: from dust becometh, to

dust returneth. But only against the earth, in opposition to it, do I exist

as human. I must maintain my

separation from the earth. (Griffith 1970,277)

Itzig Faitel Stern's crazy disequilibrium, which becomes an actual collapse

at the end of `The Operated Jew', when his carefully constructed Aryan

body and manner

fall apart under the influence of alcohol at his wedding, betrays the

nature of a body which fails sufficiently to distinguish itself from the

earth, fails, in the

Heideggerean reading of the etymology of the word, to ex-ist, to stand

out or stand forth, to `build' where it `dwells'. Stern's is therefore

another body which is

written through by the foot. The story ends with a grotesque reversion

of Stern's synthesised Aryan body to an Asiatic or Semitic formlessness,

precipitated at the

point at which Stern has become nothing more than the autonomous uncontrolled

motion of his feet:

Everyone looked with dread at the crazy, circular

motions of the Jew. The ignominious fate, which is the fate of all drunkards,

befell Faitel, too. A

terrible smell spread in the room, forcing

those people who were still hesitating at the exit, to flee while holding

their noses. Only Klotz remained behind.

And finally, when even the feet of the drunkard

were too tired to continue their movements, Klotz's work of art lay before

him crumpled and quivering,

a convoluted Asiatic image in wedding dress,

a counterfeit of human flesh, Itzig Faitel Stern. (Panizza 1991, 74)

If the foot has a kind of theological function in terms of the vertical

reading of the body and its postures, then it also has a geopolitical significance.

Modernity is

associated on the one hand with the establishment of nations, the assertion

of a range of ways of belonging to particular places and spaces; on the

other, of course, a

systematic territorial and political displacement also began to be

a defining experience of modernity, with the increased movement of peoples

across national

boundaries, facilitated both by technology and the artifices of civilisation,

and, increasingly during the twentieth century, by the effects of war.

For the nineteenth

century, Sander Gilman suggests, the form of the Jewish foot is the

mark of the effect of modern civilisation, and especially city life, since

`the Jew is both the city

dweller par excellence as well as the most evident victim of the city'

(1991, 49). The metropolitan foot is a foot that has no traditional relation

to the ground it treads.

The revulsion against the alienations of city life had its left-wing

pastoralist forms in the 1920s as well as its more well-known right-wing

forms in the fascist

promotion of the authentic relation between the people and the earth

underfoot; the Jew was defined as the creature and embodiment of modernity

because of a lack

of grounding, condemned to wander over the surface of the earth without

ever being able to establish a relation to any one portion of it. The abjectness

of the foot

will prove to have a significant relationship to its modern rootlessness.

But this absence of sustained attention to the foot as psychoanalytic

subject in the work of Freud contrasts with a remarkably strong metaphorical

association

between feet and the psychoanalytic process itself. In 1907, Freud

published his Delusions and Dreams in Jensen's `Gradiva', a study

of a story by William

Jensen published in 1903, which describes the obsession of Dr. Norbert

Hanold, an archaeologist, with a marble figure depicting a woman with a

characteristically lifted gait. Hanold names this figure `Gradiva', the

`girl who steps along'. Looking in vain for her style of walking among

real women in the city, he becomes convinced that he has found her as a

revenant in the city of Pompeii, of which he believes she has been an inhabitant

in AD 94, the year of the catastrophic eruption which buried the city.

Gradually it is revealed that his ghost is in fact a childhood friend,

Zoe Bertgang, whose German name (`bright walker') is almost identical to

the name Hanold has given the sculpture. She has recognised Hanold, and

resolved to play the part of Gradiva in order to cure him both of his forgetfulness

of her and of his lifelong repression of erotic feelings.

Freud associates Hanold's `pedestrian researches' with his own psychoanalytic

enquiry; but much more important for Freud than the association between

Hanold

and himself is the far-reaching similarity -- no, 'a complete agreement

in its essence' between Zoe Bertgang's method of lifting repression and

the `therapeutic method

which was introduced into medical practice in 1895 by Dr. Josef Breuer

and myself' (SE, IX, 88-9). Indeed, Zoe Bertgang can go further even than

psychoanalysis,

since `Gradiva was able to return the love which was making its way

from the unconscious into consciousness, but the doctor cannot' (SE, IX,

90). Zoe, as her

name suggests, is life-giving. While her therapy is archaeological

in broadly the same way as psychoanalytic therapy, it is also associated

with the zoology (the

scientific occupation of her father), which sets her work against the

more morbid kinds of disinterral involved in the psychoanalytic `work of

spades (Arbeit des

Spatens)' (SE, IX, 40; GS, 9, 307). Zoe steps athletically into the

shoes of Gradiva, identifying herself with Hanold's unconscious delusions

in order to free him from

them. Psychoanalysis is condemned to the melancholy pursuit of traces,

like the Hanold who comes to Pompeii to look for the distinctive imprint

of Gradiva's passing

in footprints left in the ash (SE, IX, 17).

It appears that there are in fact two kinds of walking, or `pedestrian

researches' in Gradiva. This is literally the case, for, as Rachel

Bowlby points out, the phrase `pedestrian researches', which Strachey uses

twice, translates two slightly different phrases in Freud's German, pedestrischen

Prüfungen

and pedestrischen

Untersuchungen (Bowlby 1992, 181-2; GS 9, 326); Prüfung

sometimes has more the sense of a specific test or examination than Untersuchung,

which can refer

to a more generalised investigation.), and that they are concentrated

together in the description of the bas-relief of Gradiva (Freud himself

owned a cast of this

bas-relief, like Hanold):

The sculpture represented a fully-grown girl stepping along, with her flowing dress a little pulled up so as to reveal her sandalled feet. One foot rested squarely on the ground; the other, lifted from the ground in the act of following after, touched it only with the tips of the toes, while the sole and heel rose almost perpendicularly. (SE, IX, 10)

Gradiva is here caught as it were photographically between standing

and walking. She both acknowledges and spurns what is underfoot, at once

standing her

ground, and standing clear of it. Compared with the elastic spring

and poise of Gradiva's step, psychoanalysis appears to be a creeping and

ignoble procedure,

always unsure of its footing. Throughout Freud's account of the story,

Hanold's growing understanding is represented in terms of feet, walking

and steady progress:

`It could not be disputed that this clear insight into his delusion

was an essential step forward on his road back to a sound understanding

(einen wesentlichen

Fortschritt auf dem Rückung zur gesunden Vernunft)' (SE, IX, 28;

GS, 9, 296); `The young man, who had earlier been obliged to play the pitiable

part of a

person in urgent need of treatment, advanced still further (weiter

schreitet) on the road to recovery' (SE, IX, 38; GS, 9, 305); `The

journey, which was undertaken

in defiance of the latent dream-thoughts, was nevertheless following

the path (folgt doch der Weisung) to Pompeii' (SE, IX, 67; GS, 336-7).

Even Hanold's

delusions appear more direct and purposive than the cautious, repetitious

movement of psychoanalysis: `Norbert Hanold's delusion...was carried a

step further

(erfahre eine weitere Entwicklung)' (SE, IX, 54; GS, 9, 323).

Associated not with life, but with death, not with zoology, but with the

`roundabout path by way of

archaeology' disdained by Zoe (SE, IX, 37), psychoanalysis must accordingly

accept slow progress, and frequent loss of bearings. `No, we must try another

path

(einem anderen Wege)' (SE, IX, 56; GS, 9, 325); `Here again there seems

no path to an understanding (kein Weg zur Aufklärung)' (SE,

IX, 57; GS, 9, 326).

Not the least of the disadvantages of psychoanalytic reading is the

fact that it must go over the ground twice, where Zoe is able to effect

her cure miraculously, `by

taking up the same ground as the delusional structure (auf dem Boden

des Wahngebäudes stellen) SE, IX, 22; GS, 9, 288), from within Hanold's

delusions. Late

in his essay, Freud devotes some admiring pages to the ambiguous language

which is given to Zoe by the author of the story, a language which enables

her `to

express the delusion and the truth in the same turn of words' (SE,

IX, 84). Freud, on the other hand,is condemned to a much more laborious

procedure, in which the

telling of the story must be separated from the analysis of it:

Now that we have finished telling the story

and satisfied our own suspense, we can get a better view of it, and we

shall now reproduce it with the

technical terminology of our science, and

in doing so we shall not feel disconcerted at the necessity for repeating

what we have said before. (SE, IX,

44)

The limited nature of the cure effected by psychoanalysis is suggested,

as we have seen, by the fact that the doctor cannot return or complete

the love that he brings

to consciousness in his patient. Freud expresses the distinction between

Bertgang's intimate `cure by love' and the distance of his own in a rather

distinctive way.

`The doctor', he writes, `has been a stranger (ein Fremder), and must

endeavour to become a stranger once more after the cure' (SE, IX, 90; GS,

9 361). These

words betray the larger sense in which Freud appears to see psychoanalysis

as an alien intrusion. The rivalry between clinical and romantic psychoanalytic

cure, each

with its distinctive Gang, gait, or way of proceeding, is also an ethnic

rivalry. On two occasions, Freud characterises the relationship between

Hanold and

Gradiva/Bertgang in terms that emphasise their racial homogeneity.

When Hanold speaks to Zoe first in Greek and then in Latin, she replies

` "If you want to speak

to me...you must do it in German' ' (SE, IX, 18). Freud's interpolated

response, `What a humiliation for us readers!' (SE, IX, 18), assumes that

we have been

identifying with Hanold's delusion and share his discomfiture. But

there may be another humiliation lurking behind this one, in Freud's sense

of not being included in

the closed circle of reciprocity established between author, addressor,

addressee and reader. The succession of wes that follow in Freud's text

seems to underline

this sense of anxiety at the capacity of the German girl to effect

her own version of the `talking cure' with her German patient, one which

relies upon enactment rather

than dissective analysis, and on shared ethnic intuition and experience

rather than painstaking explication. Compared with this, what was already

being thought of as

the Jewish science of psychoanalysis appears vulgarly intrusive.

More strikingly, there is the passage in which Freud allows the play

of his own phantasy to produce a possible justification for the implausibility

on which Gradiva is

based, namely the coincidence of the exact correspondence between the

gait of Gradiva depicted in Hanold's bas-relief and the gait of the living

Zoe.

The name of `Bertgang' might point to the fact

that the women of that family had already been distinguished in ancient

days by the peculiarity of their

graceful gait; and we might suppose that the

Germanic Bertgangs were descended from a Roman family one member of which

was the woman who

had led the artist to perpetuate the peculiarity

of her gait in the sculpture. Since, however, the different variations

of the human form are not independent

of one another, and since in fact even among

ourselves the ancient types re-appear again and again (as we can see in

art collections), it would not be

totally impossible that a modern Bertgang

might reproduce the shape of her ancient ancestress in all the other features

of her bodily structure as well.

(SE, IX, 42)

In rescuing the psychoanalytic tale of Jensen from implausibility, and

making it consistent with itself, Freud allows a vision of closed, renewing

racial homogeneity

which appears worryingly superior to the psychoanalytic intervention

of the `stranger'. Sander Gilman suggests that we need to read Jensen's

tale, which he describes

unequivocally as the tale of `a Germanic foot in all its glory'

(1993, 146), independently of and against the grain of Freud's identification

with it, to reveal it as `the

family romance of a race, the northern Germans, who find themselves

in the classical world, which is itself German' (1993, 147). But this passage

suggests that

Freud may also be intimating a complex challenge to the model of closed

ethnic recurrence suggested in Jensen's Gradiva. For, after allowing the

play of his own

phantasy of hereditary persistence, Freud then, somewhat abruptly,

withdraws it:

But it would no doubt be wiser, instead of

such speculations, to enquire from the author himself what were the sources

from which this part of his

creation was derived; we should then have

a good prospect of showing once again how what was ostensibly an arbitrary

decision

rested in fact upon

law. But since access to the sources in the

author's mind is not open to us we will leave him with an undiminished

right to construct a development that

is wholly true to life upon an improbable

premiss. (SE, IX, 42-3)

With this, Freud opens the possibility that the whole of the allegedly

self-grounding analytic technique for reading delusions may itself be founded

upon an

extravagant delusion, and that, far from being hermeneutically self-sufficient

or spontaneously self-knowing, it would rely upon outside help, the help

of an outsider,

for the repair and maintenance of its truth.

The metaphor of feet and the associated figural repertoire of terms

suggesting grounding and progress continue to be important in Freud's work.

What is more, it

operates in attacks upon it, such as those mounted in later years by

Jung, who features in Freud's essay as the unnamed intermediary between

the German and the

Jewish worlds, since it was he who brought Freud's attention to Jensen's

Gradiva. In his essay `The Role of the Unconscious' of 1918, Jung argues

that the

categories of `Jewish' psychoanalysis are inadequate for the understanding

of the German or Aryan psyche. This is because of a fundamental difference

between the

two races in terms of their relation to the earth. The German is characterised

by the intensity of his sense of rootedness in the earth. Although the

Jew has a history of

cultural achievement to sustain him, he is, by contrast, `badly at

a loss for that quality in man which roots him to the earth and draws new

strength from below' (Jung

1970, 13). It is the anachthonic nature of the Jew ?`where has he his

own earth underfoot?' Jung demands (1970, 13) ?which produces in him a

compensating

desire to reduce psychical experiences to their material beginnings,

and yet also protects him against the dangerous effects of exposure to

unconscious forces.

Psychoanalysis supplies the homeless Jew with a fantasised over-investment

in materiality which the Aryan neither needs nor could tolerate. Thus,

though Jung does

not subscribe to Freud's theory of fetishism, he here explains Freudian

explanations according to terms which seem to borrow from that theory.

Deprived of any

authentic relation to the ground, the Jew produces its fetishistic

substitute; the substitute however only continues to testify to the fact

of dispossession, and the lack of

grounded being. The double-bind in which the Jew is accused both of

reducing everything to the body, and of having an inadequate relationship

to it, reproduces the

structure of double accusation to which I drew attention earlier in

this essay.

The most normal step has to bear disequilibrium,

within itself, in order to carry itself forward, in order to have itself

followed by another one, the same

again, that is a step, and so that the other

comes back, amounts to the same, but as other. Before all else limping

has to be the very rhythm of the

march, unterwegs. Before any accidental

aggravation which could make limping itself falter. This is rhythm.

(Derrida 1987a, 406).

(I have commented myself on the significance of this final quotation

in Beyond the Pleasure Principle: Connor 1992, 70-1.) Sander Gilman sees

anxiety and

apologetic self-abasement in Freud's acknowledgement of the limping

nature of so-called Jewish science (1993, 137-8); but I think it is also

possible to see this as a

more confident introjection of negativity, which leads Freud positively

to promote the acceptance of the limping nature of all cultural endeavour,

maimed as it is by its

compromises with the death drive. In this, Freud seems to be in touch

with a current within avant-garde and modernist culture which had begun

to embrace and even

as it were promote the degenerate body of the fin-de-siècle

imagination. In the work of the surrealists, and perhaps especially

Magritte, Bunuel and Bataille, there is a strikingly insistent attention

paid to the foot. In his essay on `The Big Toe', which appeared in

the renegade surrealist journal Documents in 1929, accompanied by some

remarkable photographs of toes by Jacques-André Boiffard, Bataille

insisted that the foot was simultaneously `the most human part of the human

body, in the sense that no other element of this body is as differentiated

from the corresponding element of the anthropoid ape' and yet that part

of the body which is closest to the base element of mud, which human culture

wishes to disavow in itself: `whatever the role played in the erection

by his foot, man, who has a light head, in other words a head raised to

the heavens and heavenly things, sees it as spit [crachet], on the pretext

that he has this foot in the mud' (1985, 20). Bataille's comments help

me to make the transition between Freud's responses to the alleged degeneracy

of the Jewish foot, to the fortunes of the Irish foot, as they are insisted

on in the work of Joyce and Beckett, both writers in whose work, the question

of Jewishness also bulks large.

In the work of Joyce in particular, feet, and various forms of footwear,

are conspicuous bearers of cultural belonging and difference. Just as Freud

begins by

attempting to distance himself from the degenerate Jewish foot and

its associations, Joyce defines his own deracinated, cosmopolitan avant-gardism

against the

counter-image of the Irish boot. More than any other item of

footwear, the boot testifies to the slovenly indistinction of the subject

and the subjacent ground it

occupies. One early counter-image to the boot is found in the goloshes

worn by Gabriel and Gretta Conroy to the Morkans' Christmas party in `The

Dead' in

Dubliners. The goloshes stand for Gabriel's cultural aloofness, and

refusal of assimilation to the nationalist cause and sensibility (Joyce

1993, 341). Gabriel's

fastidiousness with regard to the relation between his feet and the

ground seems to have been shared by his author, who is known himself to

have taken pride in the

daintiness of his own feet and smart footwear. Richard Ellmann reproduces

in his biography of Joyce a story told by Wyndham Lewis which, whether

or not it is true

in every detail, seems to provide a strikingly particularised commentary

on the cultural-political meanings of feet, footwear and bodily posture

in the Joyce circle. The

story concerns a meeting in Paris in 1920 between Lewis, T.S. Eliot

and Joyce. Eliot has been entrusted with a parcel for Joyce by Ezra Pound.

Joyce lay back in the stiff chair he had taken from behind him, crossed his leg, the lifted leg laid out horizontally upon the one in support like an artificial limb, an arm flung back over the summit of his sumptuous chair. He dangled negligently his straw hat, a regulation `boater'. We were on either side the table, the visitors and ourselves, upon which stood the enigmatical parcel...

James Joyce was by now attempting to untie

the crafty housewifely knots of the cunning old Ezra...At last the strings

were cut. A little gingerly Joyce

unrolled the slovenly swaddlings of damp British

brown paper in which the good-hearted American had packed up what he had

put inside.

Thereupon...a fairly presentable pair of old brown shoes stood revealed, in the centre of the bourgeois French table...

James Joyce, exclaiming very faintly `Oh!'

looked up, and we all gazed at the old shoes for a moment. `Oh!' I echoed

and laughed, and Joyce left the

shoes where they were, disclosed as the matrix

of the disturbed leaves of the parcel. He turned away and sat down again,

placing his left ankle upon his

right knee, and squeezing, and then releasing,

the horizontal limb. (quoted, Ellmann 1982, 493)

This narrative neatly condenses the repertoire of attitudes and postures

relating to the foot with its miniature drama of offered and refused national

origin. Lewis

suspends Joyce awkwardly in mid-air, embarrassed by the grotesque vulgarity

of the gift sent to him by Pound -- himself, of course, like all the other

figures present

at the scene, a cultural exile -- , which seems to embody all the feminine,

maternal, vegetable claims of Ireland over Joyce. A curious verification

of the

chthonophobia, or distaste for the ground, revealed in this story is

the peculiar, high-kicking dance ?he calls it a pas de seul ?which Joyce

liked to perform on

his birthday. The dance is alluded to in a letter to Viscount Carlo

of 28 January 1939, a couple of days before what would prove to be Joyce's

last birthday (Joyce

1975, 395).

The claims of nation appear in a similar way in the `Proteus' chapter

of Ulysses, which shows Stephen Dedalus walking on Sandymount Strand and

reflecting on the

protean nature of perception, materiality and art. In `Proteus', what

is underfoot is the formless, clinging, female world of matter, which is

to be transformed by the

artist into meaning: `Signatures of all things I am here to read, seaspawn

and seawrack, the nearing tide, that rusty boot' (U, 31; 3:2-3). The boot

is associated both

with the insidious mutability of the sea and shifting sand, and with

the philosophical and psychological bulwarks Stephen erects against mutability:

The grainy sand had gone from under his feet. His boots trod again a damp crackling mast, razorshells, squeaking pebbles, that on the unnumbered pebbles beats, wood sieved by the shipworm, lost Armada. Unwholesome sandflats waited to suck his treading soles, breathing upward sewage breath, a pocket of seaweed smouldered in seafire under a midden of men's ashes. He coasted them, walking warily. (U, 34; 3:147-52)

Stephen feels the danger of engulfment throughout the chapter: `He stood

suddenly, his feet beginning to sink slowly in the quaking soil...Turning,

he scanned the

shore south, his feet sinking again slowly in new sockets...He lifted

his feet up from the suck and turned back' (U, 37; 3:268, 270-1, 278-9).

The engulfing agency is

at once nation, mother, earth and history (`These heavy sands are language

tide and wind have silted here', thinks Stephen, U, 37; 3:288-9).

Waves and water signify a mingling of identity that fills Stephen with

horror. `Their blood is in me, their lust my waves' he thinks as he recalls

the Danish founders of

the city of Dublin (U, 38; 3:306-7). Water suggests not only personal

extinction, but the interchange of identity: Stephen panics at the thought

of being called upon to

imitate his friend Buck Mulligan's feat of saving a drowning man, since

this seems to involve the necessity of a physical mingling: `Do you see

the tide flowing quickly

in on all sides, sheeting the lows of sand quickly, shellcocoacoloured?

If I had land under my feet. I want his life still to be his, mine to be

mine (U, 38; 3:326-8). But

the watery instability of identity which is felt throughout this chapter

begins to draw Stephen irresistibly into identification with other lives,

other bloods. Among these

are the cocklepickers whom Stephen sees wading into the sea and walking

along the sand. Their seductive strangeness is concentrated for Stephen

in their bare feet:

Shouldering their bags they trudged, the red

Egyptians. His blued feet out of turnedup trousers slapped the clammy sand,

a dull brick muffler strangling

his unshaven neck. With woman steps she followed:

the ruffian and his strolling mort. Spoils slung at her back. Loose sand

and shellgrit crusted her

bare feet. (U, 39; 3:370-4)

These generalised "Egyptians', or gypsies, are members of a wandering

race, whose diasporic multiplication of language and historical identities

Stephen mimics in his

interior monologue: `Across all the sands of the world...She trudges,

schlepps, trains, drags, trascines her load....Tides, myriadislanded, within

her, blood not mine'

(U, 40; 3:391-4). Significantly, Stephen's reflections on their wandering

seem to spring directly out of his memory of a premonitory dream he had

the night before, a

dream in which he is being invited into an Oriental house, perhaps

a brothel, by a figure he comes to identify as the Jewish Bloom.

Perhaps one of the reasons for the importance of shoes in the imagination

of identity in modernism consists in the fact that shoes are at once

among the most

intimately one's own of any item of clothing, and yet are also separable

from the body, and available for swapping, borrowing and substitution.

`If I were in your shoes', we say, not `If I were in your shirt', or `If

I were under your hat'. It is presumably this ambivalence which allows

for the fetishistic investment in shoes. This sense of intimate estrangement

or estranged intimacy affects Stephen particularly in the `Proteus' chapter

because the boots upon which he is relying to protect him from engulfment

are not even his own, but borrowed from the mocking, threatening Buck Mulligan.

As the chapter proceeds, the phallic petrifaction of identity

concentrated in Stephen's footwear begins to loosen:

His gaze brooded on his broadtoed boots, a

buck's castoffs, nebeneinander. He counted the creases of rucked leather

wherein another's foot had

nested warm. The foot that beat the ground

in tripudium, foot I dislove. But you were delighted when Esther Osvalt's

shoe went on you. Girl I knew in

Paris. Tiens, quel petit pied! (U, 41; 3:446-50)

The boot that had earlier asserted its stiff self-sufficiency against

a decomposing and transforming protean exterior is drawn into a series

of substitutions and

transformations, as Stephen playfully identifies himself with the previous

occupant of the boots, and remembers with pleasure being able to wear the

shoe of an

acquaintance in Paris (as far as I know, this character has not been

identified, though her name suggests the possibility that she is Jewish).

At the end of the chapter,

Stephen is mentally preparing his own journey, with `My cockle hat

and hismy sandal shoon', trekking, like the `Egyptians' `to evening lands'

(U, 42; 3:487-8).

Leopold Bloom's most extended encounter with the metamorphic powers

of the foot takes place in the `Circe' chapter of the novel, which finds

Stephen and Bloom

in a brothel in Dublin's Tyrone Street. The extravagant sensual degradation

of this chapter, which mimics the transformation of Odysseus's crew into

swine in the

Odyssey, is prepared for in its opening pages through the motif of

animal feet. Bloom, concerned that Stephen should have some food inside

him to offset the effects

of the alcohol he has consumed, goes into the pork butcher Olhausen's

to purchase a sheep's trotter and a crubeen, or pig's trotter. He is confronted

by a vision of

his suicide father `garbed in the long caftan of an elder in Zion',

and hides the crubeen and trotter guiltily behind his back as he recalls

an earlier occasion of drunken

humiliation, when challenged to a sprint by some members of a running

club ?`It was muddy. I slipped' (U, 358; 15:277). This apparition gives

way to that of

Molly Bloom, dressed in Turkish garb, Bloom's attention being drawn

to her `jewelled toerings' and ankles `linked by a slender fetterchain'

(U, 359; 15:312-13).

Molly's mockery ?`Has poor little hubby cold feet waiting for so long?'

(U, 359; 15:307) ?now seems to transfer Bloom's uneasiness about the crubeen

and

sheep's trotter to his own feet, as he indeed, as the stage direction

tells us, `shifts from foot to foot' (U, 359; 15:308). This brings about

the first of a number of

symbolic and actual prostrations for Bloom, the `poor old stick in

the mud', as Molly calls him, reminding him of the fiasco of the drunken

sprint (U, 359;

15:329-30); Molly's attendant camel, `lifting a foreleg, plucks from

a tree a large mango fruit, offers it to his mistress, blinking, in his

cloven hoof, then droops his

head and, grunting, with uplifted neck, fumbles to kneel. Bloom stoops

his back for leapfrog' (U, 359; 15:320-3).

This prelude anticipates Bloom's extended fantasy (if it is his own

exactly, which is not certain) of masochistic subordination to Bella Cohen,

the keeper of the

brothel. Bloom's swinish degradation involves him sinking to the ground

to pay homage to the porcine hoof of Bella, now transformed into the gruffly

masculine

Bello. The feminisation of Bloom accords closely with turn-of-the-century

stereotypes of the effeminate Jewish man, as Robert Byrnes has argued (1990),

as does

his anxious enjoyment of the `heel discipline in gym costume' (U, 433;

15:2869-70) threatened by Bello. Bloom pays excessive and particularised

homage to Bello's

shoe:

BLOOM: (murmurs lovingly) To be a shoefitter

in Mansfield's was my love's young dream, the darling joys of sweet buttonhooking,

to lace up

crisscrossed to kneelength the dressy kid

footwear satinlined, so incredibly impossibly small, of Clyde Road ladies.

Even their wax model Raymonde I

visited daily to admire her cobweb hose and

stick of rhubarb toe, as worn in Paris. (U, 432; 15:2813-18)

Bello mocks Bloom for his sexual inadequacy ?`What else are you good

for, an impotent thing like you?' (U, 441; 15:3127) ?taunting him as a

`lame duck' (U,

442; 15:3149) and a `flatfoot' (U, 442; 15:3176), and conjuring

up the chaos wreaked in his home by the bestial seducers who s/he says

have taken it over ?

`Their heelmarks will stamp the Brusselette carpet you bought at Wren's

auction' (U, 443; 15:3183-4). Here the alleged sexual inadequacy of Bloom

is strongly

associated with the double power of the foot. Sunk to the condition

of what lies underfoot, Bloom is neatly transformed into a quadruped, with

hands serving as feet,

by the agency of a phrase remembered from Eugen Sandow's Physical Strength

and How to Obtain It (a copy of which we know he owns):

BELLO: Down! (he taps her on the shoulder with

his fan) Incline feet forward! Slide left foot one pace back! You will

fall. You are falling. On the

hands down! (U, 433; 15: 2846-9)

But if the foot is the mark of the abased, perverted, womanly man

of anti-Semitic imagination, Bloom's fetishistic investment of the foot

also fills it with phallic authority. Like most other objects in the

`Circe' chapter, Bello's hoof actually speaks, barking out `Smell my hot

goathide. Feel my royal weight' (U, 432; 2820) and `If you bungle, Handy

Andy, I'll kick your football for you' (U, 432; 2824). In fact, the fetishising

of the foot as the penis is part of the comic puncturing of masculinity

which is celebrated throughout the sequence. For it is not only Bloom's

shapeshifting, foot-centred womanliness that is a masquerade, but masculinity

itself.

The movement away from the modernist dream of disembodied, postterritorial

flight in Joyce's work takes the form of the acceptance of the foot's alterity.

Bloom's

ambivalent return, in the penultimate `Ithaca' chapter of the novel,

to his uncertain home is marked, among many other ceremonies of atonement

and reconciliation,

by the removal of his boots in the chapter. The ceremony of divestiture

enacts the balanced relationship that Bloom seems to have achieved to his

own body; looking

with generous curiosity at `the creases, protuberances and salient

points caused by foot pressure in the course of walking repeatedly in several

different directions',

the contemporary Ulysses recalls the action of Penelope in her nocturnal

unweaving of her tapestry as he `disnoded the laceknots, unhooked and unloosened

the

laces, took off each of his two boots for the second time' (U, 584;

17:1483-4), seeming in the process to unloose himself from the tightlaced

corsetry of fetishistic

thought to which he has been subject in the `Circe' chapter in the

brothel. His olfactory autostimulation as he `picked at and gently lacerated

the protruding part of

the great toenail, raised the part lacerated to his nostrils and inhaled

the odour of the quick, then, with satisfaction, threw away the lacerated

ungual fragment' (U,

585; 1488-91), nicely embodies the equilibrium of egoity and alterity

attained by Bloom at the end of the day, as `a solitary (ipsorelative)

mutable (aliorelative) man'

(U, 581; 1350).

The transferential drama of the Irishman (Joyce-Dedalus) who comes home

through an identification with the Jewgreek (Bloom-Odysseus) accommodating

himself

to his domestic dispossession, is played out in the way in which Joyce

first refuses, then slowly adjusts himself in Ulysses to the ignoble grounding

of the self

embodied in the foot. Very much more would need to be said than I have

space for here about the subsequent effects of this adjustment in Finnegans

Wake

(1939), the book of the night, in which writing, working and walking

are insistently interlaced (`I am treading this winepress alone', Joyce

wrote in 1937 - Joyce

1975, 385), and in which the restless somnambulism of feet, boots and

shoes paces out the peregrinations of national and cultural identity. Against

all the rooted

readerly prejudices of what Joyce called the `terrafirmaite' (Joyce

1950, 190), there is the Joyce-like figure of Shem, the `Irish emigrant

the wrong way

out...semisemitic serendipitist...Europasianised Afferyank' (Joyce

1950, 191) with 'not a foot to stand on` (Joyce 1950, 169). Indeed the

very beginnings of the

book are in a notebook which has become known, accidentally, but for

my purposes providentially, through its first word, as the "Scribbledehobble'

notebook

(Connolly 1961).

For Beckett it is above (or really, I suppose, below) all the function

of the foot to embody embodiedness itself, and the maladjustment of the

self and its corporeal

dimensions. Beckett's loving and versatile interest in limping, spavined,

toppling, and otherwise impaired modes of the peripatetic is apparent throughout

his work. It

is instanced for example in the marvellous description of the `headlong

tardigrade' motion of Watt in the novel that bears his name (Beckett 1963,

29). But it is

nowhere better epitomised than in the meticulously chaotic analysis

in Molloy (1950) of the confusingly transposed afflictions in Molloy's

two legs. If Molloy, like all

of Beckett's everyman-nomads, is a kind of Wandering Jew, an association

which has been analysed by Rosette C. Lamont (1990), then this passage

lifts the

archetypal weakness of the Jewish foot and leg, as embodied perhaps

in the condition of intermittent claudication analysed by Gilman, into

a complete philosophical

principle or way of (non)proceeding.

And now my progress, slow and painful at

all times, was more so than ever, because of my short stiff leg, the same

which I thought had long been as

stiff as a leg could be, but damn the bit

of it, for it was growing stiffer than ever, a thing I would not have thought

possible, and at the same time shorter every day, but above all because

of the other leg, supple hitherto and now growing rapidly stiff in its

turn, but not yet shortening, unhappily. For when the two legs shorten

at the same time, and at the same speed, then all is not lost, no. But

when one shortens, and the other not, then you begin to be worried...Let

us try to get this dilemma clear. Follow me carefully. The stiff leg hurt

me, admittedly, I mean the old stiff leg, and it was the other which I

normally used as a pivot, or prop. But now this latter, as a result of

its stiffening, I suppose, and the ensuing commotion among nerves and sinews,

was beginning to hurt me even more than the other. What a story, God send

I don't make a balls of it. For the old pain, do you follow me, I had got

used to it, in a way, yes, in a kind of way. Whereas to the new pain, though

of the same family exactly, I had not yet had time to adjust myself. (Beckett

1959, 77)

With its agonised hopping from foot to foot, and its scarcely-regulated

rhythm of tottering antithesis, Molloy's reasoning is indeed a scribbledehobble,

in which

writing and thinking are an iambic limp, or Freudian démarche,

alternating progress and stasis: `Yes, my progress reduced me to stopping

more and more often, it

was the only way to progress, to stop....I hobble, listen, fall, rise,

listen and hobble on' (Bekcett 1959, 78). The ill-assorted feet and legs

are a type of the

argumentative twinnings or `pseudocouples' of all kinds that throng

Beckett's work, whether in the form of characters (Mercier and Camier,

Vladimir and Estragon,

Hamm and Clov), or more abstract dualities (mind and body, French and

English, speaker and hearer, torturer and victim). Molloy's legs, and his

manner of writing

them, mark the disinclination to immunise art from the principles of

abjection and decomposition that the feet, and especially the Irish and

the Jewish feet, represent

for modernism.

Whereas in the middle period of Beckett's writing, the period of the

Trilogy of novels and the first plays, the feet signify the recalcitrance

of the moribund body, in

later work, the feet are characterised by a spectral insubstantiality,

and concentrate the sense of a perplexed relationship between the subject

and the grounds of its

cultural and historical belonging. This begins in fact with the famous

boots of Estragon in Waiting for Godot (and in what follows, it may not

be irrelevant to

remember that Estragon was given the name `Levy' in the early drafts

of the play). In one sense, it could be said that Estragon's boots are

the simple symbolic

opposite to Vladimir's hat, since Estragon represents the unconscious

appetites and impulses of the body as opposed to Vladimir's anguished rationality.

But the boots also dramatise the failure of continuity between the self

and the spatial and temporal contexts that give it meaning. In Act 1

of Waiting for Godot, Estragon discards his boots because they are too

tight. At the beginning of Act 2, Vladimir points triumphantly to the

boots as proof that the two are in the very spot where they waited in vain

for Godot the previous night:

ESTRAGON: They're not mine.

VLADIMIR: [Stupefied.] Not yours!

ESTRAGON: Mine were black. These are brown.

VLADIMIR: You're sure yours were black?

ESTRAGON: Well, they were a kind of grey.

VLADIMIR: And these are brown? Show.

ESTRAGON: [Picking up a boot.] Well, they're

a kind of green.(Beckett 1986, 60-1)

The audience's certainty that they are indeed in the same place is undermined

by Vladimir's acknowledgement that the boots are indeed different. The

interchange

that follows has something of the asymmetrical gait of Molloy's narrative:

VLADIMIR: It's elementary. Someone came and

took yours and left you his.

ESTRAGON: Why?

VLADIMIR: His were too tight for him, so he

took yours.

ESTRAGON: But mine were too tight.

VLADIMIR: For you. Not for him. (Beckett 1986,

61)

There have been a number of suggestions that Beckett's Trilogy and Waiting

for Godot may derive from Beckett's experience after his flight from Paris

after its

occupation and his undercover existence in the town of Roussillon in

the Vichy quarter of France, still occasionally undertaking missions for

the Resistance. The

sense of uncertainty and danger attaching to Beckett's own national

identity may have helped enforce the sense of the parallel between his

situation and that of his

many Jewish friends, a number of whom, such as Paul Léon, and

Alfred Péron, suffered deportation and were murdered in concentration

camps. (I have heard of a

story related by a friend of Beckett that Beckett wore the Star of

David during his time in Paris as a mark of solidarity with Jewish friends

required by the Germans

to wear the symbol.) Leslie Hill has pointed to the importance of some

of the names in Beckett's writing of the forties -- of the mysterious character

Youdi in Molloy,

for example, whose name is both an inversion of `Dieu' and close to

a French slang term for `Jew', or the homicidal Lemuel, whose name identifies

him not only with

Swift's Gulliver, but also with Beckett's own Christian name, the Jewish

provenance of which is signalled on Lemuel's first appearance in Malone

Dies: `My name is

Lemuel, he said, though my parents were probably Aryan' (Beckett 1959,

267). Leslie Hill (1990, 98-9, 107-11) has discussed other Judaic qualities

of Beckett's

writing. And a peculiar addition to Beckett's association with Jewishness

may be provided by the fact that Joyce's daughter Lucia, with whom Beckett

had a

disastrously unsuccessful affair when she was already suffering from

the mental disturbance that was to develop into schizophrenia, came to

believe that Beckett was

`half Jewish' (quoted, Hayman 1983, 76).

We may speculate with some confidence (or I can, anyway) that for Beckett, as for many other displaced or exiled modernist artists, Jewishness comes to epitomise displacement itself, the absence of the ground underfoot, in Jung's phrase that I quoted earlier. Nowhere is this spectral as opposed to abject foot shown more starkly than in Beckett's late play Footfalls (1976), which centres on a woman who paces up and down a narrow strip of light, while the audience hears her voice and that of an older woman, perhaps her mother, telling the story, perhaps her own, of a young girl for whom the intense but thwarted desire to `be there' is expressed in walking, and the relation of the foot to the ground. As we watch `M' walk up and down, the voice of 'V' addresses us:

V: I say the floor here, now bare, this strip

of floor, once was carpeted, a deep pile. Till one night, while still little

more than a child, she called her

mother and said, Mother, this is not enough.

The mother: Not enough? May ?the child's given name ?May: Not enough. The

mother: What do you

mean, May, not enough, what can you possibly

mean, May, not enough? May: I mean, Mother, that I must hear the feet,

however faint they fall. The

mother: The motion alone is not enough? May:

No, Mother, the motion alone is not enough, I must hear the feet, however

faint they fall. (Beckett 1986,

401)

Beckett's spectral poetics of the foot anticipate the remarkable

preoccupation with the foot in postmodern theory, most notably in Derrida's

pained exploration

(1987b) of the themes of ownership, unbelonging and attribution played

out through Meyer Schapiro's remarks regarding Heidegger's essay on Van

Gogh's paintings

of peasant shoes. This exploration is taken further in Fredric Jameson's

nuanced lament for the loss of authentic modernist grounding as embodied

in Van Gogh's

painting, at least as it is interpreted by Heidegger, and the ungrounded

affectless pastiche of Andy Warhol's Diamond Dust Shoes (Jameson

1992, 6-11)

For Derrida, the foot and the shoe that covers it is the sign of a failure of fit, or series of such failures: between the foot and the underfoot; the foot and its owner; the shoe and its pair; the shoe and its wearer; the image of the shoe and the shoe `itself': `a work like the shoe-picture exhibits what something lacks in order to be a work, it exhibits ?in shoes ?its lack of itself' (Derrida 1987b, 298). Derrida's stravaging, footloose meditation on Van Gogh, Heidegger, Freud and others throws up at one point a melancholy literalisation of the theme of dispossession, in an evocation of the shoes abandoned outside the gas chambers:

But an army of ghosts are demanding their shoes.

Ghosts up in arms, an immense tide of deportees searching for their names...the

bottomless memory

of a dispossession, an expropriation, a despoilment.

And there are tons of shoes piled up there, pairs mixed up and lost. (Derrida

1987b, 329-31)

Perhaps, however, these ghosts can never be satisfied, since it seems

to have become the function of the foot and the shoe in our century

to instance spectrality, dispossession, and failure to `be there' themselves.

It has not been my intention to imply the simple equivalence of the different

experiences of exile, dispossession, and the loss of the ground of belonging

enacted through the Jewish and the Irish writing of the foot. Rather it

has been to see in the transmitted preoccupation with the foot between

Jewish and Irish writing the shape of a transferential `ghosting' of identity,

which has no shared and palpable ground on which to take its stand, but

still, in its faltering pas de deux, moving in and out of step, marks out

in miraculous mid-air a kind of `under-standing'.

Bataille, Georges (1985). `The Big Toe.' In Visions of Excess: Selected

Writings, 1927-1939, trans. Allan Stoekl, Carl R. Lovitt and Donald M.

Leslie, Jnr

(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985).

Beckett, Samuel (1959). Molloy. Malone Dies. The Unnamable. London:

Calder and Boyars.

-------------------- (1963). Watt. London: Calder and Boyars.

-------------------- (1986). Complete Dramatic Works. London: Faber

and Faber.

Bowlby, Rachel (1992). `One Foot in the Grave: Freud on Jensen's Gradiva.'.

In Still Crazy After All These Years: Women, Writing and Psychoanalysis

(London: Routledge).

Byrnes, Robert (1990). `Bloom's Sexual Tropes: Stigmata of the "Degenerate" Jew.' James Joyce Quarterly, 27, 303-23.

Connolly, Thomas E., ed (1961). James Joyce's 'Scribbledehobble': The Ur-Workbook For `Finnegans Wake'. Chicago: Northwestern University Press.

Connor, Steven (1992). Theory and Cultural Value. Oxford: Blackwell.

Derrida, Jacques (1987a). `To Speculate - on "Freud". ' In The Post

Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond, trans. Alan Bass (Chicago and

London:

University of Chicago Press, 1987).

-------------------- (1987b). `Restitutions of the Truth in Pointing.'

In The Truth in Painting, trans. Geoff Bennington and Ian MacLeod (Chicago:

University of

Chicago Press), pp. 255-382.

Ellmann, Richard (1982). James Joyce. 2nd edn. London: Faber and Faber.

Freud, Sigmund (1925). Der Wahn und die Träume in Jensens «Gradiva».

Gesammelte Schriften, Vol. 9 (Leipzig, Wien, Zürich: Internationaler

Psychoanalytischer Verlag).

-------------------- (1953-73). The Standard Edition of the Complete

Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Trans. James Strachey. London: Hogarth

Press.

Gilman, Sander (1991). The Jew's Body. London: Routledge.

------------------- (1993). The Case of Sigmund Freud: Medicine and

Identity at the Fin de Siècle. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Press.