Walking in History

Ruma - earliest pictorial record of Polio

(3,000 BC)

Ruma

was a Syrian boy who probably had the earliest known case of a disease

now known as Polio. When Ruma was 5 years old he got very sick with pain

in his head and his leg ached. When he was no better after several days,

his father carried the boy to the temple where they believed the priest

would cure him with powerful magic (charms, amulets, herbs, and magic drinks).

Ruma

was a Syrian boy who probably had the earliest known case of a disease

now known as Polio. When Ruma was 5 years old he got very sick with pain

in his head and his leg ached. When he was no better after several days,

his father carried the boy to the temple where they believed the priest

would cure him with powerful magic (charms, amulets, herbs, and magic drinks).

The story of Ruma is seen on a 3,000 year old Egyptian tablet, and is

perhaps the earliest pictorial record of Polio. Some thought maybe his

leg was just poorly drawn, but the stone tablet (stele) tells the story

of Ruma, now a grown man with a withered right leg. And, he is holding

a long stick to use as a crutch. The tablet tells that he is a gatekeeper

at the temple of Astarte in Egypt. He is shown with his wife, Ama and his

young son, Ptah-m-heb. He brings with him fruit, wine, and a gazelle for

the goddess he believes saved his life.

"Never to Die: the Egyptians in their own words," by Josephine Mayer

and Tom Prideaux, p. 80

"Polio Pioneers, The Story of the Fight Against Polio" by Dorothy and

Philip Sterling, 1955, p. 9-12

The Polio Stele (limestone with original paintwork) is part of museum

collection at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek,

Dantes Plads

7, Copenhagen, Denmark, and was acquired in Egypt in the 1980s.

King Narmer (3,200 BC)

Mighty stride and powerful gastrocnemius and soleus. Scene from the

ceremonial slate (mudstone) palette of Narmer (the last king of Dynasty

0/ or the first king of Dynasty I) discovered at Hierakonpolis, 25º

N 05'; 32º E 47', by Quibell in 1898.

One of the most amazing things about poliomyelitis is that no epidemic

of it was

noted until seventy-one years ago. Large epidemics of other virus diseases,

such as

smallpox, yellow fever, influenza, and measles, are recorded much farther

back in

history.

Greer Williams, Virus Hunters (1960)

No doubt many scenes which occurred in London during the great plague of

1665

were reenacted in our Long Island andWestchester towns. Under the sway

of

panic people looked with skepticism and suspicion on government health

officers.

The selectmen of many villages, whose doctors were struggling with the

impossible

and failing to stop the epidemic or save the individual case from paralysis,

resorted

to home-made martial law. Deputy sheriffs, hastily appointed and armed

with

shot-guns, patrolled the roads leading in and out of towns, grimly turning

back all

vehicles in which were found children under sixteen years of age. Railways

refused

tickets to these selected youngsters, the innocent victims of ignorance

and despair.

Indeed, the notion was firmly held that below the magic age, called sweet

at other

times, there lurked the dread disease, whereas above it no menace existed

either

for the individual or the community.

George Draper, Infantile Paralysis (1935)

The epidemic of 1916 will go down in history as the high-water mark in

attempts at

enforcement of isolation and quarantine measures.

John R. Paul, A History of Poliomyelitis (1971)

It was not the disease itself, but outbreaks of epidemic proportions

that were of recent origin. An Egyptian stele, dating from

the period 1580-1350 BC and depicting a young man with a withered leg

leaning on a long staff, suggests that polio has been endemic since ancient

times.

The term poliomyelitis derives from the Greek words, polios, meaning `grey',

and myelos,

`matter', and refers to the grey matter of the spinal cord. The disease

was called by many names

in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including: Dental Paralysis,

Infantile Spinal

Paralysis, Teething Paralysis, Essential Paralysis of Children, Regressive

Paralysis, Myelitis of the

Anterior Horns, Tephromyelitis (from the Greek tephros, meaning `ash-grey')

and, most

poetically, Paralysis of the Morning-after the way in which a child goes

to bed apparently

healthy, wakes feverish in the night and then is unable to get up in the

morning. The number of

names ÷ and there were several others ÷ reflects the confusion

over the nature of the disease.

Perhaps the earliest recorded case is that of Sir Walter Scott (born in

Edinburgh in 1771),

who was led to believe that he `showed every sign of health and strength'

till he was about

eighteen months old. Then:

One night, I have been told, I showed great reluctance to be caught and

put to bed,

and after being chased about the room, was apprehended and consigned to

my

dormitory with some difficulty. It was the last time I was to show much

personal

agility. In the morning I was discovered to be affected with the fever

which often

accompanies the cutting of large teeth. It held me three days. On the fourth,

when

they went to bathe me as usual, they discovered that I had lost the power

of my

right leg .... There appeared to be no dislocation or sprain; blisters

and other

topical remedies were applied in vain ...

The impatience of a child soon inclined me to struggle with my infirmity,

and I

began by degrees to stand, to walk, and to run. Although the limb affected

was

much shrunk and contracted, my general health, which was of more importance,

was much strengthened by [my] being frequently in the open air, and, in

a word, I

who in a city had probably been condemned to helpless and hopeless decrepitude,

was now a healthy, high-spirited, and, my lameness apart, a sturdy child

...

The first attempt at a clinical description of the disease was made by

the English physician,

Michael Underwood, in the second edition of his treatise on the Diseases

of Children,

published in 1789. He calls it `Debility of the Lower Extremities' and

writes: `It is not a common

disorder, I believe, and seems to occur seldomer in London than in some

parts. Nor am I

enough acquainted with it to be fully satisfied, either, in regard to the

true cause or seat of the

disease, either from my own observation, or that of others.' Nevertheless,

he is inclined to

attribute it to `teething and foul bowels'. Where both lower extremities

`have been paralytic,

nothing has seemed to do any good but irons to the legs, for the support

of the limbs, and

enabling the patient to walk'. (A later editor of Underwood's treatise,

obviously unfamiliar with

the flaccidity of the paralysis resulting from polio, comments parenthetically:

`If the limbs are

paralytic, how are irons to the legs to enable the patient to walk?')

The first account of an outbreak of the disease was written by a young

doctor

called John Badham, the son of a distinguished professor of medicine at

the

University of Glasgow. It took place in 1835 in Worksop, in north

Nottinghamshire. There were four cases, described by Badham in meticulous

detail. He comments on the `extraordinary youth' of all four patients;

on the

`cerebral symptoms', such as drowsiness or abnormality of the pupils of

the eye; on

the `remarkable [fact] that in no one instance has the health of the child

been in any

degree impaired'; and on the strabismus (squinting) apparent in one case,

leading

him `to suspect a cerebral complication, rather than a spinal one'. Unfortunately,

the

thirty-two-year-old John Badham died of consumption in 1840, the very year

in

which the first systematic investigation of poliomyelitis, written partly

in response to

his account of the Worksop outbreak, was published in Germany.

Like Badham, Jacob von Heine draws attention both to the extreme youth

of patients (six

months to three years) and to their good general health (though he is referring

to their health

preceding the attack). But where Badham sees only `drowsiness', Heine recognises

fever and

pain in children during the pre-paralytic phase of the illness, which makes

him think that the

disease may be contagious, and far from suspecting `a cerebral complication,

rather than a spinal

one', he finds no cerebral involvement and concludes that all the symptoms

`point to an affection

of the central nervous system, namely the spinal cord'.

In the matter of treatment (which had baffled Badham), Heine steered clear

of fashionable

nostrums such as purges, emetics, blisters and bleedings, and recommended

`exercise, baths,

and various simple surgical procedures, followed by the application of

braces and apparatus'. As

the historian of the disease and a leading participant in its `conquest',

Dr John R. Paul of Yale

University points out, `Considering the degree to which the handling of

a given disease is wont to

change over a period of 125 years, Heine's treatment of paralyzed limbs

and the resulting

deformities and disabilities of children has undergone remarkably little

alteration.'

In 1907 the Swedish paediatrician, Ivar Wickman, named the disease `Heine-Medin

disease'

after both the great German orthopaedist and the Swedish pioneer, Karl

Oskar Medin, whose

pupil Wickman was. Medin's involvement in an unprecedented outbreak of

forty-four cases in

Stockholm in 1887 led him to categorise various types of the disease ÷

spinal, bulbar, ataxic,

encephalitic and polyneuritic ÷ as well as, crucially, to conclude

that its acute phase consisted of

two separate fevers, sometimes with a fever-free remission (what the American

doctor George

Draper mis-labelled the `dromedary form' ÷ it is the Bactrian camel,

not the dromedary, that

has two humps). The initial fever was no more than a general malaise; it

was the second attack

that did the damage to the central nervous system.

The significance of this finding was not lost on the young Ivar Wickman

when he came to

investigate the infinitely more serious Scandinavian epidemic of 1905,

in which there were more

than 1,000 cases. The questions that concerned him were: was the disease

contagious and, if so,

how was it spread ÷ by direct contact with infected children, or

by carriers of the virus who

themselves showed no sign of infection? Others, including On Charles Caverly

in his notes on the

1894 Vermont outbreak, had observed that there could be `abortive' or non-paralytic

cases.

Wickman's originality lay in suggesting that non-paralytic cases were both

far more widespread

than anyone had supposed and instrumental in spreading the disease. His

experience of the 1905

epidemic convinced him that Heine-Medin disease was highly contagious,

and that apparently

healthy or only mildly affected persons played a key role in spreading

it.

Although he committed suicide at the age of forty-two, just two years before

the New York

epidemic, Wickman's historic monograph of 1907 earned him a place in the

Polio Hall of Fame

erected in 1958 at Warm Springs, Georgia, to celebrate the twentieth anniversary

of the

National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (where fifteen doctors and

scientists are honoured,

along with the founders of the NFIP, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Basil O'Connor).

The end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century was

once considered a

medical golden age, but has recently been dubbed `the Childhood of Scientific

Medicine, a

period of great stimulus and rapid growth, filled with the excitement of

learning new things ÷

and also filled with childish certainties'. Following Robert Koch's painstaking

and brilliant work

on anthrax, tuberculosis and cholera, and Pasteur's discovery of a rabies

vaccine (a century after

Jenner had started the whole business of vaccination by deliberately infecting

people with

cowpox as a preventive of smallpox), `Everybody, everywhere, tried to hunt

microbes, see

them, grow them, identify them, explain them, escape them. Their primary

activity ... was finding

and naming the causes of infectious diseases. It was the Day of Diagnosis.'

The microbes being

so assiduously hunted were largely bacteria, and the essential tackle needed

for their capture

included the microscope, dyes that highlighted the microorganisms, culture

dishes, test tubes and

some unfortunate laboratory animal to act as involuntary host. Bacteriology,

or microbiology,

was the name of this sport; virology had yet to be born.

As far as microbe hunters were concerned, the only difference between bacteria

and viruses

was one of size. Bacteria were the organisms which would not pass through

a porcelain filter;

viruses the ones which would. If the filtration process succeeded in sterilising

cultures of

organisms, then they were bacteria; if not ÷ and laboratory animals

could be reinfected after

filtration of the culture ÷ it was called a virus. Bacteria became

visible under the microscope if

stained with certain types of dye; viruses, however, were too small to

be seen, even through an

optical microscope, and it was practically impossible to study them visually

before the invention

of the electron microscope in 1937.

Despite the virtual invisibility of viruses, immunisation was first discovered

in relation to a virus

÷ smallpox ÷ and the first two human vaccines (the second

being rabies) were virus vaccines.

But as John Rowan Wilson points out, `almost all the really productive

developments in this field

after the death of Pasteur until 1930 were in connection with bacteria.

The reason for this lay in

the technical difficulties of culturing the organisms'. In Vienna in 1908,

Drs Karl Landsteiner and

Erwin Popper discovered that the infectious agent for poliomyelitis was

not a bacterium, but a

`filterable virus' ÷ as any micro-organism that passed through the

porcelain filter came to be

called. When Landsteiner and Popper injected filtered fluid taken from

the spinal cord of a polio

victim into the brains of two monkeys, both animals went down with the

disease. Through their

experiment, the two scientists not only established the cause of polio,

but also set the pattern for

future research, with monkeys as polio's primary `guinea pigs'.

The importance of their discovery was widely recognised, not least by Simon

Flexner in New

York. Flexner had been appointed director of the newly established Rockefeller

Institute for

Medical Research in 1903 and had already successfully developed an antiserum

(serum is the

watery fluid left when blood coagulates and contains proteins called globulins

which comprise

antibodies) for cerebrospinal meningitis. In doing this, he had worked

out one of `only about four

big ideas [needed] in order to prevent human diseases via vaccination'.

The first big idea, at least two thousand years old, is that people who

recover from

certain infectious diseases are safe from a second attack. The second is

that a

scientist can find a suitable animal host, susceptible to the infection,

that will

manufacture virus for him in quantity. The third idea is that in such a

host, or

through some laboratory manoeuvre, the scientist can find a way of taming,

stunning, or killing the virus so that it will still produce disease resistance

but not the

disease. The fourth idea is the use of antibodies in an immune serum ÷

or

antiserum, as it is also called ÷ as a quantitative index for virus

presence. This is

called a virus-neutralization test.

The neutralisation test was originated by George M. Sternberg, a military

doctor who was

promoted to Surgeon General of the US army during Cleveland's presidency.

It was already

known that blood serum contained antitoxic properties in relation to bacteria,

but Sternberg was

the first to show that it was true for viruses, too. Following Sternberg's

÷ and Landsteiner's ÷

lead, Flexner `demonstrated in 1910 that the serum of monkeys convalescent

from experimental

[i.e. artificially induced] poliomyelitis contained antibodies, spoken

of as "germicidal substances"

÷ a finding that was made almost simultaneously by Landsteiner and

others'.

Shortly after this, Netter and Levaditi [in Paris] and others also found

these

neutralizing substances in the blood of humans recovering from poliomyelitis.

This

demonstration of antibodies in convalescent patients was to prove another

landmark in the therapeutic history of the disease. Its significance ranked

almost on

a par with the discovery of the virus, a fact unappreciated until some

years later.

One of several sons of Jewish immigrant parents, Simon Flexner had had

a distinctly unpromising

childhood in Louisville, Kentucky. When he was ten, his father, Morris,

had taken him along to

the local jail as a tacit warning of what lay ahead of him if he did not

mend his ways. But this visit

filled the young Flexner with excitement rather than dread and he surprised

his older brothers,

who had gathered round to gloat over his humiliation, by saying that he

had `had a swell time'.

He left school at fourteen and was apprenticed to a plumber, according

to one historian, who

writes: `At the end of a week the plumber returned him to his father with

the blunt evaluation that

he was too dumb to be a plumber.' It is a good story, perhaps too good,

since Flexner's son tells

it rather differently:

Simon received a curt command to follow his father and was led into a plumber's

shop. Morris pushed the boy forward and offered him to the plumber as an

apprentice. The plumber said he did not need an apprentice. Morris went

out and

walked off, leaving the boy standing on the street.

Whichever version one accepts, there can be no doubt that during his adolescence

Flexner was,

in his own words, `in and out of wretched jobs leading nowhere'. It was

not until he was

apprenticed to a pharmacist that he found a sense of direction. After that,

his rise was meteoric,

through Johns Hopkins Medical School in its heyday and a professorship

of pathology at the

University of Pennsylvania to the Rockefeller Institute, whose first director

he was ÷ a post he

held for more than thirty years. Considering the ÷ perhaps disproportionate

÷ influence he

would have on medical research in the United States over three decades,

it is worth noting that

his initial medical education at the University of Louisville Medical School

was a farce. Flexner

recalls, `I did not learn to practice medicine, indeed, I cannot say that

I was particularly helped

by the school. What it did for me was give me the MD degree.' Appropriately

enough, his own

younger brother, Abraham, was to put an end to such anomalies by exposing

them in his 1910

`Flexner Report' on Medical Education in the United States and Canada.

Simon Flexner's lack of clinical competence and experience, combined with

his belief that

`medicine derived from such basic sciences as pathology, physiology, chemistry,

and

bacteriology', meant that his initial staff appointments to the Rockefeller

Institute `were not of

physicians interested in pursuing problems in clinical medicine, but rather

of investigators skilled

in the basic sciences who sought to cast light on medical problems through

experimental

research'. The success of the institute's experiments with monkeys in developing

the antiserum

for cerebrospinal meningitis, reducing the mortality rate from three in

four to one in four,

convinced Flexner of the validity of his methods and determined his approach

to polio research,

encouraging a degree of confidence which was scarcely justified by subsequent

events.

Initially, however, he succeeded in taking Landsteiner's work a crucial

stage further by

transferring poliovirus not just from humans to monkeys, but from monkey

to monkey. (Others,

including Landsteiner himself, also achieved this, but Flexner did it first.)

When Flexner published

his report, he omitted the word experimental from the title ÷ a

very significant omission,

according to Dr John Paul:

Indeed this was a major mistake that was to dog Flexner's footsteps throughout

his

entire professional life ÷ his failure to distinguish between certain

aspects of

experimental poliomyelitis in the monkey and the disease in man ... It

was an error

with unfortunate implications that were to influence thought at the Rockefeller

Institute for a generation.

Paul compares Flexner's role as `laboratory doctor' unfavourably with the

clinical investigations

of a contemporary Swedish team headed by Carl Kling. Sweden had suffered

another epidemic

in 1911 (at nearly 4,000 cases the largest to date anywhere in the world),

and Kling and his

colleagues succeeded in isolating poliovirus from living patients ÷

not just from those who had

been paralysed, but from abortive cases as well, thus confirming Wickman's

theories about the

way the disease spread. From autopsies they also made important discoveries

of the sites in the

body favoured by the virus other than the central nervous system, where

the damage was done;

as they expected, they found it in the throat, but they were surprised

to find it in the intestinal wall

as well. This caused them to ponder such key questions as how the virus

entered the body and

how, once there, it penetrated the central nervous system. They did not

come up with all the

answers but, by combining clinical and laboratory techniques, at least

they were asking the right

questions.

A news item in the New York Times of 9 March 1911 suggests that Simon Flexner

was so

confident of the rectitude of his approach that he was not looking to the

Swedes or anyone else

for help in solving the mysteries of polio:

The Rockefeller Institute in this city believes that its search for a cure

for infantile

paralysis is about to be rewarded. Within six months, according to Dr Simon

Flexner, definite announcement of a specific remedy may be expected.

`We have already discovered how to prevent the disease,' says Dr Flexner

in a

statement published here today, `and the achievement of a cure, I may

conservatively say, is not now far distant ...'

No cure for polio has ever been achieved and more than forty years would

elapse before a safe

and reliable method of prevention was developed.

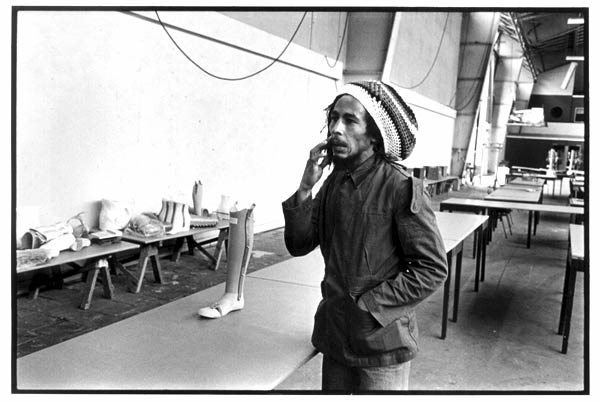

During the 90's Edward Hooper, a British journalist, traveled to Africa

and became convinced that AIDS was an act of man, not an act of God. He

interviewed hundred of participants and collected thousands of documents

to support his theory. The earliest cases of AIDS occurred in central Africa,

in the same regions where Koprowski's vaccine was given to over a million

people in 1957-1960.

Hooper mapped the locations where Koprowski's CHAT vaccine was given

and where the earliest cases of AIDS were discovered. It showed a dramatic

geographical correlation.

Hooper claims that kidneys from chimpanzees infected with SIV were used

to grow the polio virus during Koprowski's 1950's vaccination campaign.

Archival footage confirms that a large number of chimpanzees were housed

at Camp Lindi, located upstream from Koprowski's medical laboratory in

Stanleyville in the former Belgian Congo.

Paul Osterrieth and Hilary Koprowski steadfastly denied that chimpanzee

tissue was used to grow the polio virus in the Congo.

Before his death Pierre Doupagne, the chief technician at the laboratory

of Stanleyville admitted to Edward Hooper that he made sterile tissue culture

from chimps for Paul Osterrieth.

In September 2000 the world's top AIDS specialists assembled at London's

Royal Society for a conference on the origins of AIDS. It was meant to

give Edward Hooper a chance to present his evidence to the scientific community.

From the opening of the conference arguments were launched against Hooper's

theory. Then there was was a surprise announcement. Samples of Kopowski's

CHAT vaccine had been located and tested and found not to have any trace

of HIV, SIV or chimp DNA.

This announcement was viewed by the scientific community as a decisive

statement against Hooper's theory. Articles were published in Nature and

Science concluded that Hooper's hypothesis was not viable.

The Emperor Claudius (reigned 41 - 54AD)

Emperor

Tiberius Claudius Drusus Nero Germanicus was born in 10 BC to Nero Claudius

Drusus and his wife

Emperor

Tiberius Claudius Drusus Nero Germanicus was born in 10 BC to Nero Claudius

Drusus and his wife

Antonia. Although he came from a royal blood

line, his family had a very low opinion of his abilities and often

ignored him. Labeled an invalid from birth

because of physical disabilities including partial paralysis, stammering,

slobbering, and limping, he was the last person

his family thought would inherit the throne and serve as Roman

Emperor. An outcast in his home environment,

Claudius turned to the study of history to occupy his time. He

authored various works about orthographic

reform of the Roman alphabet and a work defending Cicero, a

republican politician and orator. Claudius

also enjoyed playing dice games.

Claudius

escaped the wrath of his mad nephew, Caligula, because the effects of his

infantile paralysis (polio) made him appear as no threat to the throne.

However, after the Praetorian Guard assassinated Caligula and he was thrust

upon the throne, he

Claudius

escaped the wrath of his mad nephew, Caligula, because the effects of his

infantile paralysis (polio) made him appear as no threat to the throne.

However, after the Praetorian Guard assassinated Caligula and he was thrust

upon the throne, he

surprised everyone by being a capable administrator. His major mistake

was recalling Caligula's sister Agrippina back from

banishment and wedding her. She later poisoned him after he adopted

her son Nero, to get her son on the throne.

Claudius' rise to power came after Emperor

Gauis (Caligula), his nephew, was unexpectedly murdered on January

1, AD 41. Claudius became heir to the throne,

to many a Roman's dismay. The soldiers, courtiers, freedman, and

foreigners were his main support although

the senatorial aristocracy also offered to back the new emperor. Many

Romans sought to have Claudius assassinated

because of his cruel and ruthless discussions and actions with

members of the senate and knighthood. It is

thought by some that he even executed senators on occasion. Despite

this conflict Claudius did respect these agencies

and gave new opportunities to them both.

Claudius' reign was marked with an expansion

of the Roman Empire. He invaded and conquered Britain in AD 43

and captured Camulodunum. There he started

a colony of veterans and built client-kingdoms to protect the small

populated land. Claudius also took over North

Africa and annexed Mauretania, where he established two

provinces as well. Around AD 49 he also annexed

Iturea and allowed the province of Syria to control it, trying

not to come into conflict with the Germans

and the Parthians.

In the area of civil administration he encouraged

urbanization. The judicial system improved under his reign and he

favored the modern extension by individual

and collective grants in Noricum. Claudius also made many

administrative innovations. He increased his

control over finances and province administration and gave

jurisdiction of fiscal matters to the governors

under him in the senatorial provinces.

Claudius' personal life was wrought with conflicts

that ultimately led to his undoing. He married three times. His

first wife, Boudicca, started a revolt, and

his second wife had a strong sexual appetite that led her to conspiracy

and ultimately, her execution. Claudius' third

time was not a charm either. He decided to stay within the family and

married his niece, Aggripina. She was very

influential over Claudius to the point where he adopted her son Nero.

Then she fed Claudius a dinner containing

poisonous mushrooms which killed him. Her main motive was that her

precious son, Nero, might inherit the throne.

Although Claudius was generally thought of

as a weak leader and was labeled, even by his own family, as

someone not worthy to rule; he made notable

contributions to the development of the Roman empire. He

conquered and colonized Britain, established

provinces in North Africa, and he urbanized and innovated his civil

administration. He died an unnecessary and

tragic death by a plate of poisonous mushrooms dished out by his scheming,

power-hungry wife.and was succeeded by his adopted son, Nero.

The medical and historical evidence suggest that Claudius was given

mushrooms that contained muscarine, a deadly toxin that

attacks the nervous system, causing a wide range of agonizing symptoms,"

says William A. Valente, M.D., clinical professor of

medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

On October 13, AD 54, Claudius became gravely ill after devouring a

heaping helping of mushrooms served up by his fourth

wife, Agrippina. His symptoms included extreme abdominal pain, vomiting,

diarrhea, excessive salivation, low blood pressure,

and difficulty breathing. Claudius was dead within 12 hours.

So what was Agrippina's motive? "Power," says Richard Talbert, Ph.D.,

who is the William Rand Kenan Professor of History

at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Ambitious and influential,

Agrippina had convinced Claudius to adopt her son

Nero, so that Nero would inherit the throne. But when Agrippina learned

that Claudius might tap his own son for the job,

Agrippina hatched the mushroom murder plot.

Some historians have suggested that Claudius' demise was hastened by

an additional dose of poison administered by his

physician. "That's pure speculation," says Dr. Talbert, who notes that

the historical record is far from complete. While the

weapon of choice was the poisoned mushrooms, Dr. Valente says Claudius

may actually have died of "de una uxore

nimia,"---a Latin phrase meaning "one too many wives."

Some say that Claudius also gives his name to the symptom of intermiittent

claudication, pathognomonic of peripheral vascular disease. He had a limp

together with a tendency to stop walking and grimace as if in pain. The

two words however, are etymologically unrelated. There already existed

a latin word at the time 'claudeo/claudico' which meant to limp, which

seems a rather cruel coincidence for the Emperor. Claudicant first appeared

in the English language in 1624.

Autobiography,

translated by Robert Graves

Tamerlane (1336 - 1405) - The Iron Limper

-

Tamerlane, the name was derived from the Persian Timur-i

lang, "Temur the Lame" by Europeans during the 16th century. His Turkic

name is Timur,

which means 'iron'. In his life time, he has conquered more than anyone

else except for Alexander. His armies crossed Eurasia from Delhi to Moscow,

from the Tien Shan Mountains of Central Asia to the Taurus Mountains in

Anatolia. From 1370 till his death 1405, Temur built a powerful empire

and became the last of great nomadic leaders.

There are abundant ancient sources written about Tamerlane. We have

the primary source from Spanish Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, sent by King Henry

III of Castile on a return embassy to Tamerlane. There is also a Persian

biography of Tamerlane by Ali Sharaf ad-Din and the Arab biography by Ahmad

ibn Arabshah; from Marlowe to Edgar

Allan Poe, he continues to fascinate us as hero or viper.

Timur claimed direct descent from Jenghiz Khan through the house of

Chagatai. He was born at Kesh (the Green city), about fifty miles south

of Sarmarkand in 1336, a son of a lesser chief of the Barlas tribe. Sharaf

ad-Din explained that in his 20s, he received arrow wounds in battle while

stealing sheep in his twenties and left him lame in the right leg and with

a stiff right arm for the rest of his life. But Tamerlane made light of

these disabilities; by 1369 he had possessed himself of all the lands which

had formed the heritage of Chagatai and, after being proclaimed sovereign

at Balkh, made Samarkand his capital.

He was said to be tall strongly built and well proportioned, with

a large head and broad forehead. His complexion was pale and ruddy, his

beard long and his voice full and resonant. Arabshah describes him approaching

seventy, a master politician and military strategist:

steadfast in mind and robust in body, brave and fearless, firm

as rock. He did not care for jesting or lying; wit and trifling pleased

him not; truth, even were it painful, delighted him.....He loved bold and

valiant soldiers, by whose aid he opend the locks of terror, tore men to

pieces like lions, and overturned mountains. He was fautless in strategy,

constant in fortune, firm of purpose and truthful in business.

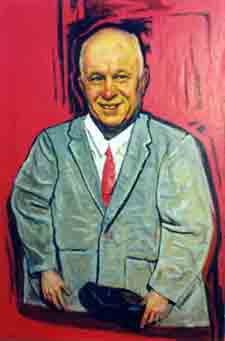

In 1941,

the body of Tamerlane was permitted to be exhumed by a Russian scientist,

M. M. Gerasimov. The scientist found Timur, after examining his skeleton,

a Mongoloid man about 5 feet 8 inches. He also confirmed Tamerlane's lameness.

In his book The Face Finder, Gerasimov explains how he was able

to reconstruct exact likenesses of Timur from a careful consideration of

his skull.

In 1941,

the body of Tamerlane was permitted to be exhumed by a Russian scientist,

M. M. Gerasimov. The scientist found Timur, after examining his skeleton,

a Mongoloid man about 5 feet 8 inches. He also confirmed Tamerlane's lameness.

In his book The Face Finder, Gerasimov explains how he was able

to reconstruct exact likenesses of Timur from a careful consideration of

his skull.

Different sources indicate that Timur is a man with extraordinary intelligence

- not only intuitive, but intellectual. Even though he did not know how

to read or write, he spoke two or three languages including Persian and

Turkic and liked to be read history at mealtimes. He had aesthetic appreciation

in buildings and garden. It has been said that he loved art so much that

he could not help stealing it! The Byzantine palace gates of the Ottoman

capital of Brusa were carried off to Samarkand, where they were much admired

by Clavijo. Ibn Khaldun, who met him outside Damascus in 1401 worte:

"This king Timur is one of the greatest and mightiest kings...he

is hightly intelligent and very perspicacious, addicted to debate and argument

about what he knows and also about what he does not know!"

Known to be a chess player, he had invented a more elaborate form of

the game, now called Tamerlane

Chess, with twice the number of pieces on a board of a hundred and

ten squares.

The same as Jenghiz Khan, Timur rose from a nomad ruler; however unlike

Jenghiz Khan, he was the first one based his strength on the exploitation

of settled populations and inherited a system of rule which could encompass

both settled and nomad populations. Those who saw Timur's army described

it as a huge conglomeration of different peoples - nomad and settled, Muslims

and Christians, Turks, Tajiks, Arabs, Georgians and Indians. Timur's conquests

were extraordinary not only for their extent and their success, but also

for their ferocity and massacres. The war machine was composed of 'tumen',

military units of a 10,000 in the conquered territories. It consisted of

his family, loyal tribes particularly the Barlas and Jalayir tribes, recruited

soldiers from nomadic population from as far as the Moghuls, Golden Horde

and Anatolia, and finally Persian- speaking sedentarists.

Timur and his army were never at rest and neither age nor increasing

infirmity could halt his growing ambitions. In 1391 Timur's army fought

and won in the great battle of Kanduzcha on June 18. Following his campaign

in India, he acquired an elephant corps and took them back to Samarkand

for building mosques and tombs. He led the attack and victory on the Ottoman

army in the battle of Ankara on July 28 1402.

With great interest in trade, Timur had a grand plan to reactivate the

Silk Road, the central land route, and make it the monopoly link between

Europe and China. Monopolization was to be achieved by war: primarily,

against the Golden Horde, the master of principal rival, the northern land

route; secondarily, against the states of western Persia and the Moghuls

to the east in order to place the Silk Road under unified control politically;

and finally agaist India, Egypt and China.

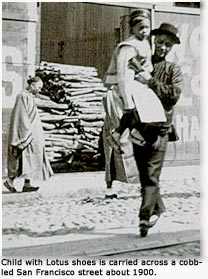

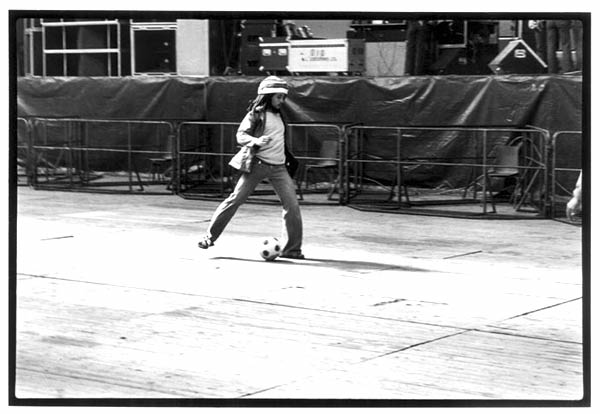

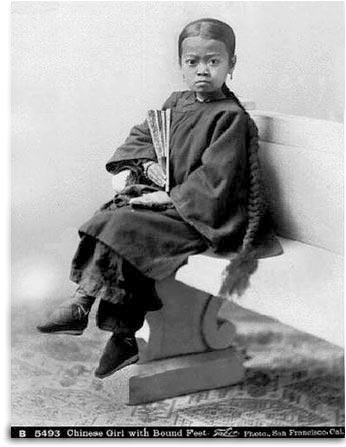

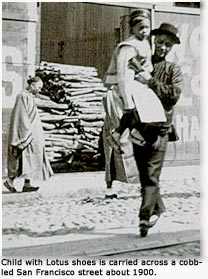

The

Chinese custom of foot binding is another curious reminder of the relationship

between the foot and sex. Strapping of the foot with means of tight bandages

over a period of two or three years was needed to engender the desired

effect. Traditionally, foot-binding began between the ages of five and

seven. Pain was most severe during the first year but gradually diminished.

During the binding the girl at night lay across the bed, putting her legs

on the edge of the bedstead in such a manner as to make pressure under

the knees, thus numbing the parts below. The feet were unbound only once

a month, and the foot was often found gangrenous and ulcerated, with one

or two toes not infrequently being lost. The aim of the ordeal was to produce

a ãthree-inch golden lotusä. The practice, began in the Tang

Dynasty (923-936 AD), continued until the communist era: a 1997 UC San

Francisco study of women over 70 in Beijing found 50% had bound foot deformities.

In 1998, the Xinhua News Agency announced that the Zhiqiang Shoe Factory,

the last to manufacture shoes for bound-feet women would henceforth only

make them on a special-order basis. The factory had added small shoes for

old women to its product range in 1991 to fill a gap in the market, which

was at that time focused on high-heeled shoes.

The

Chinese custom of foot binding is another curious reminder of the relationship

between the foot and sex. Strapping of the foot with means of tight bandages

over a period of two or three years was needed to engender the desired

effect. Traditionally, foot-binding began between the ages of five and

seven. Pain was most severe during the first year but gradually diminished.

During the binding the girl at night lay across the bed, putting her legs

on the edge of the bedstead in such a manner as to make pressure under

the knees, thus numbing the parts below. The feet were unbound only once

a month, and the foot was often found gangrenous and ulcerated, with one

or two toes not infrequently being lost. The aim of the ordeal was to produce

a ãthree-inch golden lotusä. The practice, began in the Tang

Dynasty (923-936 AD), continued until the communist era: a 1997 UC San

Francisco study of women over 70 in Beijing found 50% had bound foot deformities.

In 1998, the Xinhua News Agency announced that the Zhiqiang Shoe Factory,

the last to manufacture shoes for bound-feet women would henceforth only

make them on a special-order basis. The factory had added small shoes for

old women to its product range in 1991 to fill a gap in the market, which

was at that time focused on high-heeled shoes.

Walking in military history

According to the historian Mary Mosher Flesher, a research associate at

Smith College in

Northampton, Massachusetts, locomotion research was the key to

military success in the

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Soldiers of that era could

no longer afford to fling

themselves at one another in a furious melee, Flesher points

out in a recent paper in Annals

of Science. Thanks to the invention of muskets, foot soldiers

could now pick off cavalry from

a distance, and battles were decided by marching speed and rate

of fire. "An

eighteenth-century battle was like a chess game," Flesher says.

"The armies didn't always

want to meet and fight. They were trying to get around each other,

to establish positions as

quickly as possible."

Rather than waste time aiming their inaccurate muskets, soldiers

formed tight ranks, shot in

the general direction of the enemy and then dropped back to reload

while the row behind

them advanced. To help soldiers carry out all those actions as

efficiently as possible, an

empirical military science of marching was developed.

Marching theory, Flesher writes, treated a regiment as a mechanical

system, carefully

quantifying the length and cadence of each soldier's step and

the movement of bodies

through space. The first musket drills were developed by the

Dutch in the late sixteenth

century, but they reached an apex of precision among the Prussians

of the mid-eighteenth

century. On the basis of battlefield observations, Frederick

the Great's soldiers were taught

to stand erect yet relaxed and to swing their legs stiffly as

they marched. To synchronize

their movements they stamped their heels on the ground and clapped

their gun barrels in

unison, while drill sergeants timed their steps with stopwatches.

Prussian martinets are a modern-day caricature. But they were

once a military wonder. "The

more I read about them, the more I marvel at how much they knew,"

Flesher says. "Frederick

was able to increase the marching rate from six to twelve miles

a day. His troops could cross

the battlefield obliquely, in step, while their foes were still

moving at right angles." In 1763,

when the Prussians defeated France and its allies in the Seven

Years' War, they owed their

triumph, in part, to better walking. As a result, the single-mindedness

and discipline of

military drills became a blueprint for everything from manliness

to philosophy to political

authority in Prussia.

Marching theory had many of the earmarks of objective research: it was

precise and its

results were reproducible; it was rigorously tested and continually

reexamined. But it took

civilians to create a true science of locomotion--one that applied

to more than just the

battlefield. Beginning in the 1820s, Eduard, Wilhelm and Ernst

Heinrich Weber, three German

brothers with backgrounds in physiology, anatomy and mechanics,

established the world's

first movement laboratory. The Webers used Hanoverian soldiers

as subjects, but they tried

to make the soldiers forget their training: they wanted to study

natural walking, not

marching. In their 1836 book, Mechanics of the Human Walking

Apparatus, the Webers

described the undulations of the spine, the inclination of the

pelvis and the effects of wind

and gravity on the body. Their conclusion--that the body's natural

gait is more efficient than

marching in most situations--brought walking science full circle.

By the early nineteenth century, in any case, precise marching

had lost some of its military

value. Guns had become more accurate and easier to load, and

so soldiers were advised to

take time to aim. Massive regiments had become easy targets.

Skirmishing was now the

order of the day, and Native American hunters were the new model

soldiers. The Webers'

defense of natural walking, in other words, fit the times perfectly.

The Age of Reason, with

its perfectly ordered armies, had given way to the romantic age,

with its emphasis on

individualism, improvisation and feel for terrain. Locomotion

research would gradually fade to

the background, into biomechanics and orthopedics labs, no longer

destined to turn the tides

of war.

Science World Jan-Feb, 1998

Mary Mosher Flesher (1997) Repetitive order and the human walking apparatus:

Prussian military science versus the Webers' locomotion research Annals

of Science 54 (5) 463-487.

Discalced

(Lat. dis, without, and calceus, shoe).

A term applied to those religious congregations of men and women, the

members of which go entirely unshod or wear sandals, with or without other

covering for the feet. These congregations are often distinguished of this

account from other branches of the same order. The custom of going unshod

was introduced into the West by St.

Francis of Assissi for men and St.

Clare for women. After the various modificiations of the Rule of St.

Francis, the Observantines adhered to the primitative custom of going unshod,

and in this they were followed by the Minims and Capuchins. The Discalced

Franciscans or Alcantarines, who prior to 1897 formed a distinct branch

of the Franciscan Order went without footwear of any kind. The followers

of St. Clare at first went barefoot, but later came to wear sandals and

even shoes. The Colettines and Capuchin Sisters returned to the use of

sandals. Sandals were also adopted by the Camaldolese monks of the Congregation

of Monte Corona (1522), the Maronite Catholic monks, the Poor Hermits of

St. Jerome of the Congregation of Bl. Peter of Pisa, the Augustinians of

Thomas of Jesus (1532), the Barefooted Servites (1593), the Discalced Carmelites

(1568), the Feuillants (Cistercians, 1575), Trinitarians

(1594), Mercedarians

(1604), and the Passionists. (See FRIARS MINOR)

STEPHEN M. DONOVAN

Transcribed by Christine J. Murray

Pace Sticks

The Royal Regiment of Artillery (UK) claim to be the originator of the

pace stick. It was used by field gun teams to ensure correct distances

between the guns. This pace stick was more like a walking stick, with a

silver or ivory knob. It could not be manipulated as the more usual pace

sticks, as it was opened like a pair of callipers. Th stick was later developed

as an aid to drill. In 1928, the late Arthur Brand MVO MBE developed a

drill for pace sticks. The stick that he used is still kept in the Warrant

Officers and Sergeants mess at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.

In 1952 the

Academy Sergeant Major (the late John Lord MVO MBE) started a ãpace

sticking competitionä. This competition was held annually between

Royal Military Academy Sandhurst and the Guards Depot. It was originally

four Sergeants in the team and a Warrant officer as the team captain who

acted as the driver and gave the words of command over the course

which involved marching in slow and quick time whilst alternating turning

the stick with the left or right hand. The teams are now modified to a

frontage of three Sergeants but the driver still remains a Warrant Officer.

Since the closing of the Guards Depot in April 1993 the annual competition

has demised, however the All Arms (World Championships) pace sticking competition

still carries on and is held annually at Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.

Teams from all over the world compete in different categories for the title

of World Champion Pace Sticking team or the prestigious individual World

Pace Stick Champion.

In 1952 the

Academy Sergeant Major (the late John Lord MVO MBE) started a ãpace

sticking competitionä. This competition was held annually between

Royal Military Academy Sandhurst and the Guards Depot. It was originally

four Sergeants in the team and a Warrant officer as the team captain who

acted as the driver and gave the words of command over the course

which involved marching in slow and quick time whilst alternating turning

the stick with the left or right hand. The teams are now modified to a

frontage of three Sergeants but the driver still remains a Warrant Officer.

Since the closing of the Guards Depot in April 1993 the annual competition

has demised, however the All Arms (World Championships) pace sticking competition

still carries on and is held annually at Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.

Teams from all over the world compete in different categories for the title

of World Champion Pace Sticking team or the prestigious individual World

Pace Stick Champion.

Military Stride Length & Cadence

|

Speed

|

Steps per minute

|

Distance

per minute |

Step Length

|

| Slow |

75 |

62 yds 18 ins |

30" |

| Quick |

110 |

91 yds 24 ins |

30" |

| Double |

150 |

150 yds |

36" |

| Side |

Quick time |

- |

10" |

| Stepping out |

Slow or Quick

time |

- |

33" |

| Stepping short |

Slow or Quick

time |

- |

10" |

| Side pace to

clear or cover another (as in forming four deep) |

- |

- |

21" |

In order to beat the time correctly on a drum the "Plummet" must be

used. A variety of pendulums or plummets have been constructed for this

purpose. When none of these can be procured, the following simple method

can be adopted. Suspend a spherical ball of metal by a string that is not

liable to stretch; the length of the string measured from the point of

suspension to the centre of the ball, must be as follows for the different

degrees of march. Thus arranged, the plummet will swing the exact time

required.

|

Inches |

Hundreths |

| Slow time |

24 |

96 |

| Quick |

11 |

66 |

| Double |

6 |

26 |

In comparison to the 120 steps/minute pace of other French units, the

Foreign Legion has an 88 steps/minute marching pace. This can be seen at

ceremonial parades and public displays attended by the Legion, particularly

while parading in Paris on 14 July (Bastille Day). Because of the impressively

slow pace, which Legionnaires refer to as the "crawl", the Legion is always

the last unit marching in any parade. The Legion is normally accompanied

by its own band which traditionally plays the march of any one of the regiments

comprising the Legion, except that of the unit actually on parade. The

regimental song of each unit and "Le Boudin" (commonly called the blood

sausage or black pudding song) is sung by Legionnaires standing at attention.

Also, because the Legion must always stay together, it doesn't break formation

into two when approaching the presidential grandstand, as other French

military units do, in order to preserve the unity of the Legion.

Contrary to popular belief, the adoption of the Legion's slow marching

speed was not due to a need to preserve energy and fluids during long marches

under the hot Algerian sun. Its exact origins are somewhat unclear, but

the official explanation is that although the pace regulation does not

seem to have been instituted before 1945, it hails back to the slow, majestic

marching pace of the Ancien Régime, and its reintroduction was a

"return to traditional roots".

Calvin Coolidge's son

On 30 June 1924, Coolidge's two sons, John and Calvin Jr., set out to play

tennis on the White House tennis court. 16-year-old Calvin Jr., in a hurry

to get out on the court, donned tennis shoes but no socks. Young Calvin's

sockless exertions raised a blister on one of the toes on his right foot.

He didn't tell anyone, and it soon became infected. The next day, the 16-year-old

awoke with a stiff and painful leg. The doctor was called, and his examination

revealed that a septic infection had spread to Calvin's bloodstream and

throughout his body. In 1924, penicillin and other revolutionary infection-fighting

drugs were yet to be discovered, and Calvin's condition was critical. During

the next several days, seven doctors tried stomach washings, blood transfusions,

an operation, and other methods in desperate efforts to save the teenager.

But Calvin only grew weaker. By July 7, he was delirious. Finally, his

body began to relax. He said weakly, "I surrender," and lapsed into a coma.

Four hours later, at 10:30 p.m., he died. President Coolidge blamed himself

for his son's death, and many have claimed that it plunged him into a depression

from which he never recovered.

The strange death of such a prominent young man naturally attracted

the attention of the nation. Before long a rumor began circulating (particularly

among teenagers) that Calvin Jr.'s death was caused by the dye from his

black socks entering his bloodstream through a cut and poisoning him.

How this rumor began is something we can only guess at, and no obvious

explanations spring to mind. Obviously the public knew that whatever killed

Calvin had something to do with a wound on his foot and blood poisoning,

so perhaps the sock rumor arose because it seemed like a logical explanation

to those who were not privy to the details of his injury. Or perhaps, as

Morgan and Tucker suggest, it may simply have been "the result of youthful

anxiety about dress and appearance." Either way, the rumor may have seemed

plausible at the time because some of the coloring agents commonly used

by the clothing industry (such as zinc chloride, which was used to give

socks a pearl gray color, and aniline dye, which was used to make shoe

leather black) did indeed often cause serious inflammations when the unabsorbed

chemicals came into contact with a wearer's skin.

There appears to be a higher than average rate of divorce, alcoholism,

and premature death among the lives of children of U.S. Presidents.

Doug Wead (2002) All The Presidents' Children, Atria Books

John Tyler (President of USA, 1841·1845)

While a 30 year old Congressman in Washington, Tyler developed an

illness that remains difficult to diagnose. Based on Tyler's clear description

of the illness it would today be described as a symmetric, generalized,

subacute paralysis. His recovery was so slow and prolonged that he resigned

from Congress for two years.

Tyler described the illness to his doctor as follows:

I sustained a violent singular shock four days ago. I had gone to the house

on Thursday morning before experiencing a

disagreeable sensation in my head, which increased so much as to force

me to leave the hall. It then visited in succession hands,

feet, tongue, and lips, creating in each the effect that is produced by

what is commonly called a sleeping hand, which all of us are

subject to; but it was so severe as to render my limbs, tongue, and so

forth, almost useless to me. I was bled and took purgatives

which have rendered me convalescent. The doctor ascribed it to a diseased

stomach, and very probably correctly did so. I am

now walking about and I'm to all appearances well, but often experience

a glow in my face and over the whole system which is

often followed by debility with pain in my neck and arms.

Possible diagnoses include Guillain-Barre syndrome, myasthenia gravis,

tick paralysis, diphtheritic paralysis, and botulism

Bumgarner, John R. The Health of the Presidents: The 41 United States

Presidents Through 1993 from a Physician's Point of View. Jefferson, NC:

MacFarland & Company, 1994. ISBN 0-89950-956-8 [a] p. 64

[b] pp. 64-65 [c] p. 65

Dr. Samuel Mudd

and John Wilkes Booth's leg fracture

After

he shot President Abraham Lincoln, John Wilkes Booth broke his left leg

in his leap to the stage at Ford's Theatre. Needing a doctor's assistance,

he and David Herold arrived at Dr. Mudd's (about 30 miles from Washington)

at approximately 4:00 A.M. on April 15, 1865. Dr. Mudd set, splinted, and

bandaged the broken leg (a fracture of the tibia & fibula 3 inches

above the ankle joint). The National Park Service photograph to the right

shows Booth's boot which Dr. Mudd removed when he treated the leg. Although

he had met Booth on at least three prior occasions, Dr. Mudd said he did

not recognize his patient. He said the two used the names "Tyson" and "Henston."

Booth and Herold stayed at the Mudd residence until the next afternoon

(roughly a 12 hour stay). Mudd asked his handyman, John Best, to make a

pair of rough crutches for Booth. Mudd was paid $25 for his services. Booth

and Herold left in the direction of Zekiah Swamp.

After

he shot President Abraham Lincoln, John Wilkes Booth broke his left leg

in his leap to the stage at Ford's Theatre. Needing a doctor's assistance,

he and David Herold arrived at Dr. Mudd's (about 30 miles from Washington)

at approximately 4:00 A.M. on April 15, 1865. Dr. Mudd set, splinted, and

bandaged the broken leg (a fracture of the tibia & fibula 3 inches

above the ankle joint). The National Park Service photograph to the right

shows Booth's boot which Dr. Mudd removed when he treated the leg. Although

he had met Booth on at least three prior occasions, Dr. Mudd said he did

not recognize his patient. He said the two used the names "Tyson" and "Henston."

Booth and Herold stayed at the Mudd residence until the next afternoon

(roughly a 12 hour stay). Mudd asked his handyman, John Best, to make a

pair of rough crutches for Booth. Mudd was paid $25 for his services. Booth

and Herold left in the direction of Zekiah Swamp.

Within days Dr. Mudd was under arrest by the United States Government.

He was charged with conspiracy and with harboring Booth and Herold during

their escape. He went on trial along with Lewis Powell (Paine), George

Atzerodt, Mary Surratt, David Herold, Ned Spangler, Samuel Arnold, and

Michael O'Laughlen. In court witnesses described Dr. Mudd as the most attentive

of the accused. He was dressed in a black suit with a clean white shirt.

Testimony against the doctor at the trial included his harsh treatment

of some of his slaves. He shot one male slave (who survived). New information

regarding Dr. Mudd surfaced in 1977. A previously unknown statement by

conspirator George Atzerodt indicated that John Wilkes Booth had sent liquor

and provisions to Dr. Mudd's home two weeks prior to the assassination.

Like the other defendants, Dr. Mudd was found guilty. His sentence: life

imprisonment. He missed the death penalty by one vote.

Early in 1869

a courier from the United States Government knocked on the front door of

the Mudd farm. When Mrs. Mudd answered, the man handed her an envelope

and said, "From the President of the United States. Please sign this receipt

to certify that I have delivered it to you. If you have a reply, I shall

return it for you." Mrs. Mudd opened the envelope and found a letter written

on White House stationery. It read:

Early in 1869

a courier from the United States Government knocked on the front door of

the Mudd farm. When Mrs. Mudd answered, the man handed her an envelope

and said, "From the President of the United States. Please sign this receipt

to certify that I have delivered it to you. If you have a reply, I shall

return it for you." Mrs. Mudd opened the envelope and found a letter written

on White House stationery. It read:

Dear Mrs.

Mudd: As promised, I have drawn up a pardon for your husband, Dr. Samuel

A.

Mudd. Please

come to my office at your earliest convenience. I wish to sign it in your

presence

and give it to you personally.

Sincerely,

ANDREW JOHNSON

President

of the United States of America.

Mrs. Mudd went to the White House the next morning. There the President

signed and delivered to her the papers for

the release of her husband. The date of the pardon was February 8,

1869.

Dr. Mudd was released from Ft. Jefferson on March 8 and arrived home

on March 20. He had served somewhat less than

4 years in prison. He partially regained his medical practice and lived

a quiet life on the farm.

Dr.

Mudd's father passed away in 1877. In January of 1878 Dr. Mudd's youngest

daughter and ninth child, Nettie, was

Dr.

Mudd's father passed away in 1877. In January of 1878 Dr. Mudd's youngest

daughter and ninth child, Nettie, was

born. In January of 1883 Dr. Mudd had a busy schedule with many sick

patients during a harsh winter. On New Year's

Day he put on his muffler and overshoes and called on patients. He

came down with a severe cold. He was running a

fever and had to remain in bed. As the days progressed, the fever rose.

On January 10th, 1883, Dr. Mudd died of

pneumonia or pleurisy at the age of 49. He was buried in St. Mary's

cemetery next to the Bryantown church where he

first met Booth in 1864. Sarah Frances, who was buried next to him,

lived until November 29, 1911. Dr. Mudd's

descendants, most notably Dr. Richard Mudd (1901-2002) of Saginaw,

Michigan, worked indefatigably to clear his name

of any complicity with John Wilkes Booth. Recently a petition (petitioner

Richard D. Mudd, M.D.) was filed in the United

States District Court for the District of Columbia (case No. 1:97CVO2946)

bringing suit against the Secretary of the Army,

Togo West et.al., ordering the Archivist of the United States to "...correct

the records in his possession by showing that

Dr. (Samuel A.) Mudd's conviction was set aside pursuant to action

taken under 10 U.S.C. sec. 1552.", and that the court

"...order the payment of Petitioner's costs in bringing this action;..."

On July 22, 1998, U.S. District Judge Paul Friedman

said he would rule soon, and on Thursday, October 29, 1998, he ordered

the Army to reconsider the conviction of Dr.

Mudd. Friedman said the Army's recent rulings (see below) against the

request were arbitrary. The following decision

was announced on March 9, 2000: SAGINAW, Mich. (AP) - The U.S. Army

has rejected an appeal to overturn the 1865

conviction of Dr. Samuel Mudd as an accomplice in the escape of John

Wilkes Booth after the Lincoln assassination.

Mudd's 99-year-old grandson, Dr. Richard Mudd of Saginaw, has waged

a long campaign to clear his grandfather's

name. But this week, Army Assistant Secretary Patrick T. Henry rejected

the latest request to throw out Samuel Mudd's

conviction by a military court. Henry said his decision was based on

a narrow question - whether a military court had

jurisdiction to try Samuel Mudd, who was a civilian. "I find that the

charges against Dr. Mudd (i.e., that he aided and

abetted President Lincoln's assassins) constituted a military offense,

rendering Dr. Mudd accountable for his conduct to

military authorities," he wrote in Monday's decision.

On March 14, 2001, Judge Friedman rejected Richard Mudd's contention

that his grandfather should not have been tried

by a military court because he was a citizen of Maryland, a state that

did not secede from the Union, and thus entitled to

a civil trial. John McHale, a Mudd family spokesman, said that an appeal

of Judge Friedman’s ruling would be filed. On

Friday, November 8, 2002, a federal

appeals court dismissed the case. Judge Harry Edwards wrote that the

law under

which the Mudd family was seeking to have Samuel Mudd's conspiracy

conviction expunged applied only to records

involving members of the military. Although Mudd was tried by a military

tribunal, he was not a member of the military.

Dr. Mudd, when under arrest for alleged complicity in Lincoln's murder,

had described Booth's

leg injury as "a straight fracture of the tibia about two inches above

the ankle. There was nothing resembling a compound fracture."(39)

In his letter to Secretary Stanton after the autopsy on Montauk, the Army

Surgeon General had stated that "the left leg and foot were encased

in an appliance of splints and bandages, upon the removal of which, a fracture

of the fibula (small bone of the leg) 3 inches above the ankle joint, accompanied

by considerable ecchymosis, was discovered."(40) In Montauk's pilothouse

that sultry April Thursday no questions had been asked about the leg. However,

shortly before his death in 1891 Dr. May composed a memoir in which

he attributed his identification of the body to "my mark. . .unmistakably

found by me upon it. Never in a human had a greater change taken

place. . .every vestige of resemblance to the living man had disappeared.

But the mark of the scalpel during life remained indelible in death"

settling once and for all "the identity of the man who had assassinated

the President." And the leg? "The right limb was greatly contused,

and perfectly black from a fracture of one of the long bones. . . ."

John Wilkes Booth's autopsy was performed aboard the Montauk by Surgeon

General Joseph K. Barnes and Dr. Joseph

Janvier Woodward. On April 27, 1865, Dr. Barnes wrote the following

account to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton:

Sir,

I have the honor to report that in compliance

with your orders, assisted by Dr. Woodward, USA, I made at 2 PM

this day, a postmortem examination of the

body of J. Wilkes Booth, lying on board the Monitor Montauk off

the Navy Yard.

The left leg and foot were encased in an

appliance of splints and bandages, upon the removal of which, a

fracture of the fibula (small bone of the

leg) 3 inches above the ankle joint, accompanied by considerable

ecchymosis, was discovered.

The cause of death was a gun shot wound

in the neck - the ball entering just behind the sterno-cleido muscle -

2 1/2 inches above the clavicle - passing

through the bony bridge of fourth and fifth cervical vertebrae -

severing the spinal chord (sic) and passing

out through the body of the sterno-cleido of right side, 3 inches

above the clavicle.

Paralysis of the entire body was immediate,

and all the horrors of consciousness of suffering and death must

have been present to the assassin during

the two hours he lingered.

Dr. Woodward wrote the following detailed account of his autopsy

on John Wilkes Booth:

Case JWB: Was killed April 26, 1865, by a conoidal

pistol ball, fired at the distance of a few yards, from a

cavalry revolver. The missile perforated the

base of the right lamina of the 4th lumbar vertebra, fracturing it

longitudinally and separating it by a fissure

from the spinous process, at the same time fracturing the 5th

vertebra through its pedicle, and involving

that transverse process. The projectile then transversed the spinal

canal almost horizontally but with a slight

inclination downward and backward, perforating the cord which

was found much torn and discolored with blood

(see Specimen 4087 Sect. I AMM). The ball then shattered the

bases of the left 4th and 5th laminae, driving

bony fragments among the muscles, and made its exit at the left

side of the neck, nearly opposite the point

of entrance. It avoided the 2nd and 3rd cervical nerves. These facts

were determined at autopsy which was made

on April 28. Immediately after the reception of the injury, there

was very general paralysis. The phrenic nerves

performed

their function, but the respiration was

diaphragmatic, of course, labored and slow.

Deglutition was impracticable, and one or two attempts at

articulation were unintelligible. Death, from

asphyxia, took place about two hours after the reception of the

injury.

Break a leg?

Although the Wilkes Booth story has been used to explain the Theater phrase

"Break a leg", the most plausible story behind holds that it originated

in twentieth-century Germany. Lexicographers believe the phrase comes from

the German Halsund Beinbruch (roughly, "break your neck and leg"), a phrase

first heard during World War I. Halsund Beinbruch was used in the Luftwaffe

as a way of saying happy landings, and it's still used in the theater and

among skiers.

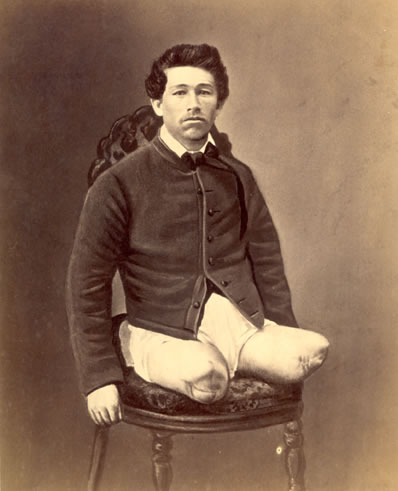

American

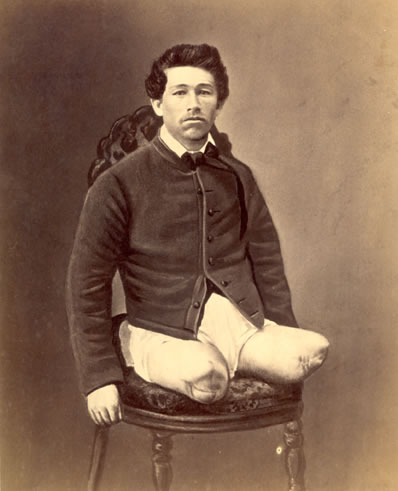

Civil War Prosthetics: The Gettysburg Limb

In 1866, North Carolina became the first state to start a program

to give artificial limbs to thousands of amputees after the war.

The program offered free rail passage and rooming in Raleigh

to veterans who came to the city to have limbs fitted. The state paid $75

to those who didn't want an artificial leg or wanted to buy a different

model, and $50 to those who didn't want an artificial arm. In all, 1,550

veterans wrote to the state about their wartime disabilities.

Hanna, the peg-leg whittler -- like his grandson 137 years later --

thought the store-bought leg was something special. It was, Wegner says,

"his Sunday-go-to-meeting leg." Hanna, a native of Anson County, was a

member of the 26th North Carolina Regiment, a regiment that lost more soldiers

than any other on either side in the Civil War.

At Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, he was shot above the left ankle and

in the head. Surgeons removed the grapeshot from his head and amputated

his leg just below the knee. With arm and leg wounds, "They didn't take

shot out back then. They just whacked it off," said Hanna's grandson, Duncan

Hanna.

There was broad public support for the artificial-limb program, said

Ansley Herring Wegner, a researcher at the N.C. Division of Archives and

History. The state spent $81,310.12 on the program between 1866 to 1870,

she said. In 1872, the combined state and local budgets for public schools

was $155,000, according to state records. She has written a book on the

leg program titled "Phantom Pain" that will be published this summer.

Hanna agreed to lend his grandfather's leg to the state. After candy

wrappers, a dime and even a baby tooth were removed from inside, the leg

underwent some restoration work. It is now on display in a case at the

Bentonville Battlefield - next to the blades in a Civil War surgeon's amputation

kit.

"He liked to be sharp. He wouldn't wear it in the rain, either - not

even with a boot on it," he said. Robert Hanna struggled at times, especially

in the fall, when the corn stalks on his farm were dry. "You could hear

him screaming, and they'd say, 'Leave him alone,' " his grandson said.

"The wind would blow and the corn stalks would rub together and it would

sound like men marching. He'd have flashbacks." "He had one that had a

bull's hoof on it (for the foot)," his grandson said. Robert Hanna continued

using the state-issued leg sparingly until he died in 1918, still a proud

Confederate veteran.

"He was buried with no leg. He was buried in a gray uniform -

a gray suit they made for him. He wouldn't wear a blue suit," his grandson

said.

Although

fortunate to be unconscious during surgery, soldiers who underwent the

knife often received a nasty visitor a few days later-infection. Any open

wound almost always became infected. The unwashed hands of the surgeon,

the non-sterile surgical instruments used on a succession of men, and the

dirty sponges used on an entire ward of wounded soldiers all introduced

infectious bacteria into wounds. These infections often resulted in gangrene

and death.

Although

fortunate to be unconscious during surgery, soldiers who underwent the

knife often received a nasty visitor a few days later-infection. Any open

wound almost always became infected. The unwashed hands of the surgeon,

the non-sterile surgical instruments used on a succession of men, and the

dirty sponges used on an entire ward of wounded soldiers all introduced

infectious bacteria into wounds. These infections often resulted in gangrene

and death.

Case of Private Julius Fabry

Private Julius Fabry, K Company,

4th U.S. Artillery, age 38, was shot in the left knee at the battle of

Deep Bottom, Virginia, on Aug.16, 1864. His leg was amputated just above

the knee on the following day. The thigh bone became infected and Fabry's

pain was treated with morphine for the next 6 years. Pus drained regularly

from the infected bone. In 1870, the infected bone was remove at the hip

joint. In 1878, Fabry reported no trouble with the stump, but he was unwilling

to use an artificial limb. Fabry died in 1894.

Amputation

Surgeons

frequently treated arm and leg wounds by amputating. The grisly wounds

caused by bullets and schrapnel were often contaminated by clothing and

other debris. Cleaning such a wound was time-consuming and often ineffective.

However, amputation made a complex wound simple. Surgical manuals taught

that an amputation should be performed within the first two days following

injury. The death rate from these so-called primary amputations was lower

than the rate for amputations performed after the wound became infected.

Union surgeons performed nearly 30,000 amputations.

Surgeons

frequently treated arm and leg wounds by amputating. The grisly wounds

caused by bullets and schrapnel were often contaminated by clothing and

other debris. Cleaning such a wound was time-consuming and often ineffective.

However, amputation made a complex wound simple. Surgical manuals taught

that an amputation should be performed within the first two days following

injury. The death rate from these so-called primary amputations was lower

than the rate for amputations performed after the wound became infected.

Union surgeons performed nearly 30,000 amputations.

Patients

undergoing amputation were first anesthetized. A tourniquet was applied

above the site of the proposed amputation. The skin and muscle were then

cut with amputation knives several inches above the fracture site. The

muscles were pulled up to expose the bone. An amputation saw was used to

cut through the bone. Once the cut was completed, large arteries were pulled

out from the stump tissue with a tenaculum and tied off to prevent bleeding.

The skin muscle was then released and the tissue sutured. Two types of

amputation were commonly used. A circular amputation involved cutting straight

through the skin to the bone and resulted in a stump that was circular

in appearance. A flap amputation required the tissue to be cut leaving

two flaps of skin that were used to create a stump. Fingers and other small