Walking as Art

Footwear

Shoes hold the key to human identity.

Sonja Bata, founder of the Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto (Trueheart

1995:C10)

Terry Gilliam (Monty Python)

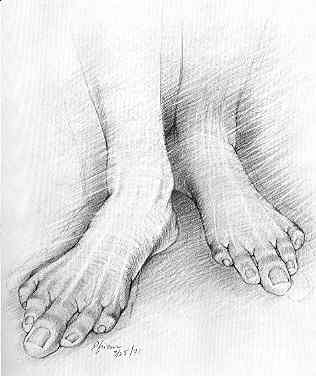

The Foot

The Foot

Humans were wearing shoes at least 40,000 years ago, according to scientists

who have examined the curled-up toes of an ancient skeleton.

Erik Trinkaus

and Hong Shang of Washington University in Missouri, measured the shape

and density of the toe bones from a 40,000-year-old skeleton found in Tianyuan

cave near Beijing.

They then compared them with those from 20th century urban Americans'

feet, late-prehistoric Native Americans and late-prehistoric Inuits.

The pair could make assumptions about footwear because shoes change

the shape of the foot.

A rigid sole meant toes curled far less than when barefoot and less

force was passed through the bones.

That created obvious differences in the three populations, according

to an article

in the New Scientist.

"Modern shoe-wearing Americans have wimpy little toes. Barefoot native

Americans have strong, large toes. Shoe-wearing Inuits lie somewhere in

between," Mr Trinkaus said.

The scientists said the Tianyuan toe bones were most similar to the

Inuits', indicating their owner regularly wore shoes.

Trinkaus,

E. (2005) Anatomical evidence for the antiquity of human footwear use.

Journal of Archaeological Science 32, 1515-1526

In

1938 archaeologist Luther Cressman (from the University of Oregon) excavated

at Fort Rock Cave, located in a small volcanic

In

1938 archaeologist Luther Cressman (from the University of Oregon) excavated

at Fort Rock Cave, located in a small volcanic

butte approximately half a mile west of the Fort Rock volcanic crater

in central Oregon. The Fort Rock Basin is the most northwesterly sub-basin

of the Great Basin, Western North America's vast intermontane desert.

Cressman found dozens of sandals below a layer of volcanic ash, subsequently

determined to come from the eruption of the Mt.

Mazama volcano 7500 years ago. Named for the site where they were first

found, Fort Rock-style sandals have since been

reported from ancient deposits in several Northern Great Basin caves.

Fort

Rock sandals are stylistically distinct. They are twined (pairs of weft

fibers twisted around warps), and have a flat, close-twined sole, usually

with five rope warps. Twining proceeded from the heel to the toe, where

the warps were subdivided into finer warps and turned back toward the heel.

These fine warps were then open-twined (with spaces between the weft rows)

to make a toe flap. Cressman surmised that a tie rope attached to one edge

of the sole wrapped around the ankle and fastened to the opposite edge.

Fort

Rock sandals are stylistically distinct. They are twined (pairs of weft

fibers twisted around warps), and have a flat, close-twined sole, usually

with five rope warps. Twining proceeded from the heel to the toe, where

the warps were subdivided into finer warps and turned back toward the heel.

These fine warps were then open-twined (with spaces between the weft rows)

to make a toe flap. Cressman surmised that a tie rope attached to one edge

of the sole wrapped around the ankle and fastened to the opposite edge.

Most dated Fort Rock-style sandals are from Fort Rock Cave, but directly

dated sandals of this type are also known from Cougar Mountain and Catlow

Caves. Directly dated Fort Rock style sandals range in age from at least

10,500 BP to 9200 BP (based on dendrocalibrated radiocarbon ages). For

more information, refer to Connolly and Cannon 1999.

Directly dated Fort Rock-style

sandals, northern Great Basin.

|

14C

Age

|

Lab No.

|

Age Range (cal

BP, 1 sigma)

|

Dated

Material

|

Site

|

Reference(s)

|

|

9188±480*

|

C-428a

|

10,920-9650 BP

|

sagebrush

bark

|

Fort

Rock Cave

|

Arnold

and Libby 1951

|

|

8916±540*

|

C-428b

|

10,440-9380 BP

|

sagebrush

bark

|

Fort

Rock Cave

|

Cressman

1951; Bedwell and Cressman 1971

|

|

8308±43

|

AA-30056

|

9380-9240 BP

|

sagebrush

bark

|

Catlow

Cave

|

Connolly

and Cannon 1999

|

|

8510±250

|

UCLA-112

|

9840-9240 BP

|

tule

|

Cougar

Mtn. Cave

|

Ferguson

and Libby 1962; Connolly 1994

|

|

8500±140

|

I-1917

|

9530-9380 BP

|

sagebrush

bark

|

Fort

Rock Cave

|

Bedwell

and Cressman 1971

|

|

9215±140

|

AA-9249

|

10,360-10,020 BP

|

sagebrush

bark

|

Fort

Rock Cave?

|

Connolly

and Cannon 1999

|

|

8715±105

|

AA-9250

|

9870-9520 BP

|

sagebrush

bark

|

Fort

Rock Cave?

|

Connolly

and Cannon 1999

|

The commonly cited 9053±350 age for the "Fort Rock

sandal" is actually an average of these two dates, run on "several pairs

of woven rope sandals" (Arnold and Libby 1951:117). The weighted average

of these two ages produces an age range of 10,390-9650 cal BP.

Arnold,

J. R. and W. F. Libby 1951 Radiocarbon Dates. Science 113(2927):111-120.

Bedwell,

Stephen F. and Luther S. Cressman 1971 Fort Rock Report: Prehistory and

Environment of the Pluvial Fort Rock Lake Area of South-Central Oregon.

In Great Basin Anthropological Conference 1970: Selected Papers,

edited by C. Melvin Aikens, pp. 1-25. University of Oregon Anthropological

Papers 1. Eugene

Connolly,

Thomas J. and William J. Cannon 1999 Comments on "America's Oldest Basketry."

Radiocarbon

41(3):309-313.

Cressman,

Luther S. 1951 Western Prehistory in the Light of Carbon 14 Dating.

Southwestern

Journal of Anthropology 7(3):289-313.

Cressman,

Luther S. 1942 Archaeological Researches in the Northern Great Basin.

Carnegie Institution of Washingon Publication 538. Washington, D. C.

Ferguson,

G. J. and W. F. Libby 1962 UCLA Radiocarbon Dates. Radiocarbon 4:109-114.

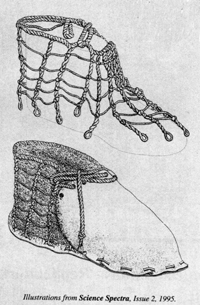

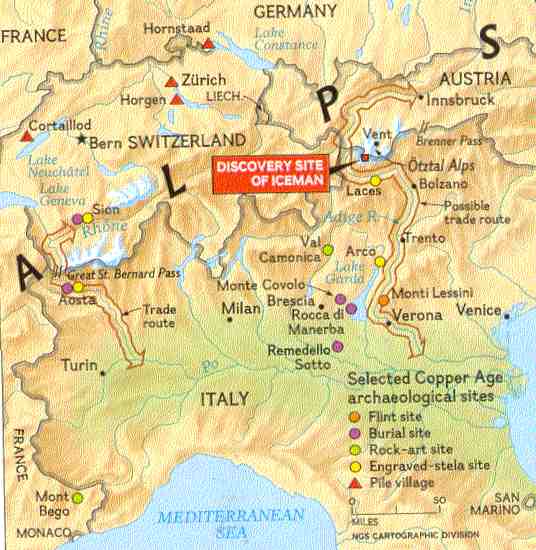

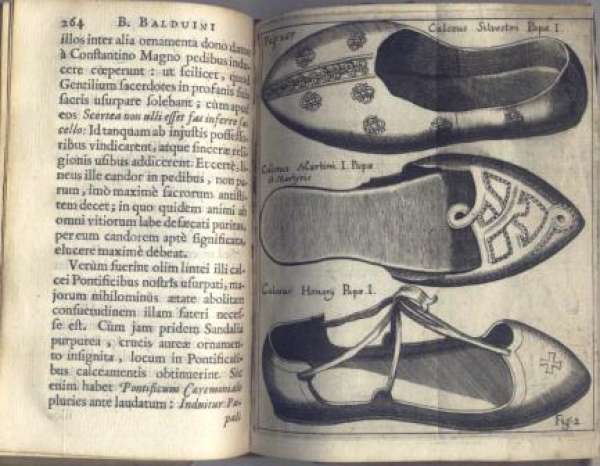

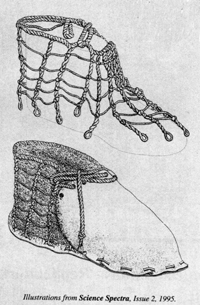

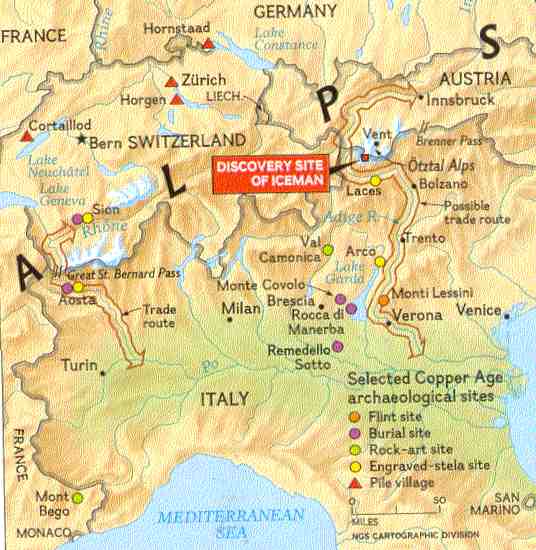

Ötzi, Iceman of the Alps (3350-3300 BC)

On

September 19th, 1991, Helmut and Erika Simon, a couple from Nuremberg mountaineering

in the Ötztal Alps at a height of 3200 m discovered a

On

September 19th, 1991, Helmut and Erika Simon, a couple from Nuremberg mountaineering

in the Ötztal Alps at a height of 3200 m discovered a  corpse,

the upper part of which protruded from the glacier. The well-preserved

body of a 30-to-45-year old man affectionately dubbed "Oetzi" for his resting-place

in the Oetz Valley, near the border with Austria in the Italian Alps, was

in a state of near perfect preservation. Oetzi was eventually dated to

3350-3300 BC (late Neolithic). The man of the ice wore shoes on his feet.

They consisted of an oval leather sole with turned-up edges held

in place with a leather thong. The soles are made of cowhide attached to

straps of a net like construction of knotted grass cords. A net woven out

of grass was attached to this on the inside to hold in place the hay that

was stuffed inside (like socks) as protection against the cold. The shoe

was closed with deer leather uppers attached to the sole by a plain-stitched

leather thong. The linden bark netting covered the tab on the leggin thus

holding the two together. Attached to the sole are upper pieces of leather,

presumably of fur, which formed the boot shape, tied at the ankle with

grass cords.Whereas the sole of the shoe is made of brown bear skin, the

uppers are made of deerskin. The uppers were closed using "shoe-laces".

He is now in the South Tyrol Museum in Bolzano in a special cold storage

chamber (kept at constant 0 to -6 C) .

corpse,

the upper part of which protruded from the glacier. The well-preserved

body of a 30-to-45-year old man affectionately dubbed "Oetzi" for his resting-place

in the Oetz Valley, near the border with Austria in the Italian Alps, was

in a state of near perfect preservation. Oetzi was eventually dated to

3350-3300 BC (late Neolithic). The man of the ice wore shoes on his feet.

They consisted of an oval leather sole with turned-up edges held

in place with a leather thong. The soles are made of cowhide attached to

straps of a net like construction of knotted grass cords. A net woven out

of grass was attached to this on the inside to hold in place the hay that

was stuffed inside (like socks) as protection against the cold. The shoe

was closed with deer leather uppers attached to the sole by a plain-stitched

leather thong. The linden bark netting covered the tab on the leggin thus

holding the two together. Attached to the sole are upper pieces of leather,

presumably of fur, which formed the boot shape, tied at the ankle with

grass cords.Whereas the sole of the shoe is made of brown bear skin, the

uppers are made of deerskin. The uppers were closed using "shoe-laces".

He is now in the South Tyrol Museum in Bolzano in a special cold storage

chamber (kept at constant 0 to -6 C) .

Researchers at Tomas Bata University in the Czech Republic are undertaking

a study of the Iceman's footwear.  They

have constructed three pairs of animal skin shoes that replicate those

worn by Ötzi. Three members of the research team will visit an area

near Ötzi's discovery site, put on the replicas, and take a two-hour

hike. The shoes will be removed and studied. Afterwards, researchers intend

to donate them to an unnamed museum. The task of making replicas of his

shoes was not easy. Besides analyzing the various materials used to construct

the original shoes, researchers had to determine how the Iceman (or his

shoemaker) cut and tanned the skins. They also wondered whether the dried

grass still grew in the region. Analysis revealed that fats from animal

brains and livers were used to make the tanning solution, that a flint

rock was used to cut the skins, and that the same grass still grows. These

details were used in constructing the replicas.

They

have constructed three pairs of animal skin shoes that replicate those

worn by Ötzi. Three members of the research team will visit an area

near Ötzi's discovery site, put on the replicas, and take a two-hour

hike. The shoes will be removed and studied. Afterwards, researchers intend

to donate them to an unnamed museum. The task of making replicas of his

shoes was not easy. Besides analyzing the various materials used to construct

the original shoes, researchers had to determine how the Iceman (or his

shoemaker) cut and tanned the skins. They also wondered whether the dried

grass still grew in the region. Analysis revealed that fats from animal

brains and livers were used to make the tanning solution, that a flint

rock was used to cut the skins, and that the same grass still grows. These

details were used in constructing the replicas.

Sandal, 8000 BC

Sandal, 8000 BC Soft

boots 500 AD

Soft

boots 500 AD

Poulaine 1200

Poulaine 1200 Duck's

Bill 1500

Duck's

Bill 1500

Slippers

1700

Slippers

1700 High-heel 1800

High-heel 1800

1920

1920 1950

1950

1960

1960 1970

1970

Australian Aboriginal sandals

made from Emu feathers

Australian Aboriginal sandals

made from Emu feathers

As usual, the human race has one foot in the grave. And as our political,

military and environmental crises escalate, the second foot may follow.

Or, to borrow another podiatral turn of phrase, the other shoe will fall.

As we teeter on the edge of the abyss, it seems a good time to amuse ourselves

by taking a look

at, yes, feet. As a distraction from our army-booted march to disaster,

let's look at some of the

bizarre facts surrounding footwear.

What follows is an Emma Tom-ish exercise in shoe fetishism. It's a consequence

of my tripping

over a scholarly version of Imelda Marcos. Cameron Kippen, who speaks in

the richest of Scottish

brogues, is a lecturer in podiatry at the Curtin Institute of Technology

in Perth, where he teaches

about brogues of a different sort. Along with boots, slippers, sandals,

galoshes, wellies, high-heels

and clogs.

These days we seem inured to shock. Human proclivities and perversions

no longer raise eyebrows

or frisson. But when Cameron opened Pandora's shoe box and the filthy truth

about feet escaped, I

felt a mixture of fascination and repulsion.

For example, in the high Middle Ages, men began to wear long-toed shoes

called pigaches or

poulaines. Cameron explained that the fashion lasted more than 300 years,

during which the

extensions became longer and longer until walking was all but impossible.

Blatantly phallic, the

style required the toes of the shoe to be connected to the knee with a

chain so as to prevent

tripping.

And young bucks started to stuff wool and moss into the extensions to keep

them erect. To

emphasise the erotic implications of these medieval winklepickers, it was

customary to paint them

flesh pink. And allow them to flap, Cameron notes, with lifelike mobility.

Were talking about the ends of the feet being extended by up to 60cm. Small

bells were often

attached to the end of the poulaine to indicate that the wearer was a willing

partner in sexual frolic.

Playing footsie under the table became increasingly rampant. While boring

conversations were

being held over the meal, the poulaines were being employed under the petticoats

and between the

thighs of female guests. Consequently even a simple three-course dinner

could become

multi-orgasmic.

Polite society was outraged by the poulaines and youths were chastised

for standing on street

corners waggling their toes suggestively as women walked by. Little wonder

that the Catholic

Church saw poulaines as a threat to virtue, chastity and decency. Apart

from anything else, they

physically prevented men from kneeling in prayer.

Branding the shoes as Satan's curse - or Satan's claw - the Vatican passed

laws against them.

Nonetheless they maintained their popularity, even when the clergy insisted

that the Black Death

was God's revenge for, yes, a style of shoe. (Incidentally, few women wore

them because, at the

time, members of their gender were being persecuted as witches if they

wore unusual clobber. And

a pair of poulaines was enough to have you burned at the stake.)

According to Cameron, what shooed these shoes was the death of Duke Leopold

II of Austria, who

died when his poulaines impeded him from escaping assassins. Another factor

was French king

Charles VIII's polydactylism - he had six toes on each foot. To accommodate

them comfortably

required broad, square-toed shoes that helped change the fashion.

As erotic as the poulaine, the duck's bill shoe was broad enough to accommodate

even Charles

VIII's feet. They were as much as 30cm wide, forcing wearers to adopt a

waddling gait. The uppers

were made from silks, brocades and velvet and the shoes were heavily padded,

puffed and

embroidered.

The upper of the shoe had fine cuts in the leather, says Cameron, to show

the coloured hose or

sumptuous lining beneath. Often the shoes were lined with soft fur to resemble

pubic hair and as the

foot moved, skin could be observed through the opening and closing slits,

vagina-like.

And to think that, as a bodgie in the 1950s, I thought I was being outrageous

when I had a duck's

bum haircut and a pair of blue suede shoes.

For centuries, shoes tended to be largely rationed to the high and the

mighty, to pharaohs, kings

and courtiers. Even when they became more common in the Christian era,

they remained expensive

and exclusive. Costs were so prohibitive, people bequeathed their footwear

to family and loved ones,

says Cameron. Hence the saying, following in your father's footsteps.

Ancient Greek women of ill repute often wore elevated sandals to attract

men's attention. According

to Cameron, this led to a sexy wiggle that created an audible clacking

when walking. Which, in due

course, must have produced an almost Pavlovian response in members of my

weak and suggestible

sex.

But the modern high heel evolving into the stiletto seems to derive from

Catherine de' Medici in

16th-century Florence. Diminutive in stature, she wore high heels to her

wedding - the style

becoming an instant success.

Down the track, Louis XIV of France became fanatical about them and forbade

any other than the

privileged classes from wearing high heels, on penalty of death. But then,

the Sun King was also

short and needed all the help he could get.

Cameron explains that the connection between sexuality and the foot originates

in our species' bold

decision to walk upright. Apparently our bipedal stance has influenced

the anatomical development

of what Cameron calls the wobbly bits - buttocks, bosoms, tummies and hips.

And where

quadrupeds largely hide their sexual bits and pieces, we uprights are,

one and all, flashers.

Moreover, we're the only species able to copulate standing up and facing

each other. Which recalls

a joke ``Diamond Jim'' McLelland once told me. Why do Methodists disapprove

of having f---s in

darkened doorways? Because it might lead to dancing.

Wilder Penfield, a 20th-century neurosurgeon, identified the parts of the

brain responsible for

orgasmic activity - and found they lay in close juxtaposition to the section

responsible for feet.

Thereby confirming Freud's belief, says Cameron, of a strong link between

feet and sexuality.

But enough of this. I feel a strong compulsion to rush off and buff my

shoes. Those of you wanting to

put your toes into other people's business can read Cameron's e-book on

the history of footwear at:

www.podiatry.curtin.edu.au/history.html. For my own part, after burnishing

my shoes to

maximum brightness, I shall take a cold shower.

Andy

Warhol (who suffered from St. Vitus Dance)

Andy

Warhol was born Andrew Warhola in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, as the son

of immigrants from Ruthenia, where the current boundaries of Poland, Slovakia,

Hungary, Romania and the Ukraine meet. His father, Andrej, who travelled

much on business trips, died when Warhol was 13. When he was eight (1936),

according to his mother Julia, he caught rheumatic fever which developed

into chorea (or St

Vitus Dance). In the quixotic Philosophy, he calls it a nervous

breakdown. One should remember, when trying to take his books at face value,

that he didn't entirely write them, and that he was a liar.) Biographer

Bockris reports that Andy came down with chorea in the autumn of 1938,

and that illness kept him away from school, an invalid at his mother's

side; he occupied a bed off the kitchen for a month. Symptoms of chorea

included skin blotches and uncontrolled shaking. Both echoed in Warhol's

future, and though he left no direct verbal commentary about what it felt

like to shake or to endure dermatological disfigurement, in his mature

artworks he refracted these experiences, letting stigma reverberate in

painting, film, and performance. Tese later artistic recastings of St.

Vitus' Dance represent childhood trauma's consummation, cancellation, and

vindication. He found it difficult to control his hand to write or draw

and was forced to stay in bed for a month. During this time, his mother

provided him with a steady supply of coloring and comic books, magazines,

and paper dolls, which enabled him to continue his art-making despite his

condition. While incapacitated he played with a Charlie McCarthy doll and

made paper cutouts, cultivating early the propensity for fantasy which

characterized his personality, Besides altering his birth date and name,

Warhol underwent plastic surgery in the 50's to trim his bulbous, red nose

but was angered when the operation failed to lend him the glamour he so

desperately desired. Also at this time he began dreaming of being a Hollywood

star and even wrote to some of his favorite celebrities. He was an albino,

with blotchy skin, and was taunted as Spot by his schoolmates. He had linguistic

problems stemming from his home environment. At college his fellow students

thought he had "a childlike duality about him". He was still living with

his mother until the early '70s.

Andy

Warhol was born Andrew Warhola in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, as the son

of immigrants from Ruthenia, where the current boundaries of Poland, Slovakia,

Hungary, Romania and the Ukraine meet. His father, Andrej, who travelled

much on business trips, died when Warhol was 13. When he was eight (1936),

according to his mother Julia, he caught rheumatic fever which developed

into chorea (or St

Vitus Dance). In the quixotic Philosophy, he calls it a nervous

breakdown. One should remember, when trying to take his books at face value,

that he didn't entirely write them, and that he was a liar.) Biographer

Bockris reports that Andy came down with chorea in the autumn of 1938,

and that illness kept him away from school, an invalid at his mother's

side; he occupied a bed off the kitchen for a month. Symptoms of chorea

included skin blotches and uncontrolled shaking. Both echoed in Warhol's

future, and though he left no direct verbal commentary about what it felt

like to shake or to endure dermatological disfigurement, in his mature

artworks he refracted these experiences, letting stigma reverberate in

painting, film, and performance. Tese later artistic recastings of St.

Vitus' Dance represent childhood trauma's consummation, cancellation, and

vindication. He found it difficult to control his hand to write or draw

and was forced to stay in bed for a month. During this time, his mother

provided him with a steady supply of coloring and comic books, magazines,

and paper dolls, which enabled him to continue his art-making despite his

condition. While incapacitated he played with a Charlie McCarthy doll and

made paper cutouts, cultivating early the propensity for fantasy which

characterized his personality, Besides altering his birth date and name,

Warhol underwent plastic surgery in the 50's to trim his bulbous, red nose

but was angered when the operation failed to lend him the glamour he so

desperately desired. Also at this time he began dreaming of being a Hollywood

star and even wrote to some of his favorite celebrities. He was an albino,

with blotchy skin, and was taunted as Spot by his schoolmates. He had linguistic

problems stemming from his home environment. At college his fellow students

thought he had "a childlike duality about him". He was still living with

his mother until the early '70s.

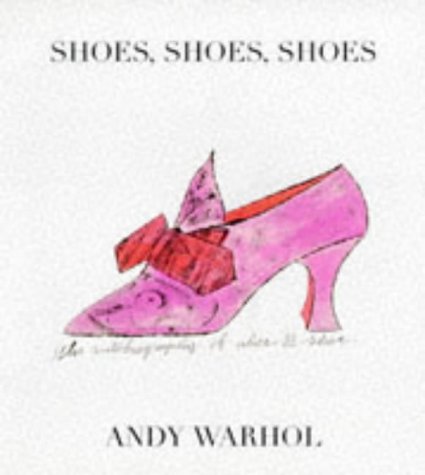

Shoes, shoes, shoes (book cover)

Shoes, shoes, shoes (book cover)

His original aspiration was to be a tap dancer, like his first idol,

Shirley Temple. Coming down with chorea, he became a sort of

dancer. The uncontrolled shaking, at first undiagnosed, leading

others to think him clumsy and febrile, took the Shirley fantasy

somewhere dark: tap is conscious, while St. Vitus' Dance is

hapless. The debate that will later rage over whether Warhol

made his own art, or whether he just had assistants do it, begins

with the chorea question: who controls Andy's physical

movements? His entire career, he will want to pretend not to be

their author. From the age of eight he understood possession: and

therefore he would revise the myth of artistic inspiration, whether

demonic or aetherial, and reconceive his body as a machine

transmitting movements that bypass consciousness and willpower,

that automatically repeat, and that embarrass. When he was a

college student at Carnegie Tech, studying art and design, he

joined the Modern Dance Club, consisting entirely of young

women, himself excepted. Arriving in New York, he would live

with dancers. His films feature dancers, such as the

aforementioned 1965 portrait of Paul Swan—more Gloria

Swanson than Rudolf Nureyev. Another dancer who would

illustrate, for Warhol, the confusion between deliberate gesture

and unwilled spasm was Freddy Herko, who appeared in several

early films, and who literally danced himself to death (suggesting a

vestige of Totentanz in St. Vitus' Dance): Freddy put Mozart's

Coronation Mass on the hi-fi and leaped out the window.

Andy's St. Vitus' Dance (and the sickbed time spent with his

mother) may not have sent him melodramatically into death's

arms, but it altered his sense of touch—heightening it, turning it

into a difficulty not lightly to be engaged. Thereafter he preferred

not to be touched; hyperaesthetic, Andy as an adult would visibly

recoil when a person attempted a handshake, a hug.

After St. Vitus' Dance, with its erratic movements, Andy next

would confront stillness. His father died when Andy was thirteen.

According to Julia, her husband drank poisoned water: "Andy

was young boy when my husband die. In 1942. My husband

three years sick. He go to West Virginia to work, he go to mine

and drink water. The water was poison. He was sick for three

years. He got stomach poisoning. Doctors, doctors, no help."

Andy would remain fascinated by motionlessness—resting

bodies, arrested by photography; his movies (which he and

assistant Gerard Malanga called "stillies") preferred static objects

and near-motionless individuals. The film moved, but the subjects

didn't. Nor do boxes or paintings move. The only thing moving, in

much of Warhol's art, is time, lapping over icons.

Andy was terrified of his father's dead body: downstairs, laid out

for three days, as was customary (the family was Byzantine

Catholic). Andy refused to pay his respects. He hid under his

bed. Death, he now understood, was permanent stillness; until

then, it might not have occurred to him that motion, a St. Vitus'

affliction he'd wanted to stop, would eventually halt forever.

Andrej's dead body, with Julia sitting beside it, proved motion to

be not such a bad thing.

HC Westermann

The

Last Ray of Hope, 1968-a pair of Westermann's Marine-issue boots, polished

and waxed again and again to a perfect, obsidian-like blackness, in homage

to Maxim Gorky's remark that a strong pair of boots "will be of greater

service for the ultimate triumph of socialism than black eyes".

Andy Warhol Pump

Andy Warhol Pump

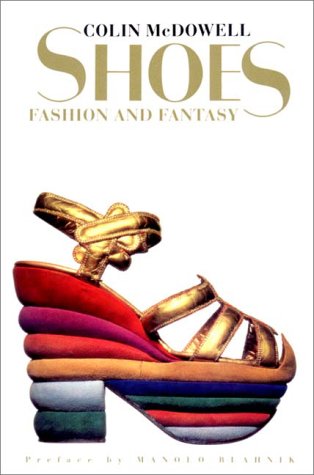

mosaics

mosaics

(book

cover)

(book

cover)

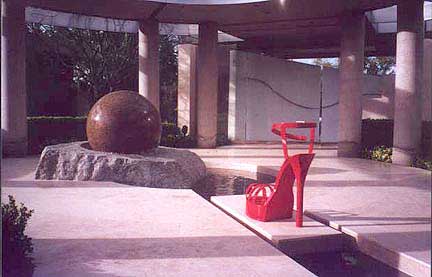

"High Heel Shoes

#1 & #2" (32x31x14) & (32x28x13), welded aluminum

"High Heel Shoes

#1 & #2" (32x31x14) & (32x28x13), welded aluminum

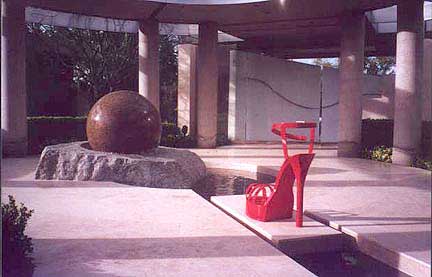

"High Heel Shoe

#4" (39x27x16), steel & enamel

"High Heel Shoe

#4" (39x27x16), steel & enamel

Shoe #4 at home

in Indian Wells, California

Shoe #4 at home

in Indian Wells, California

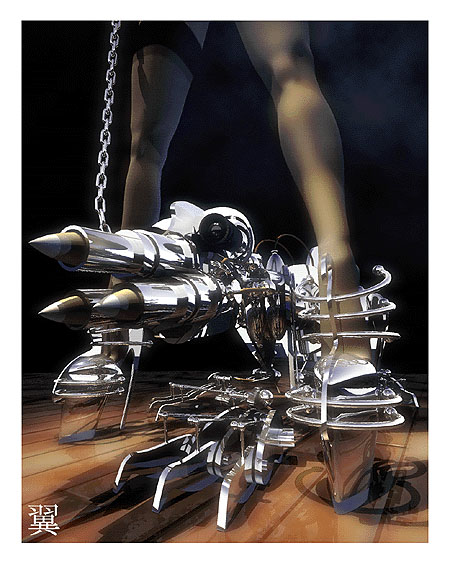

"wearable" high

heel shoes in stainless steel

"wearable" high

heel shoes in stainless steel

3 Foot Shoe private

collection, 36x29x12"

3 Foot Shoe private

collection, 36x29x12"

Spikey 26x17x10.5"

metal work

Spikey 26x17x10.5"

metal work

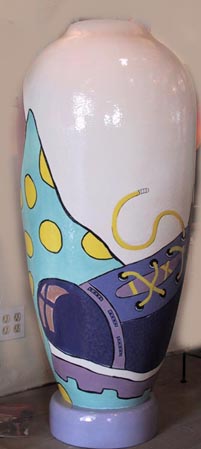

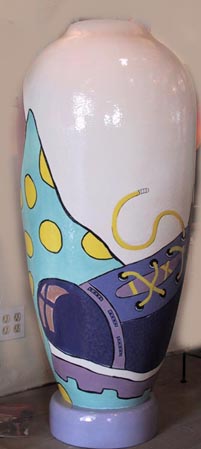

Stepping

into the Millennium, 48" vase

Stepping

into the Millennium, 48" vase  Boot safe

Boot safe

Lacy, metal wall

sculpture

Lacy, metal wall

sculpture  Shoe Stand

Shoe Stand

Ladies of Egypt , Ceramic and metal, 16x20x10"

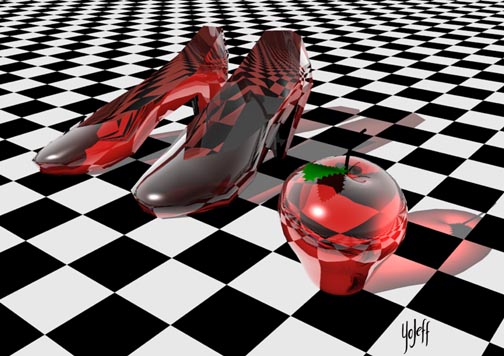

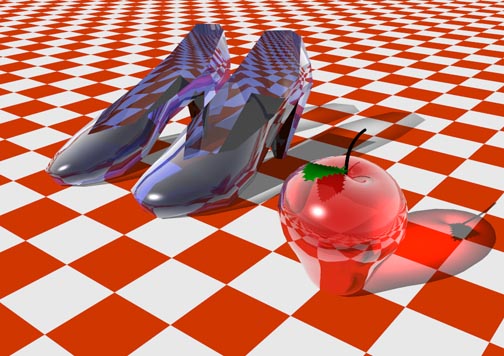

American Shoes,

giclee on canvas

American Shoes,

giclee on canvas

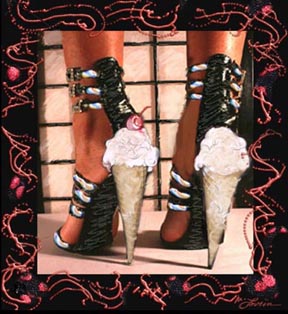

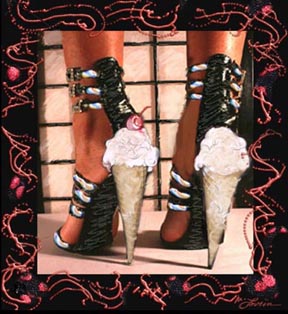

"Ice Cream

Heels", Limited edition print

"Ice Cream

Heels", Limited edition print Proposal, giclee on canvas

Proposal, giclee on canvas

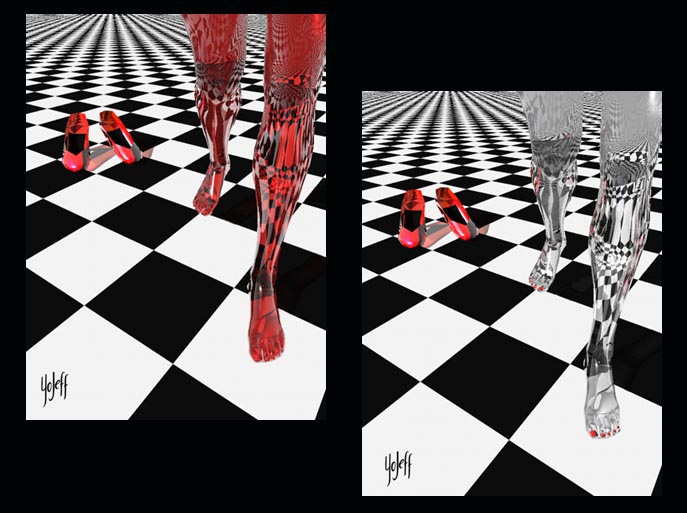

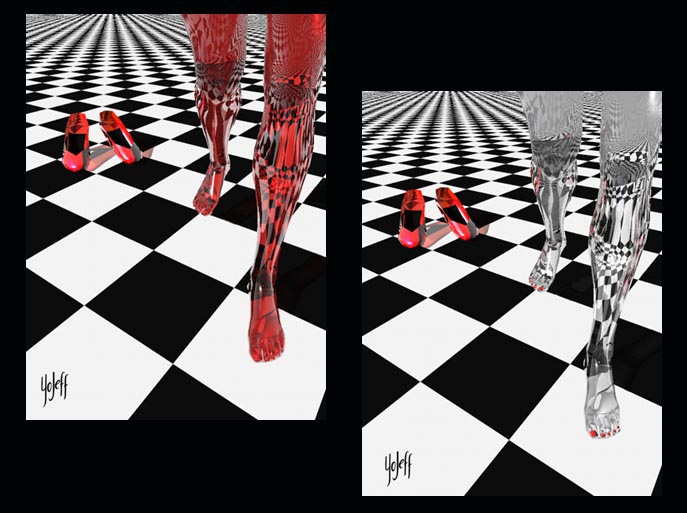

Look Down

in Color, monotype

Look Down

in Color, monotype

Reflection

, giclee

Reflection

, giclee

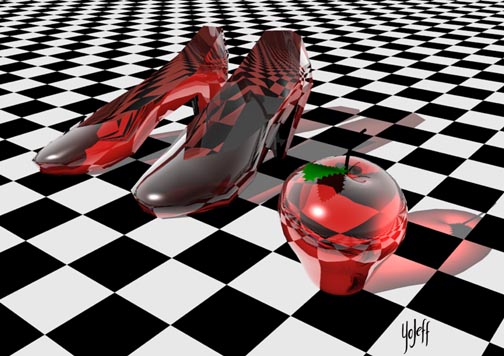

Red glass shoe

Red glass shoe

Blue glass shoe

Blue glass shoe

Annie Ball

Silk covered

tea box

Silk covered

tea box

Patty Van Asperen

Blue

Descending Heels, fused glass bowl

Blue

Descending Heels, fused glass bowl

Glass slipper

Glass slipper

Da Vine, glass

Da Vine, glass

Petroglyph

high heel, rock

Petroglyph

high heel, rock

Darrell Hill

Sunset Boot, 3D

with oil paint

Sunset Boot, 3D

with oil paint

Melba

Boyd

Blue Man

Shoe

Blue Man

Shoe

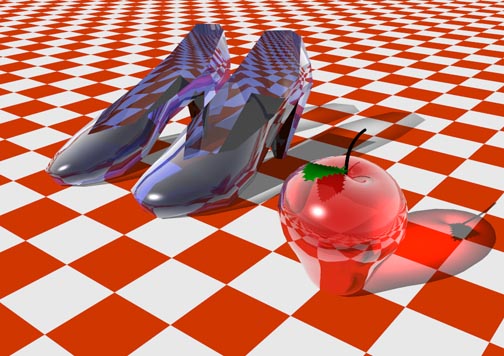

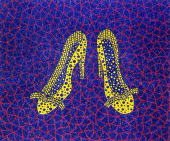

Yayoi Kusama (b. 1929)

Silver Shoes (1976-77)

Silver Shoes (1976-77)

1999

1999

2002

2002

Yayoi Kusama was born 22 March 1929, in Japan. Kusama's paintings, collages,

sculptures, and environmental works all share an obsession with repetition,

pattern, and accumulation. Hoptman writes that "Kusama's interest in pattern

began with hallucinations she experienced as a young girl--visions of nets,

dots, and flowers that covered everything she saw. Gripped by the idea

of 'obliterating the world,' she began covering larger and larger areas

of canvas with patterns." Her organically abstract paintings of one or

two colors (the Infinity Netsseries), which she began upon arriving in

New York, garnered comparisons to the work of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko,

and Barnett Newman. Starting in 1967 she became involved in performance-based

work, and by the late '60s the happenings in which she participated were

receiving much more attention in the popular press than in the art magazines

that had previously reviewed her work. In the early '70s Kusama traveled

between Japan and the United States several times, and she eventually remained

in Japan. During the mid '70s Kusama was hospitalized for psychological

problems, and in 1977 she took up long-term residence at the Seiwa Hospital

in Tokyo, where she set up a studio and has continued her work as an artist.

Diane McLean

Shoe

(Roman sandal), University of Stirling, Scotland

Shoe

(Roman sandal), University of Stirling, Scotland

Lobbs of London

Lobb's of London: Jubilee Shoe, 2002

Lobb's of London: Jubilee Shoe, 2002

Boots made for

an Indian Princess in Arkansas and presented to Mr. Eric Lobb in 1948.

Boots made for

an Indian Princess in Arkansas and presented to Mr. Eric Lobb in 1948.

Roman Shoes

Adult woman's shoes found at archaelogical excavation at Southfleet

(Springhead), Kent in 1801. Originally purple with a pale lining visible

through the openwork and gilded metal thread embellishing the pattern (British

Museum, 2nd-3rd Century AD)

Roman child's leather hobnailed sandal (caliga) with decorative

openwork upper (Bank of England/British Museum)

Light leather Roman shoe known as a carbatina (British Museum)

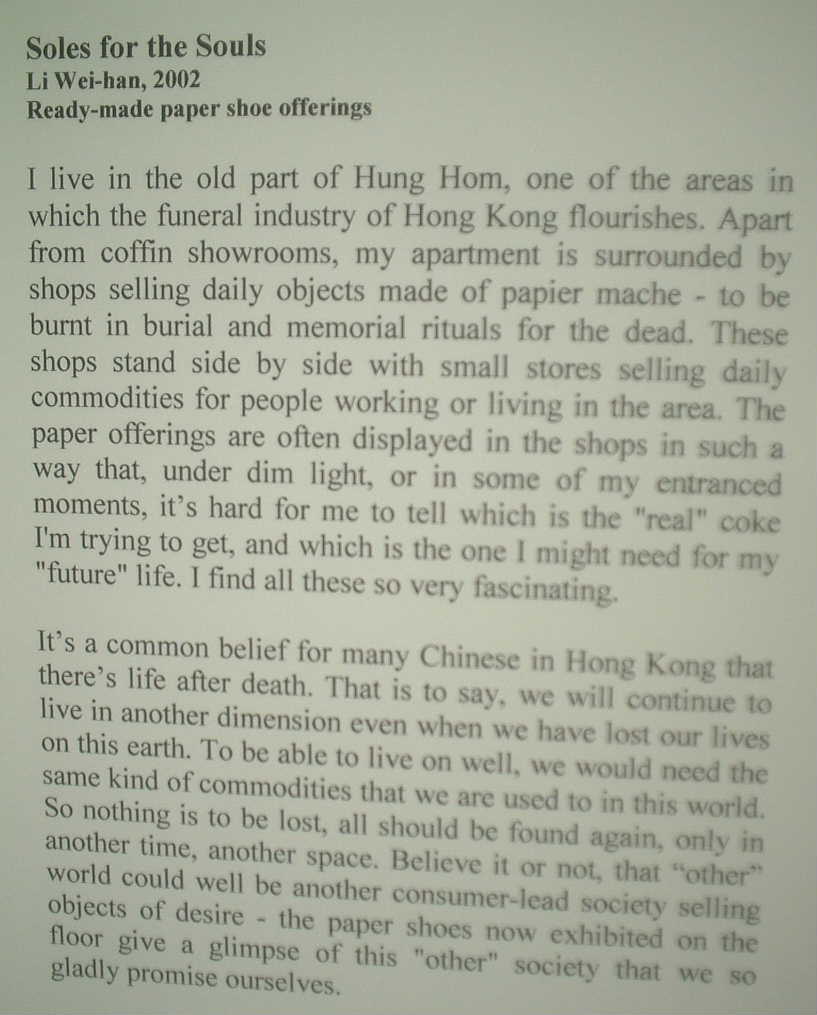

Chinese Paper Shoes

High-heeled three-wheeler

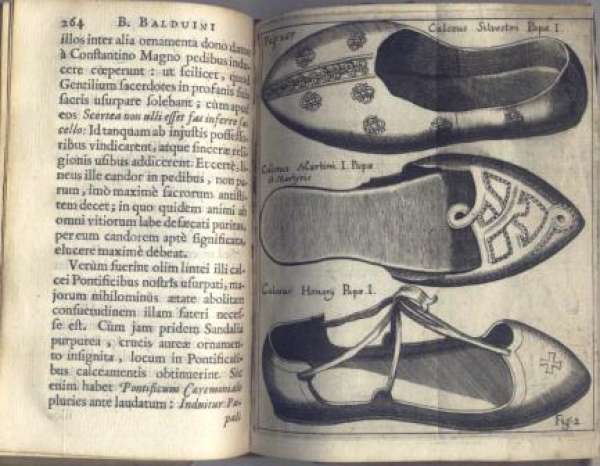

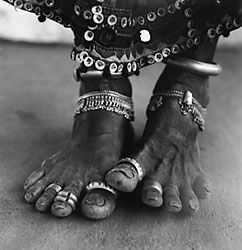

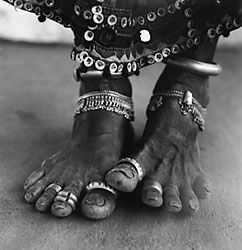

Holy Feet

Holy Feet

Veldhoen took the photographs of the feet while travelling in India

in 1996. Feet are sacred in India and they also carry great importance

for her: Feet take you everywhere in life, they are the number one means

of transport. As the naked foot is in direct contact with the earth, I

believe it passes on personal strength and aura to the trodden ground.

The world's best-known shoe collector, former Philippine First Lady

Imelda Marcos, opened a museum in 2001, in which most of the exhibits are

her own footwear.

The Footwear Museum in Barangay San Roque, Marikina

City, Manila (a district known as the shoe capital of the Philippines)

contains hundreds of pairs of shoes, many of them found in the presidential

palace when Imelda and her husband, President Ferdinand Marcos, fled to

Hawaii in 1986.

"This

museum is making a subject of notoriety into an object of beauty," Mrs

Marcos told reporters.

"This

museum is making a subject of notoriety into an object of beauty," Mrs

Marcos told reporters.

The museum management hopes it will help attract tourism to Marikina,

"They went into my closets looking for skeletons, but thank God, all they

found were shoes, beautiful shoes," a smiling Mrs Marcos said, wearing

a pair of locally made silver shoes for the day.

"More than anything, this museum will symbolise the spirit and culture

of the Filipino people.

"Filipinos don't wallow in what is miserable and ugly. They recycle

the bad into things of beauty," she said.

The exhibits include shoes made by such world-famous names as Ferragamo,

Givenchy, Chanel and Christian Dior, all size eight-and-a-half. The museum

also houses traditional shoes from different countries, as well as footwear

of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, former Presidents Ferdinand Marcos

and Fidel Ramos, some senators and athletes.

During her time as first lady, Mrs Marcos was famed for travelling the

world to buy new shoes at a time when millions of Filipinos were living

in extreme poverty. She reportedly owned over 3000 pairs of shoes

when she was forced to flee the presidential estate. President Marcos'

successor, Corazon Aquino, ordered many of Mrs Marcos' shoes to be put

on display as a demonstration of her extravagance.

While Ferdinand Marcos died in exile, neverseeing his country again

after his fall from grace in a popular uprising, his widow has reintegrated

herself into Philippines life. She has twice run for president and analysts

say she may run for mayor of Manila next May.

Some 200,000 people work in the Marikina district making shoes, with

roads carrying names such as Sandal Street and Slipper Street.

I did not have three thousand pair of shoes. I had one thousand and

sixty.

Everybody kept their shoes there. The maids...everybody.

Our opponent (Cory Aquino) does not put on any make up. She does

not have her fingernails manicured. You know gays. They are for beauty.

Filipinos who like beauty, love, and God are for Marcos.

I get my fingers in all our pies. Before you know it, your little

fingers including all your toes are in all the pies.

Shoes in Museums

In 1998 the Museum of London's exhibit, Sole City: London Shoes From the

1st to the 21st Century, featured contemporary

British shoe designers and explored the designers' penchant for offshore

production. Sogetsu Ikebana School's 1999 Sogetsu Hall exhibition, The

Art of The Shoe, paid tribute to the life and works of Salvatore Ferragamo.

The shoes, exhibited amidst green bamboo structures, were designed from

1927 to 1960, the year of his death.

Museums like France's International Shoe Museum (Le Musée International

de la Chaussure) and Offenbach's German Shoe Museum (Deutsches Ledermuseum

/ Schuhmuseum) have helped preserve centuries of shoe design history. Besides

legacy shoes, the German Shoe Museum features contemporary footwear debuted

at the International Shoe Fair, a trade event in Düsseldorf.

In addition to European and non-European shoe exhibits, 20th century

artists like Günther Uecker, Allen Jones, Caroline Bahr, Gisela Cardaun

and Gaza Bowen, who see the shoe as an art form, are also featured. The

International Shoe Museum showcases 8,000 rare and original items from

around the world, as well as exhibits by contemporary designers.

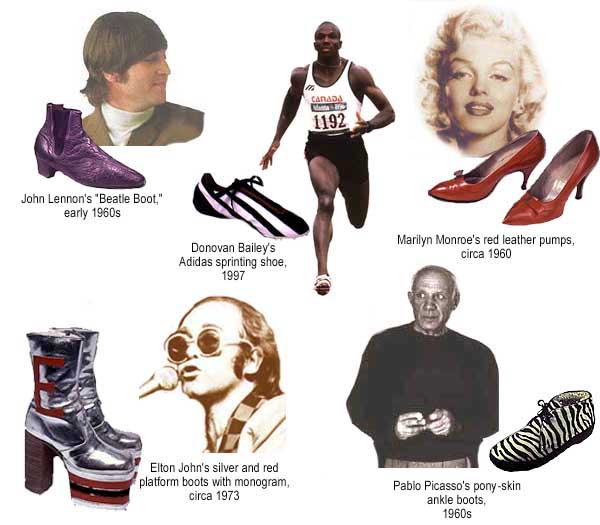

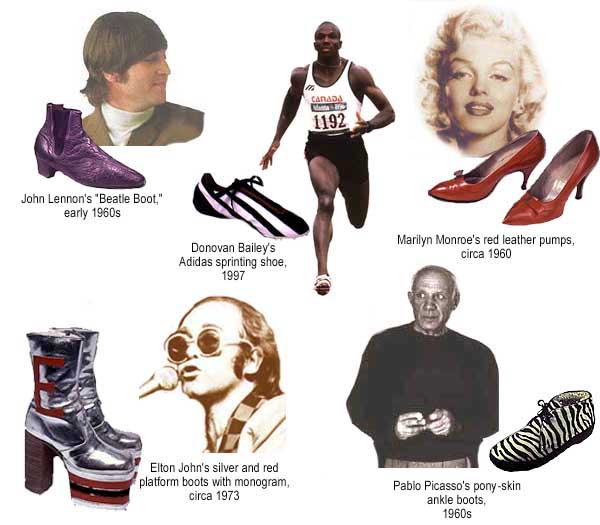

Toronto's

Bata Shoe Museum's exhibits, housed in a angular shoe box design by

architect Raymond Moriyama, include shoes of the ordinary and the renowned.

Virtually step inside Picasso's zebra-striped boots or explore a collection

of ethnological, Western, Indian, circumpolar and other historical artifacts,

from nearly every culture in the world.

Toronto's

Bata Shoe Museum's exhibits, housed in a angular shoe box design by

architect Raymond Moriyama, include shoes of the ordinary and the renowned.

Virtually step inside Picasso's zebra-striped boots or explore a collection

of ethnological, Western, Indian, circumpolar and other historical artifacts,

from nearly every culture in the world.

San Francisco's M.H.de Young Memorial Museum featured footwear in their

1996 exhibit: If The Shoe Fits. In 1998, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts

exhibit, A Grand Design: The Art of the Victoria and Albert Museum, showcased

2,000 years of art from 26 countries, including shoes and boots by Mary

Quant, Vivienne Westwood, Vegetarian and others.

Over 150 athletic shoes were the star attraction in the 2000 San Francisco

Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) exhibition, Design Afoot: Athletic Shoes

1995 - 2000. This exhibit featured designs by Suki Saki, Lulu Longtime

and other artists who have designed shoe for Adidas, Converse, Nike, Oakley,

Polo and Prada while exploring the blurred boundary between function and

fashion.

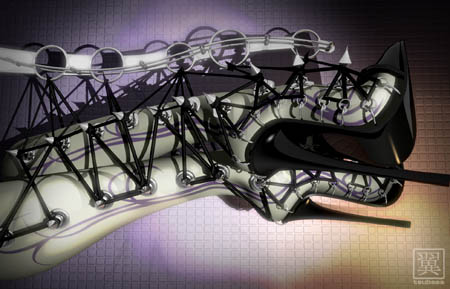

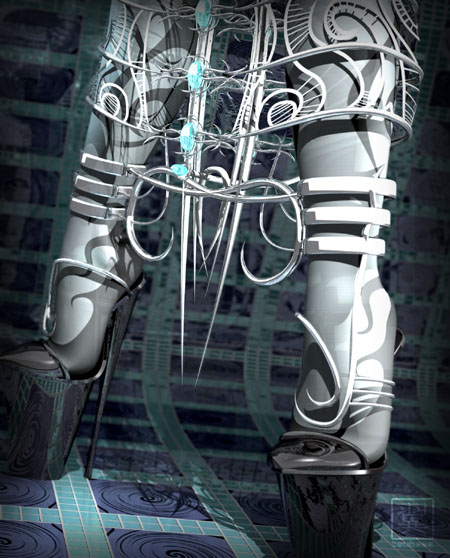

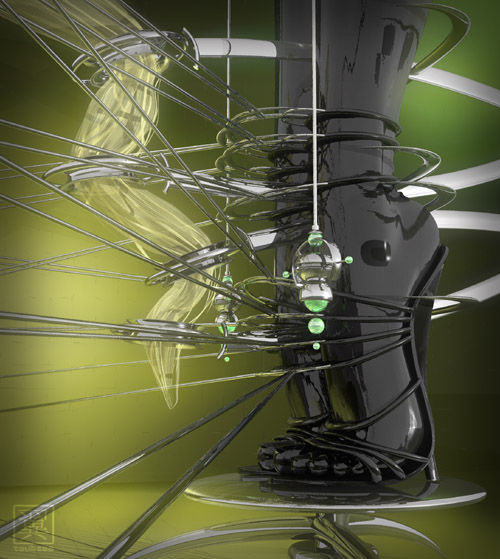

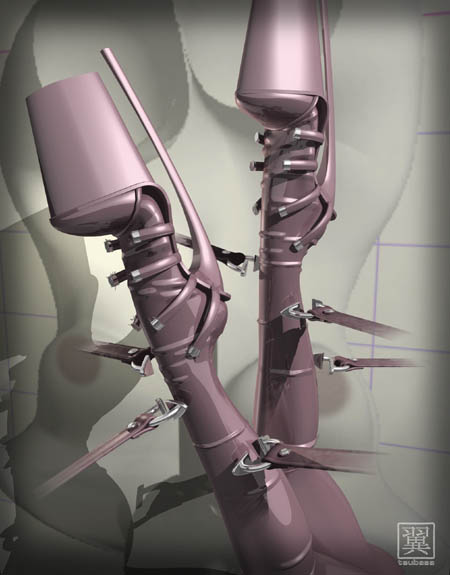

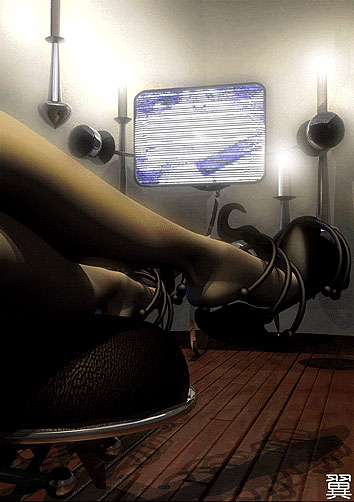

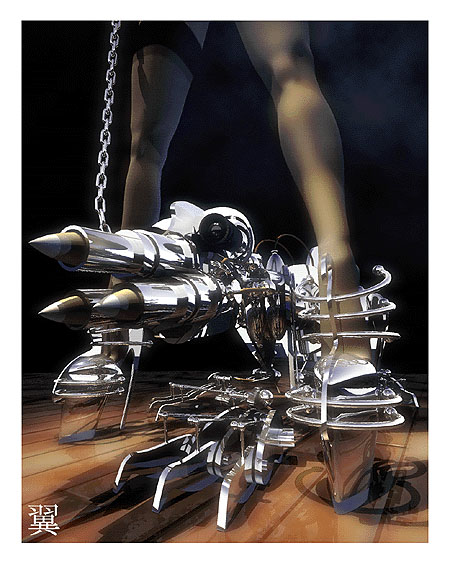

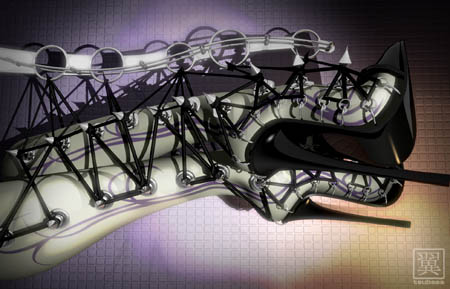

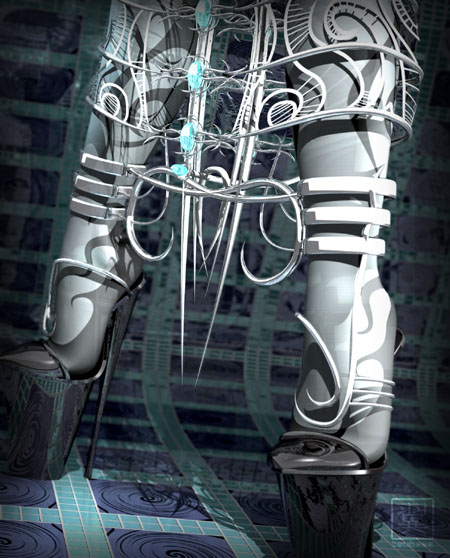

What will future footwear look like?

Will they follow the predictions of Madison Avenue's Committee

for Colour and Trends, who felt that after Helmut Lang's minimalist shoe

designs, like those of Helmut Lang, designers would turn to modernism...

and then what? Will future shoes be takeoffs on the Space Racer and

Relax-O-Shoe? Will shoes be designed by artist/inventors, custom-designed

by man and computer or will they be return to being handmade?

Expressive

Soles: Why Iraqis used shoes to shoo Saddam

I was in a bar (as one frequently is) at the end of a day's labors. There

were televisions lit up, one on

the left, another on the right, with pictures from statue-strewn Baghdad

streets. And just then the

barmaid across from me, clearly thirsting as much for information on another

culture as I was for a

Scotch, asked aloud, and quizzically: "What's with the shoes?!"

How can one not have noticed, and wondered about, the shoes?

In recent days we've seen Baghdadis, Basrans, Kirkukis, Karbalites, Dearbornis--Iraqis

of all

sorts--assaulting every fallen statue of Saddam Hussein, every unseated

portrait of the tyrant, with

their footwear. We've seen leather shoes, plastic sandals, rubber flip-flops,

even (or was this an

illusion?) some Nikes, long-laced and incongruous. Everything but stiletto

heels, which aren't, if I may

be permitted a rare generalization, big in the Arab world, at least not

in public.

These images--these flailings of sole against statuary--have been among

the most charming of any to

emerge from Freed Iraq, and arguably the most intriguing to Western viewers.

One can comprehend

the toppling of the totemic figures in town squares, and one has, in fact,

seen this sort of thing

before: in Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Romania and other places at the end

of the Cold War. But one

never saw men in Vilnius, Cracow, Minsk or Timisoara flay their bronze

or plaster Lenins and

Ceaucescus with their shoes. There may have been some kicking, but no one

in the East Bloc ever

discalced himself to hand-deliver a thrashing to a crippled icon.

So what is it with the shoes in Iraq?

As anyone who has been to the Middle East (or even to countries like India)

knows, the foot and shoe

are imbued with considerable significance.

The foot occupies the lowest rung in the bodily hierarchy and the shoe,

in addition to being something

in which the foot is placed, is in constant contact with dirt, soil and

worse. The sole of the shoe is the

most unclean part of an unclean object. In northern India, where I grew

up, the exhortation "Jooté

maro!" ("Hit him with shoes!") was invoked when one sought to administer

the most demeaning

punishment. (Another footwear tidbit: The effigies of unpopular politicians

in India are regularly

garlanded with shoes and paraded down the streets.)

In the Muslim world, according to Hume Horan, a former U.S. ambassador

to Saudi Arabia, "to have the

sole of the shoe directed toward one is pretty much the equivalent of someone

in our culture giving

you the finger." Matthew Gordon, a historian of Islam, says that since

one takes one's shoes off before

entering a mosque--as a way of maintaining the purity of the place of worship--"the

use of a shoe as

something to hit you with is an inversion, directing impurity and pollution

at the object of the beating."

The fact that the shoe-as-anathema idea stretches across the Arab world

into India suggests that

the cultural aversions (and the attendant insults) predate Islam and may

have had their origins in a

poorly understood--but basically correct--connection between dirt (i.e.,

pollution) and footwear. In

societies where levels of public hygiene are low (e.g., much of the Middle

East and the Indian

Subcontinent), it is still commonplace to remove one's shoes before entering

a private home, and not

just places of worship. Which begs the question, of course, of why shoes

weren't so removed in

medieval Europe, whose streets were just as dung-flecked, or are not so

removed in present-day,

non-Muslim Africa.

But the fact remains that Iraqis today are deriving sumptuous pleasure--part

ritual, part

catharsis--from their chance to hit Saddam with the soles of their shoes.

In this, they are not merely

degrading him but also exacting retribution for bastinadoes suffered in

the past. There probably isn't a

single non-Baath-Party Iraqi who wasn't personally beaten or knocked about

by the authorities--or

who doesn't know someone so ill-used.

Ultimately, there could also be a practical explanation for "the shoes."

It may well be that in

impoverished Iraq, nobody except those in the military could afford decent

footwear. So kick the

bronze head too hard and you hurt your own foot. Better, and safer, to

take the shoe off and go

thwack, thwack, thwack, thwack.

Mr. Varadarajan is editorial features editor of The Wall Street Journal.

Concealed shoes

Steve Harber from Suffolk lives near the village church at Ilketshall St

Lawrence near Halesworth, and wanted to have explained a curious mark on

the tower roof. He wrote: 'The tower has a flat roof with lead covering.

Engraved in the lead are a number of old marks, some of them appear to

be drawn around the engraver's boot. A distinctive common mark within the

foot-shaped marks is a body tied in a sack on gallows. The tower is never

visited and the existence of the marks is not well known. I often wondered

why these are there and who would have put them there.'

The marks on the church tower are engraved into the lead roof. There

are several shoes. Most are dated - from the sixteenth century to the early

twentieth - and they have various engraved marks inside them including

a crown, a swastika and a hanged man. Local archaeologist Mike Hardy pointed

out that the shoes were different shapes - some with pointed toes, some

square and some round.

The shoe marks on the church roof are not hidden shoes. They are drawn

around the outside of a shoe - the shape of the shoe helps with dating

if no date is inscribed. The marks, too, are symbols. The crown meant authority,

and the swastika was a benign symbol until the twentieth century (it gets

its name from the Sanskrit word svastika, meaning well-being and

good fortune). The hanged man also represented a search for spiritual well-being.

There is little in the way of contemporary accounts about this apparently

very common practice, but it was a secretive custom associated with folk

magic.

Sue Constable of Northampton Museum explained that concealing shoes

is a well-known folk custom and is so common throughout the country that

the Museum has set up a Concealed Shoes Index to record all the occurrences.

The custom would appear to be a charm to ward off malevolent spirits who

might enter buildings, particularly homes, at inaccessible places - chimneys

are especially common hiding places. The Museum receives an average of

one find a month, but Sue Constable says that hundreds of finds every year

may well be simply thrown out by builders. In Britain as many as 50 date

from before 1600 and the numbers rise to more than 500 in the nineteenth

century, and then the finds tail off. Shoes are often found hidden in chimneys,

either on a ledge or in specially built cavities behind the hearth into

which items could be placed from above. Sometimes they were hidden under

bedroom floors.

The earliest reference to the use of shoes as some kind of spirit trap

comes from the 14th century. It

regards one of England’s unofficial saints, John Schorn from Buckinghamshire,

who was rector of

North Marston 1290-1314. His claim to fame is that he is reputed

to have performed the remarkable

feat of casting the devil into a boot. The oldest concealed shoes

date back to roughly the same time

as Schorn but there are very few examples from that period - he may have

begun the tradition, or it

may simply be that his legend records a pre-existing practice.

Over 1200 examples recorded so far. Many people who have discovered

shoes in buildings feel very strongly about not removing or even discussing

them. It is important, therefore, to treat individual feelings about

these items sensitively.

26.2% of shoes are found in chimneys, usually on a ledge within the chimney.

Shoes can be discovered in large groups and sometimes with

other artifacts. 11.3% are pairs of shoes - most are odd. 40%

of shoes belonged to children.

The shoe was not a cheap item, it may have been one of the most expensive

purchases a family had

to make. Therefore shoes were repaired as much as possible before

being discarded. Clearly, by the

time the shoe was discarded it provided a unique record of the wearers

individual foot. Here we may

have a similar principal to the witch-bottle, fooling the witch/spirit

that the person is there in the

chimney. It was probably hoped the shoe would trap the spirit or

act as a decoy of some sort. The

location of shoes, often either within or near to the hearth, does suggest

some kind of protective

function.

There are some specific points to record in the case of shoes in addition

to the general advice given

on the 'how you can help page'. The location of the find in relation

to north in the building should be

recorded, along with how many lace holes they have, whether (in your opinion)

it was a man's,

woman's, boy's, girl's, child's shoe and the date of the find also.

As with all finds, it is important to

attempt to ascertain the date of the building.

Garments have also been found concealed in buildings and may have a similar

significance in that

they are 'valuable' rubbish. They too have highly important personal

significance and may be a

similar practice to that of concealed shoes. Some research and conservation

on these finds has been

undertaken at the Textile Conservation Centre in Winchester.

Shoes were thought to have a special quality. They were repaired and

repaired until they became very individual. They came to be thought of

as the item of clothing which most clearly contained the soul of the individual.

There are suggestions that they were a fertility symbol. In the nursery

rhyme, the old woman who lived in a shoe had so many children she didn't

know what to do.

June Swann was the pioneer of research into concealed shoes with an article

in 1969 for the Journal

of Northampton Museum and Art Gallery - this museum holds a very

large collection of concealed shoes.

Further reading

Emily Brooks, 'Watch Your Step' (The National Trust Magazine, no.91,

Autumn 2000)

Timothy Easton, 'Spiritual Middens' in Encyclopedia of Vernacular

Architecture of the World, vol1, (Cambridge University Press, 1997)

Ralph Merrifield, The Archaeology of Ritual and Magic (Batsford,

1988)

Iona Opie and Moira Tatem, editors, A Dictionary of Superstitions

(Oxford Paperbacks, 1992)

David Pickering, Cassell Dictionary of Folklore (Cassel Reference,

1999)

Jacqueline Simpson and Steve Roud, A Dictionary of English Folklore

(OUP, 2001)

June Swann, 'Shoes concealed in buildings' (Journal of the Costume

Society no.30, 1996, pp.56-99)

Cameron, Pitt, Swann and Volken, ‘Hidden Shoes and Concealed Beliefs’,

Archaeological Leather Group Newsletter, issue 7, Feb 1998.

| Petrus

Camper (1722-1789) on the Shoe

Petrus Camper, "On the Best Form of Shoe,"

translated from Dutch into English by James Dowie, The Foot and Its

Covering (London: Hardwicke, 1861): xxvii-44. |

| Jean-Jacques Rousseau's commentary about native's view

of European

shoes, A Discourse Upon The Origin and Foundation of the Inequality

Among Mankind 1761 anonymously-translated English publication preserved

all of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's original footnotes. |

Handout |

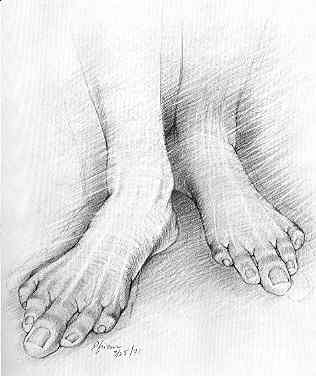

Plate I, Fig. 1. The foot is divided into three parts, of which

the principal, N, E, is called the Tarsus; E, D, the Metatarsus;

and D, A, the Toes. |

Plate I, Fig. 2. The change which takes place in the foot when

we walk is of great importance: the great toe, A, K, then rests

upon the ground; the metatarsus, or instep, rises from b to B;

and the line d, c, lengthens and extends to B, increasing

the interval c, B, which is in this figure 1/4 of an inch French

measure, and, in consequence, a whole inch in nature.

The soles of our shoes and boots, which are generally made of the strongest

leather, become, in consequence of this elongation of the foot, too short

in proportion. The shoe then pinches the heel, and produces still worse

effects upon all the toes, especially the great toe; for as the sole cannot

yield from c to B, A yields towards c, and the great

toe is bent as at f, forming the [blue] angle

e,

f, D, together with the rest of the toes. Thus are produced

corns upon the joints, and other painful deformities of the feet. |

Plate I, Fig. 3. The astragalus, R, M, I, which supports

at R the whole weight of the body, is thus sustained by two [red]

oblique lines, R, B, R, A.

The great toe becomes bent towards P, and the higher the heels,

the greater will be the distortion,—the centre of gravity, R, acting

more and more in the line R, a; and the higher the heel and the

smaller the sole, the greater becomes the risk of falls and sprains. |

Plate II, Fig. 6. As the leg rests on the foot, and the centre

of gravity acts in a line perpendicularly, a line designated by Borelli

linea

propensionis, and represented by R,

S, in Figs. 3 and 6, it follows that this line ought always

to be observed.

The best position for the buckle or fastening of a shoe is, therefore,

directly over the top of the instep, neither too high nor too low, exactly

over the spot where the triangular ligament connects the tendons of the

extensors of the toes with the bones of the tarsus and metatarsus, at O,

N,. |

Plate I, Fig. 4. It is more than probable that in those persons

whose feet have not been distorted by the use of high heels, the heel-bone

receives the anterior part of the astragalus (H) upon the eminence

M,

L, which is then divided into two small sinuses (E and

F,

Fig. 4), separated by a space, K. |

Plate II, Fig. 8. If we consider the

sole of the foot (Fig. 8), we shall see that the diagonal line of this

supposed lozenge does not pass through its centre, but that the exterior

portion, A, B, D, M, Fig. 8, considerably exceeds the interior,

A,

B, E, N.

The sole of the foot is generally of the form represented in Fig. 8;

the part comprising the toes, E, D, B, in F, E, occupying

about one-third of the whole length of the foot.

The toes are naturally all parallel to the diameter A, B, as

I have represented them in Fig. 8, which is the outline of a foot that

has not been distorted by ill-made shoes.

There is an old and most unreasonable custom of making the shoes for

both feet alike, from one and the same last, with the additional absurdity

of giving the sole a certain arbitrary form, as at A, O, D, S, B, R,

E, N, Fig. 8. |

Has anything really changed

since Camper's day....?!

|

| The [red] sole, A, N, E, R, B, S, D, O,

Fig.8, copied from the latest Parisian pattern, was intended for

the [blue] sole of the foot, A, I, Z, K, M, A,

Fig. 8!! |

|

Plate I, Fig. 5. Very frequently, however, we find but one sinus,

as at E, F, Fig. 5.

It appears to me very probable, then, that these sinuses become united

from the pressure to which they are subjected by high heels, causing the

obliteration of the division K. |

Plate II, Fig. 7. |

Plate II, Fig. 9. The erect position being a necessary prelude

to walking progression, it may be well, in idscussing this subject, to

look to what the celebrated Borelli has left us in his excellent work on

the Animal Motions. Our principal business being to explain the manner

in which we raise our fett from the ground in walking, we may turn to Fig.

9, where A, C, B represents the length of the leg and foot, turning

upon the hipjoint at A. C indicates the knee. Let us imagine

that a man standing on his right foot begins to walk along the street,

G,

F, it is certain that if there should be a stone, E, B, at B,

he will strike his foot against it; but if the heel of the shoe should

be of the height E, B, the centre of movement at the hip being thus

raised to D, he will avoid it, because the foot will pass from H

to I. |

|

| www.shoeme.com/history.htm

www.shoesonthenet.com/terms.html

Beauty is

Shape by Pauline Weston Thomas for Fashion-Era.com

The

Cultural Body Alterations University of Iowa Medical Museum

www.bata.com/just_fun/foot_shoecare/anatomy.htm

www.savingfeet.com/Home/FootProblems/Foot_Anatomy.html

www.nefca.ca/find-ft-nurse/ftanatomy.asp |

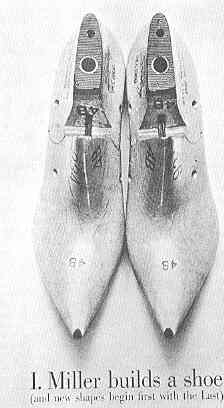

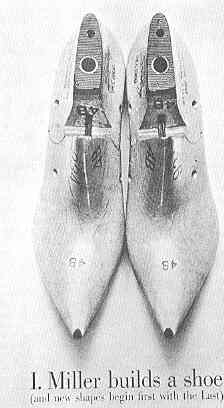

Advertisement, 1961. (I. Miller Shoes)

Bernard Rudofsky, The Unfashionable Human Body (Garden City,

New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1971): 116. |

|

"The foot that fits the shoe: According to the gospel of our shoemakers,

the big toe ought to be in the place of the third one. Hence shoes for

symmetrical feet are not just a fashion but an unwritten law. To drive

home the immensity of this abomination, Bernard Pfriem, portraitist of

the human body par excellence, has obliged the author by interpreting the

shoe designers' unfulfilled dream." 3/28/71

Bernard Rudofsky, The Unfashionable Human Body (Garden City,

New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1971): 113. |

[

G.

de Buffon (1707-1788) ] [ Petrus

Camper (1722-1789) ] [ L.-J.-M.

Daubenton (1716-1800) ] [ Enlightenment

Anthropology ] [ Orang-Utang

Graphics ] [ 18th-Century

Concepts ] [ 17th-Century

New France ] [ Translations

] [ N.

B. Jenison (1876-1960) ] [ Dr.

Meijer's Résumé ] [ Conference

Papers ] [ Publications

]

[ Dr.

Meijer's Book ] [ Rodopi

] [ Amazon.com

] [ PDF

Order Form ]

[ 1st

Review ] [ 2nd

Review ] [ 3rd

Review ] [ 4th

Review ]

[ Index

] [ Sitemap

]

Miriam Claude Meijer, Ph.D. |

Adult Mens and Womens Shoe Size Conversion Table

| Europe |

35 |

35½ |

36 |

37 |

37½ |

38 |

38½ |

39 |

40 |

41 |

42 |

43 |

44 |

45 |

46½ |

48½ |

Europe |

| Japan Men |

21.5 |

22 |

22.5 |

23 |

23.5 |

24 |

24.5 |

25 |

25.5 |

26 |

26.5 |

27.5 |

28.5 |

29.5 |

30.5 |

31.5 |

Japan Men |

| Japan Ladies |

21 |

21.5 |

22 |

22.5 |

23 |

23.5 |

24 |

24.5 |

25 |

25.5 |

26 |

27 |

28 |

29 |

30 |

31 |

Japan Ladies |

| Mexico |

|

|

|

|

|

4.5 |

5 |

5.5 |

6 |

6.5 |

7 |

7.5 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12.5 |

Mexico |

| Australia & U.K. Men |

3 |

3½ |

4 |

4½ |

5 |

5½ |

6 |

6½ |

7 |

7½ |

8 |

8½ |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13½ |

Australia & U.K. Men |

| U.K. Women |

2½ |

3 |

3½ |

4 |

4½ |

5 |

5½ |

6 |

6½ |

7 |

7½ |

8½ |

9½ |

10½ |

11½ |

13 |

U.K. Women |

| Australia Women |

3½ |

4 |

4½ |

5 |

5½ |

6 |

6½ |

7 |

7½ |

8 |

8½ |

9½ |

10½ |

11½ |

12½ |

14 |

Australia Women |

| U.S. & Canada Men |

3½ |

4 |

4½ |

5 |

5½ |

6 |

6½ |

7 |

7½ |

8 |

8½ |

9 |

10½ |

11½ |

12½ |

14 |

U.S. & Canada Men |

| U.S. & Canada Women |

5 |

5½ |

6 |

6½ |

7 |

7½ |

8 |

8½ |

9 |

9½ |

10 |

10.5 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15.5 |

U.S. & Canada Women |

| Russia & Ukraine Women |

33½ |

34 |

|

35 |

|

36 |

|

37 |

|

38 |

|

39 |

|

|

|

|

Russia & Ukraine Women |

| Inches |

9 |

91/8 |

9¼ |

93/8 |

9½ |

95/8 |

9¾ |

97/8 |

10 |

101/8 |

10¼ |

10½ |

10¾ |

11 |

11¼ |

11½ |

Inches |

| Centimeters |

22.8 |

23.1 |

23.5 |

23.8 |

24.1 |

24.5 |

24.8 |

25.1 |

25.4 |

25.7 |

26 |

26.7 |

27.3 |

27.9 |

28.6 |

29.2 |

Centimeters |

| Mondopoint |

228 |

231 |

235 |

238 |

241 |

245 |

248 |

251 |

254 |

257 |

260 |

267 |

273 |

279 |

286 |

292 |

Mondopoint |

Girl's Shoe Sizes

| Europe |

26 |

26.5 |

27 |

27.5 |

28 |

28.5 |

29 |

30 |

30.5 |

31 |

31.5 |

32.2 |

33 |

33.5 |

34 |

35 |

Europe |

| Japan |

14.5 |

15 |

15.5 |

16 |

16.5 |

17 |

17.5 |

18 |

18.5 |

19 |

19.5 |

20 |

20.5 |

21 |

21.5 |

22 |

Japan |

| U.K. |

8 |

8.5 |

9 |

9.5 |

10 |

10.5 |

11 |

11.5 |

12 |

12.5 |

13 |

13.5 |

1 |

1.5 |

2 |

2.5 |

U.K. |

| U.S. & Canada |

9.5 |

10 |

10.5 |

11 |

11.5 |

12 |

12.5 |

13 |

13.5 |

1 |

1.5 |

2 |

2.5 |

3 |

3.5 |

4 |

U.S. & Canada |

Top of page

"Size Matters Not!" Sure... If you are Yoda. Otherwise, you need to use

a conversion table.

Size matters not. Look at me, judge me by my size do you, hmm? And well

you should not, for my ally is the Force and a powerful ally it is.

Boys shoe sizes

| Europe |

29 |

29.7 |

30.5 |

31 |

31.5 |

33 |

33.5 |

34 |

34.7 |

35 |

35.5 |

36 |

37 |

37.5 |

Europe |

| Japan |

16.5 |

17 |

17.5 |

18 |

18.5 |

19 |

19.5 |

20 |

20.5 |

21 |

21.5 |

22 |

22.5 |

23 |

Japan |

| U.K. |

11 |

11.5 |

12 |

12.5 |

13 |

13.5 |

1 |

1.5 |

2 |

2.5 |

3 |

3.5 |

4 |

4.5 |

U.K. |

| U.S. & Canada |

11.5 |

12 |

12.5 |

13 |

13.5 |

1 |

1.5 |

2 |

2.5 |

3 |

3.5 |

4 |

4.5 |

5 |

U.S. & Canada |

Notes

-

The Mondopoint system is the same as measuring in Millimeters (or Millimetres,

mm.). Some companies treat Mondopoint as Centimeters (Centimetres, cm.).

-

American Women's shoe sizes are the same as American Men's shoe sizes plus

1½.

-

Canadian shoe sizes are equivalent (identical) to American shoe sizes for

both Adult and Children's, Men and Women.

-

Mexican shoe sizes plus 1½ are the same as American Men's shoe sizes.

-

British shoe sizes plus 1 are the same as American Men's shoe sizes. However,

I see many tables using a formula of British size plus 1½. Check

with the manufacturer.

-

I saw one table on the web indicating British womens running shoe sizes

were 1.5 plus mens size. I think this is incorrect and mistakenly applied

the United States sizing rule to the U.K.

-

Japanese shoes sizes are American Men's shoes sizes plus 18. (Some companies

say add 19.)

-

Europe uses a system that came from the French called Paris Points (aka Parisien

Prick). One Paris Point equals two-thirds of a centimeter. The system

starts at zero centimeters and increases. There are no half sizes. American

size 0 is the same as 15 Paris Points.

-

1 Centimeter (Centimetre) is 10 Millimeters (Millimetres).

-

1 Inch is 2.54 Centimeters (Centimetres).

-

Length in Inches = 71/3 + (US Men's shoe size)*1/3

-

Paris Points = 311/3 + (UK shoe size)*4/3.

-

A Chinese 7 is a UK 4. That's all I know at the moment about sizes of shoes

in China.

-

Australia and New Zealand use the same shoe sizes as the United Kingdom

for boys, men and girls. However, I have seen women's shoe charts where

Australia is 1 or 2 sizes bigger than U.K... I added an entry with one

size bigger.

-

Korea measures shoe sizes in millimeters (mm.).

-

There are two scales used in the U.S. The standard (or "FIA") scale and

the common scales. The "common" scale is more widely used. The scales are

about ½ size different.

-

Although different kinds of shoes prefer different measurement systems,

I believe the charts work for all kinds of shoes. (With the caveat of the

variations mentioned above.) I have been looking into army, military, ski,

hiking, climbing boots, ladies pumps, high-heeled, spike and dress shoes,

as well as sneakers, designer shoes, gentlemen's shoes, causal, penny loafers,

sandals, and other styles. I have not been researching children's shoes

in much detail. The sizes above are also good for soccer, golf, running

and other sports shoes. I have not tried bowling shoes or blue suede sneakers.

I intend to get more detail on Nike, Reebok, and Adidas due to the strong

interest in running shoes for people coming to this page.

-

If you have information or can point me at information about additional

measurement systems of systems used by different countries I would be grateful.

(I am interested in Latin America and Eastern Europe.)

-

Russian and Ukraine shoe sizes taken from Global7Network.com

See that site for exact sizes in centimeters.

Men

| English |

4½ |

5 |

5½ |

6 |

6½ |

7 |

7½ |

8 |

8½ |

9 |

9½ |

10 |

10½ |

11 |

11½ |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

| US |

5½ |

6 |

6½ |

7 |

7½ |

8 |

8½ |

9 |

9½ |

10 |

10½ |

11 |

11½ |

12 |

12½ |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

| French |

37½ |

38 |

38½ |

39 |

40 |

40½ |

41 |

42 |

42½ |

43 |

44 |

44½ |

45 |

46 |

46½ |

47 |

48½ |

49½ |

51 |

| Japanese |

23½ |

24 |

24½ |

25 |

25½ |

26 |

26½ |

27 |

27½ |

28 |

28½ |

29 |

29½ |

30 |

|

|

|

|

|

Women

| English |

|

|

|

3 |

3½ |

4 |

4½ |

5 |

5½ |

6 |

6½ |

7 |

7½ |

8 |

8½ |

| US |

4 |

4½ |

5 |

5½ |

6 |

6½ |

7 |

7½ |

8 |

8½ |

9 |

9½ |

10 |

10½ |

11 |

| French |

34 |

34½ |

35 |

35½ |

36 |

37 |

37½ |

38 |

38½ |

39 |

40 |

40½ |

41 |

42 |

42½ |

| Japanese |

|

|

|

22 |

22½ |

23 |

23½ |

24 |

24½ |

25 |

25½ |

26 |

26½ |

27 |

27½ |

Children

| English |

2 |

3 |

4 |

4½ |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

8½ |

9 |

10 |

11 |

11½ |

12 |

13 |

13½ |

| US |

3 |

4 |

5 |

5½ |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

9½ |

10 |

11 |

12 |

12½ |

13 |

1 |

1½ |

| French |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

27 |

28 |

29 |

30 |

31 |

32 |

32½ |

| Japanese |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18 |

18½ |

19 |

19½ |

Teenagers

| English |

1 |

1½ |

2 |

2½ |

3 |

3½ |

4 |

4½ |

5 |

5½ |

6 |

6½ |

| US |

2 |

2½ |

3 |

3½ |

4 |

4½ |

5 |

5½ |

6 |

6½ |

7 |

7½ |

| French |

33 |

34 |

34½ |

35 |

35½ |

36 |

37 |

37½ |

38 |

38½ |

39 |

40 |

| Japanese |

20 |

20½ |

21 |

21½ |

22 |

22½ |

23 |

23½ |

24 |

24½ |

25 |

25½ |

Right-handed, Left-Footed

For most people, the larger foot is the opposite from the hand they write

with. Try on shoes starting with your larger foot.

Baum I & Spencer AM (1980) Limb Dominance: Its relationship to

Foot Length. J Am Pod. Assoc. 70(10): 505-507.

European size 217 men's shoe by Jozsef

Kovacs

European size 217 men's shoe by Jozsef

Kovacs

Shoe Width & Girth

Different shoe styles have different girths for the same shoe size, and

so do different shoe materials. Some manufacturers measure in width, some

in girth. Sometimes the difference is 1/4 inch, sometimes 3/16ths

of an inch and sometimes something else. The scale does not count upward

in a logical, incremental way, but uses letters:

AAAA (The narrowest)

AAA

AA

A

B

C

D

E

EE

EEE

EEEE (The widest)

No one knowswhy there isn't a BB or a CCC :-)

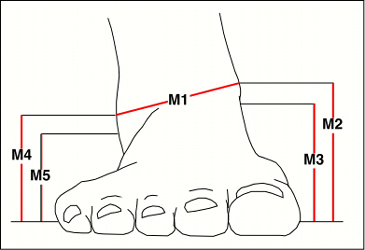

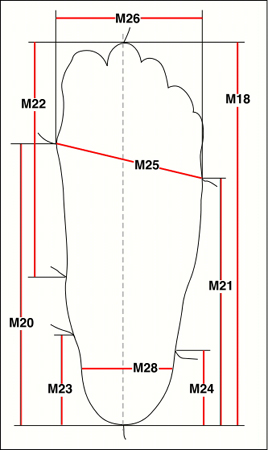

Foot measurements

from The National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology

Digital

Human Research Center, Japan

|

Abbreviation |

Measurement item |

| 1 |

M1 |

Bimalleolar breadth |

| 2 |

M2 |

Medial malleolus height |

| 3 |

M3 |

Sphyrion height |

| 4 |

M4 |

Lateral malleolus height |

| 5 |

M5 |

Sphyrion fibulare height |

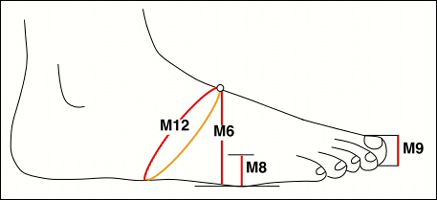

| 6 |

M6 |

Dorsal arch height |

| 7 |

M7 |

Ball height |

| 8 |

M8 |

Outside ball height |

| 9 |

M9 |

Great toe tip height |

| 10 |

M10 |

Great toe height |

| 11 |

M11 |

Foot circumference |

| 12 |

M12 |

Instep circumference |

| 13 |

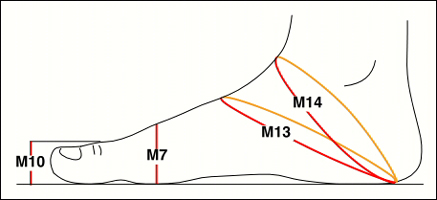

M13 |

Heel circumference |

| 14 |

M14 |

Diagonal ankle circumference |

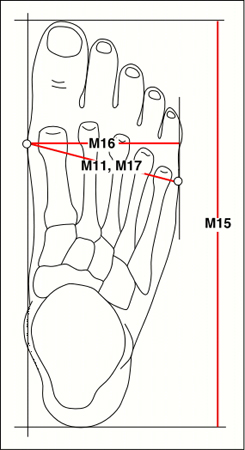

| 15 |

M15 |

Foot length |

| 16 |

M16 |

Foot breadth |

| 17 |

M17 |

Foot breadth, diagonal |

| 18 |

M18 |

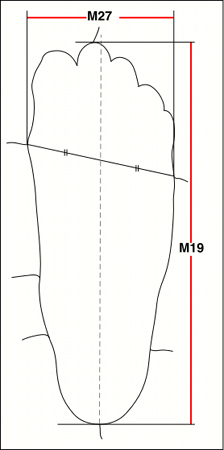

Foot length (JLIA) |

| 19 |

M19 |

Foot length (DIN) |

| 20 |

M20 |

Instep length |

| 21 |

M21 |

Fibular instep length |

| 22 |

M22 |

Back of foot length |

| 23 |

M23 |

Heel to medial malleolus |

| 24 |

M24 |

Heel to lateral malleolus |

| 25 |

M25 |

Foot breadth, diagonal (JLIA) |

| 26 |

M26 |

Ball breadth |

| 27 |

M27 |

Foot breadth (DIN) |

| 28 |

M28 |

Heel breadth |

| 29 |

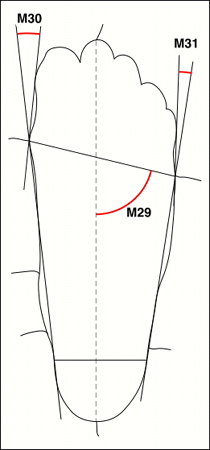

M29 |

Ball flex angle |

| 30 |

M30 |

Toe I angle |

| 31 |

M31 |

Toe V angle |

Is there an association between the use of heeled footwear and schizophrenia?

Jarl Flensmark, Medical Hypotheses

(2004) 63:740-747.

Existing etiological and pathogenetical theories

of schizophrenia have only been able to find support in

some epidemiological, clinical, and pathophysiological

facts. A selective literature review and synthesis

is used to present a hypothesis that finds support

in all facts and is contradicted by none.

Heeled footwear began to be used more than a 1000

years ago, and led to the occurrence of the first

cases of schizophrenia. Industrialization of shoe

production increased schizophrenia prevalence.

Mechanization of the production started in Massachusetts,

spread from there to England and

Germany, and then to the rest of Western Europe.

A remarkable increase in schizophrenia prevalence

followed the same pattern. In Baden in Germany the

increasing stream of young patients more or less

hastily progrediating to a severe state of cognitive

impairment made it possible for Kraepelin to

delineate dementia praecox as a nosological entity.

The patients continued to use heeled shoes after

they were admitted to the hospitals and the disease

progrediated.

High rates of schizophrenia are found among first-generation

immigrants from regions with a warmer

climate to regions with a colder climate, where

the use of shoes is more common. Still higher rates

among second-generation immigrants are caused by

the use of shoes during the onset of walking at an

age of about 11–12 months. Other findings point

to the importance of this in the later development of

schizophrenia. A child born in January–March begins

to walk in December–March, when it's cold

outside and the chances of going barefoot are smaller.

They are also smaller in urban settings.

During walking synchronised stimuli from mechanoreceptors

in the lower extremities increase activity

in cerebello-thalamo-cortico-cerebellar loops through

their action on NMDA-receptors. Using heeled

shoes leads to weaker stimulation of the loops.

Reduced cortical activity changes dopaminergic

function which involves the basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical-nigro-basal

ganglia loops. Bicycle riding

reduces depression in schizophrenia due to stronger

stimulation by improved lengthening contractions

of the triceps surae muscles. Electrode stimulation

of cerebellar loops normally stimulated by

mechanoreceptors in the lower extremities could

improve functioning in schizophrenia.

Cross-sectional prevalence studies of the association

between the use of heeled footwear and

schizophrenia should be made in immigrants from

regions with a warmer climate or in groups of

people who began to wear shoes at different ages.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is the most serious mental illness characterized

by disturbances of thought, behaviour

and mood appearing in young adults and by a deteriorating

course. Many etiological hypotheses have

been advanced, e.g., that schizophrenia is wholly

genetic, or that environmental factors such as

pregnancy or birth complications or early infections

are also important, but have not succeeded in

finding a correspondence between etiology, clinical

findings, course and outcome, brain pathology and

probable variations of prevalence. It is considered

to be either a developmental or a degenerative

disease, or a combination of both [1]. The diversity

of symptoms have been difficult to explain by a

unifying disease process [2].

History and epidemiology

The evolution of bipedal, plantigrade gait probably

occurred about ten million years ago. The first type

of shoe was a simple wraparound of leather, with

the basic construction of a moccasin. Although

sandals were the most common footwear in most early

civilizations, shoes were also worn. The oldest

depiction of a heeled shoe comes from Mesopotamia

[3], and in this part of the world we also find the

first institutions making provisions for mental

disorders. Possibly they and all the others that followed

were created because of the imperative need to care

for people affected by schizophrenia. Hospitals

with psychiatric divisions were created in Baghdad

(AD 750) and in Cairo (873). Special insane

asylums were built in Damascus (800), Aleppo (1270),

and in the Muslim-ruled Spanish city of

Grenada (1365) [4].

In Europe around 1400 we find Middle Eastern shoes

with a wedged sole, and cloglike overshoes

called pattens, which by then were wedge-shaped

at the back, raising the foot at the heel slightly

above the fore-part of the foot, and thus functioning

as heeled shoes. The creation of institutions for

the insane was also imported to Europe from the

Orient as hospitals with psychiatric divisions were

erected in Paris, Lyon, Munich, Basel, and Zurich

in the 13th century. Bethlehem hospital in London

began receiving the insane in 1377. The first Christian

European asylums were founded in Valencia