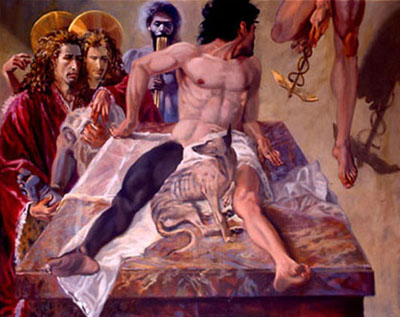

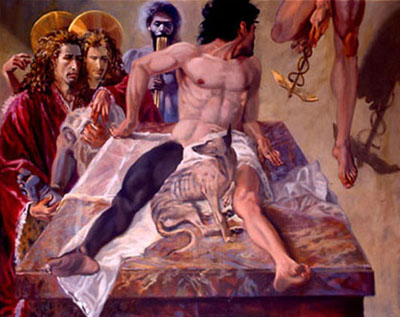

Durand (1997) The Miracle of Cosmas and Damian, oil 122cm x 152.5cm

Christ

Child with a Walking Frame (Oil on panel. Künsthistorisches Museum,

Vienna, Austria.)

Christ

Child with a Walking Frame (Oil on panel. Künsthistorisches Museum,

Vienna, Austria.)

The Wayfarer (Oil on panel Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam Diameter

70 cm)

The Wayfarer (Oil on panel Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam Diameter

70 cm)

The Beggars, Wood;

Louvre

The Beggars, Wood;

Louvre

The miracle is the painless amputation of the ulcerated leg of a Christian Roman deacon, Justinian, and the substition of the undiseased leg of a dead Ethiopian Moor.

The Burgos cathedral panels are divided between two painters, one being Alonso de Sedano, who may have painted seven of the eleven paintings, and the other called the Master of Los Balbases, to whom are attributed both the remaining four Burgos Cathedral panels and a painting of Saint Roch suffering from the plague, in the church of St Stephen in the nearby town of Los Balbases, from which his sobriquet derives.

Zimmermann KW. One leg in the grave. Maarssen Holland:

Elsevier/Bunge; 1998.

E Rinaldi, 'The first homoplastic limb transplant according

to the legend of saint Cosmas and saint Damian'

Italian Journal of Orthopedics and Traumatology, 1987,

13(3): 393-406

Douglas B Price, 'Miraculous restoration of lost body

parts: relationship to the phantom limb phenomenon and to limb-burial superstition

and practices', in W D Hand (ed) American folk medicine, Berkeley,

California, 1976, pp. 49-71.

Jacopo da Varagine Leggenda Aura (348 AD)

Durand (1997) The Miracle of Cosmas and Damian, oil 122cm x 152.5cm

St James on his way to Execution, drawing 16 x 25 cm (British Museum)

St James on his way to Execution, drawing 16 x 25 cm (British Museum)

This is the earliest surviving drawing by Mantegna. As a young artist

Mantegna painted scenes from the lives of St James and St Christopher in

the Ovetari Chapel, Church of the Eremitani, Padua (destroyed during the

Second World War (1939-45)). This preparatory drawing, in pen and brown

ink on pink prepared paper, shows St James on his way to his execution.

To the left the saint blesses a kneeling man, perhaps the figure of Josiah.

According to legend, Josiah was a scribe converted by St James when he

witnessed the saint healing a paralysed man. That man may be the figure

with his hands on his thighs, looking at St James and immediately

to his right. In the centre, a Roman soldier witnesses these events and

separates the main protagonists in the drama from the crowd of figures

to the right.

Mantegna has emphasized the figures of the saint and Roman soldier with further lines in pen and ink. Following Renaissance practice, nearly all the figures are drawn from the nude; even St James's right arm and leg are visible beneath his drapery. While most of the hatching of the background and the figures in the crowd is random and drawn very freely, the shading of the saint, scribe and soldier follows the movement of their bodies in a more naturalistic fashion.

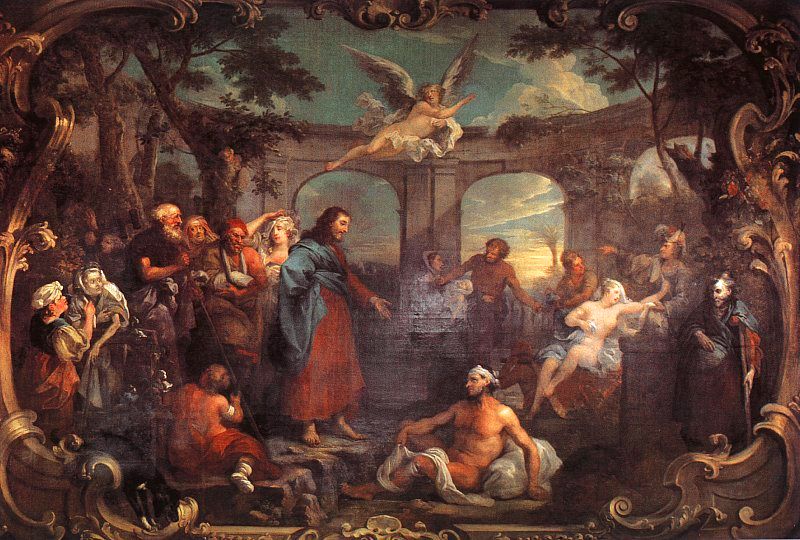

The Bible (John 5:2 - 5:14) says this scene occurs at the sheepgate, a trading area. The man at the centre is unable to walk, but we are not told why. He is shown unwinding a bandage from his leg and has another in situ on his head. Neither appears stained by blood or exudate, though to be fair on his leg there is a green patch like a pan scourer over the anterior tibia that might cover some lesion.

The charitable have diagnosed a congenital muscular dystrophy in which the muscles are enlarged but weak. If so, why the bandage? Another more interesting theory is that Hogarth, who was good with the visual pun, was casting this man as a charlatan who lived from begging. When Christ asked him "Do you want to become sound in health?" the man replied obliquely "Sir, I do not have a man to put me in the pool when the water is disturbed: while I am coming another steps down ahead of me." An unlikely excuse, really considering the 38-year history. He was told firmly "Get up, pick up your bed and walk." Hogarth might have been implying "You've been rumbled, mate, but if you go quietly I won't make a fuss".

Hogarth gave his services free of charge to Barts

Hospital, and a mixture of incentives seem to have prompted this act of

generosity. He clearly wished to prove that an English artist could excel

at the grand historical style (the Hospital Governors had considered inviting

a Venetian to paint their newly-built staircase). He had failed to secure

royal patronage, and was perhaps seeking another source of comissions.

He probably desired the status that becoming a governor of an institution

such as Barts would bring. And, perhaps most important of all, Hogarth

had strong local connections, having been born in Bartholomew Close and

brought up in the shadow of the Hospital. Hogarth wished to participate

in the philanthropic movements of the age, and what better way than to

make a generous gesture to the Hospital he knew so well. He probably used

patients as models for the sick in the picture.

Cinderella, 1863, Watercolour, 67 x 31.5 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,

Massachusetts, USA)

Cinderella, 1863, Watercolour, 67 x 31.5 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,

Massachusetts, USA)

It is the day after the ball, and in her worn and patched green gown,

the little glass slipper on her foot, she leans there dreamingly playing

with the corner of her apron; a pink rose is in a glass on the shelf, and,

on the ground beside her, half lost in the shadow, are the pumpkin and

the rat which have known such strange transformations.

Dancer Seen from

Behind and Three Studies of Feet, c. 1878

Dancer Seen from

Behind and Three Studies of Feet, c. 1878

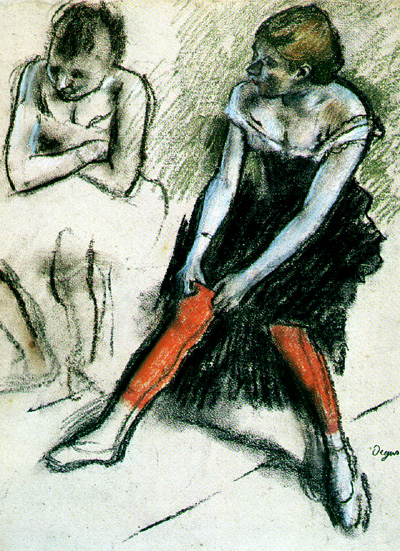

Dancer with Red Stockings, c.1883-85 (Hyde

Collection Art Museum, Glens Falls, NY)

Dancer with Red Stockings, c.1883-85 (Hyde

Collection Art Museum, Glens Falls, NY)