Walking as Art

Design

Disability Dolls

In 1997 toy-maker

Mattel hoped its wheelchair version of Barbie, called Becky, would help

change attitudes and stereotypes about the disabled, and help children

with disabilities build self-esteem. Barbie was introduced in 1959. And

Mattel says it's time her family became more inclusive.

In 1997 toy-maker

Mattel hoped its wheelchair version of Barbie, called Becky, would help

change attitudes and stereotypes about the disabled, and help children

with disabilities build self-esteem. Barbie was introduced in 1959. And

Mattel says it's time her family became more inclusive.

"We for quite some time have had ethnic diversity in Barbie's world,

but we were overdue in terms of really offering a friend who has a disability,"

said Nancy Zwiers, senior vice president for marketing.

While Mattel is

the largest toy-maker to market a disabled doll, it is not alone. Minnesota-based

Cultural Toys introduced a rag doll in 1995 in a wheelchair. Pleasant Company,

the Wisconsin toy company that makes the American Girl Collection, also

has a wheelchair accessory for its line of dolls. Fisher Price makes a

toy bus with a wheelchair ramp, and Little Tikes has a dollhouse with a

ramp, analysts said.

While Mattel is

the largest toy-maker to market a disabled doll, it is not alone. Minnesota-based

Cultural Toys introduced a rag doll in 1995 in a wheelchair. Pleasant Company,

the Wisconsin toy company that makes the American Girl Collection, also

has a wheelchair accessory for its line of dolls. Fisher Price makes a

toy bus with a wheelchair ramp, and Little Tikes has a dollhouse with a

ramp, analysts said.

Some features of Becky may be changed. For now, Becky's wheelchair won't

fit in most Barbie houses - even the elevator is too small. And unlike

real wheelchairs, Becky's has no seat belt, so she tumbles out easily.

Activists would like to see that changed.

"Everything they

can do to promote the whole accessibility of the world, to children, to

anyone with a disability, we want," said Patricia McGill Smith of National

Parent Network on Disabilities.

"Everything they

can do to promote the whole accessibility of the world, to children, to

anyone with a disability, we want," said Patricia McGill Smith of National

Parent Network on Disabilities.

Disabled groups don't care if Mattel makes money doing the right thing.

They're just happy to see the icon of physical perfection being used to

how that disabilities can be beautiful, too.

More recently, dolls with prostheses, Down

dolls and Chemo Friends (for children undergoing chemotherapy) have

been introduced.

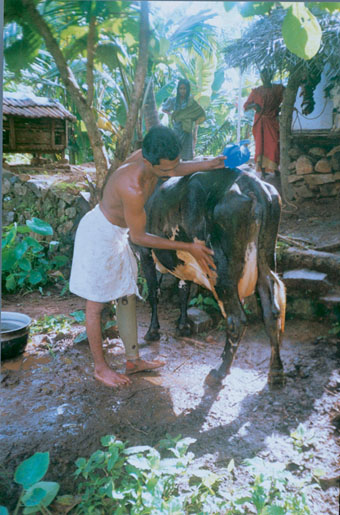

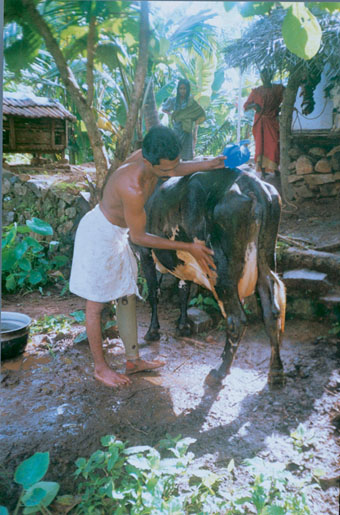

The

Jaipur Foot is used by thousands of people in India and Africa. The Jaipur

Foot is the result of a collaboration between P.K. Sethi, an orthopaedic

surgeon, and Ram Chander Sharma a craftsman

The

Jaipur Foot is used by thousands of people in India and Africa. The Jaipur

Foot is the result of a collaboration between P.K. Sethi, an orthopaedic

surgeon, and Ram Chander Sharma a craftsman

They

were concerned that people in India who had been fitted with western style

artificial limbs, at great cost to themselves, discarded them so Quickly

They realised that this type of prosthesis is not suitable for floor sitting

barefoot walking Indian people.

They

were concerned that people in India who had been fitted with western style

artificial limbs, at great cost to themselves, discarded them so Quickly

They realised that this type of prosthesis is not suitable for floor sitting

barefoot walking Indian people.

The Jaipur Foot is waterproof, cheap and looks good. It allows the user

to squat and sit cross-legged at floor level. Although the Jaipur Foot

was originally conceived as a solution to a local problem, it is now used

by many thousands of amputees, both on the Indian subcontinent as well

as in landmine countries affected by landmines such as Cambodia and Mozambique.

The photo shows the foot and ankle of the Jaipur leg in close-up. The

foot is dark flesh-coloured, while the leg above is silver. The toe nails

of the foot have been painted red, and the foot itself has been decorated

with red patterns. Around the ankle is a leather ankle bracelet, decorated

with a triple row of bells.

In front of the foot, and around the podium where the Jaipur limb is

displayed, artificial flowers are scattered. Within the exhibition, this

reflects the fact that a video about the Jaipur Limb Campaign is

playing nearby, featuring a dancer who performs Indian classical dance

while wearing a similar limb

Felicity Shillingford: My Left Boot

Felicity works in visual art, film and theatre, with actor/director

Garry Robson, producing for their company, 'Fittings Multimedia Arts'.

They make aids and adaptations used by an ever increasing number of people

in their daily lives.

Felicity and Garry first started looking at the design of disability

equipment for their touring exhibition 'Fittings: The Last Freakshow' which

was part exhibition and part performance.

Paul

is based in Bath and works for a

Paul

is based in Bath and works for a  company

that manufactures rickshaws, such as the pollution-free taxi type and custom

built bikes used for street theatre and performance.

company

that manufactures rickshaws, such as the pollution-free taxi type and custom

built bikes used for street theatre and performance.

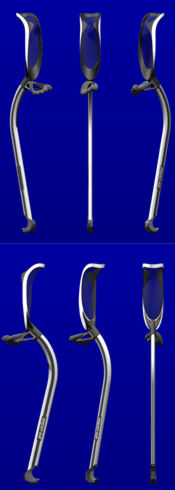

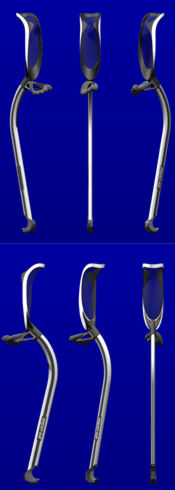

Pro-Carbon

Crutches were inspired by Guy Robinson’s first hand experience of trying

to lead an active life whilst using crutches.

Pro-Carbon

Crutches were inspired by Guy Robinson’s first hand experience of trying

to lead an active life whilst using crutches.

The design places crutches within the world of sport. Pro-Carbon Crutches

not only look good, they also work to reduce sports injuries

that might otherwise be inflicted by conventionally designed crutches.

They are made from silver and grey carbon. Unlike conventional crutches,

they curve backwards rather than being straight. They have silver lower-arm

supports which are made of fabric mesh, and grey hand supports where the

user puts their whole hand through the support and then grips a surface

which has been shaped to fit fingers. The feet are sprung, and resemble

the hooves of animals such as gazelles. Within the exhibition the crutches

are pictured, as only one prototype exists.

Sprung feet absorb impact, whilst the handles support central parts

of the hand that are sensitive to nerve damage. The forearm support is

a fabric mesh, that moulds itself to the forearm, and comfortably distributes

the load.

Guy is continuing his research on Pro-Carbon Crutches and on other prototypes

at the Royal College of Art. His crutches won the care award in ‘Design

for Our Future Selves’ competition, 2002.

Janie uses callipers

and crutches to walk. In May 2000 Tim and Janie were invited to redesign

a pair of her crutches, placing greater emphasis on individuality. Janie

has always used mass produced crutches, which she describes as “boring

and ugly” and has been frustrated by lack of choice and by the assumption

that “one design will suit everyone”.

Janie uses callipers

and crutches to walk. In May 2000 Tim and Janie were invited to redesign

a pair of her crutches, placing greater emphasis on individuality. Janie

has always used mass produced crutches, which she describes as “boring

and ugly” and has been frustrated by lack of choice and by the assumption

that “one design will suit everyone”.

Tim and Janie wanted the design to reflect Janie’s personality, and

to create crutches that could be used as a form of adornment. Janie wanted

to be able to show off her crutches, and wear them in a night club like

a piece of jewellery. The Couture Crutches are shaped from silver aluminium,

with black rubber handgrips and black shoulder supports. Rather than being

straight, they curve inwards between the shoulder supports and the hand

supports, before curving outwards and then in again at the feet. They are

very elegant.

Tim wanted to explore the fluid, twisting shapes found in human bones.

The shapes he created are both bold and engaging, and suggests that the

crutches form an extension of the skeleton. After consulting with Janie

on the final design, Tim cast the crutches into aluminium. Of her finished

crutches Janie says; “they are very sculptural, organic, eye catching,

and most importantly, unique, having a personality of their own, a very

far cry from my NHS crutches!”

Tim Register graduated in Fine Art (Sculpture) from Loughborough University

Janie Spencer is a part time art tutor, and artist based in Leicester.

She graduated in Fine Art from De Montfort University.

Nicola Lane’s installation explores how people see prosthetics both in

the past and currently. In her installation she brings together modern

prosthetics and both historical and contemporary photographs.

Nicola examines the past lives of prosthetic users by creating a sequence

of images, Edwardian photographs from the Science Museum Collection which

have been altered on a computer, to remove the prosthetic limb. The series

of images on the opposite wall show the absent prosthetic limbs. Nicola

makes us think about how the photographer saw these people, how they saw

themselves and how the rest of society saw these individuals.

Nicola arranged for filmmaker Tony Dowmunt to film our visit, and prosthetist

Ozan Altay also came. In the ScienceMu seum’s stores is their ‘Orthopaedic

Collection’, and with an amazing variety of prostheses, including Pre-N.H.S.

bespoke individualised limbs, N.H.S. experiments in electronically powered

limbs for Thalidomide children; 19th Century articulated steel and brass,

and best of all, a collection of

photographs, taken by an Edwardian prosthetist/orthotist of his clients

wearing their appliances, estimated to be in 1906, and all appear (with

one or two exceptions) to have been photographed in the same room, with

a painted backdrop and a patterned floor. In the installation, though,

these aids have been digitally removed from the photographs, leaving behind

their shape in grey. Another series of seven posters shows the aids themselves,

pictured against a grey background.

The second part of the installation consists of a series of four poster-sized

photographs. Each shows an historical artificial limb, made between the

eighteenth and early twentieth century, photographed against a brightly

coloured background. The silicon leg covers used in the installation are

designed to look as real as science allows. Again Nicola is concerned about

the gap between appearances and how things really are. These leg covers

are just for appearance, and do not function as real prosthetics.

Nicola does not believe that cosmesis, the appearance of prosthetics

should be separated from the function of a prosthetic. She believes that

alternatives such as the Jaipur foot are more truly inclusive for the user.

They represent function as cosmesis.

By emphasising function, comfort and ease of use, Nicola claims that

cosmesis should be about how the user feels about their prosthetic. Not

how the viewer feels looking at it. By separating the prosthetics from

the figures, Nicola is inviting the viewer to imagine what prosthetic they

would like to wear.

Aesthetics

and design never seem to be where disabled people want them in the list

of priorities. In architecture and building design, aesthetics so often

override function that access usually gets created as an afterthought,

bolted on against the disapproval of the style-driven architects. Disabled

people in public buildings curse and battle against slippery floors, cavernous

acoustics, weighty doors and perspex signposts – designed for aesthetics,

not for function.

Aesthetics

and design never seem to be where disabled people want them in the list

of priorities. In architecture and building design, aesthetics so often

override function that access usually gets created as an afterthought,

bolted on against the disapproval of the style-driven architects. Disabled

people in public buildings curse and battle against slippery floors, cavernous

acoustics, weighty doors and perspex signposts – designed for aesthetics,

not for function.

Yet when it comes to the everyday items which disabled people must have,

their clothes, homeware and mobility aids, the exact opposite seems to

apply. We are provided with items that can be easily mass-produced, cleaned

or stacked in a cupboard by a nurse or carer, and not what we would choose

to wear or carry.

Aluminium, rubber and a curious bakelite plastic in grey or flesh-tones

are the materials we get handed. The welter of colour, choice and subliminal

pressure applied to the consumer in every other case passes us by.

The message we get is clear – design is not for us. Concepts like opinion,

taste, choice, pleasure and excitement are absent in the provision made

for what we need. A direct opposition is set up between the ideas of "need"

and "want". It is a moral lesson – beggars can’t be choosers, and disabled

people are very evidently cast in the role of beggar.

It wasn’t always so. Social history collections in museums show us that

the moneyed disabled person used to be able to commission craftworks that

served their needs – exquisitely carved wheeled chairs, the candy-twists

of Venetian glass walking canes, hand-embroidered waistcoats which disguised

the bodies of rich men with spinal curvature. Even if you weren’t rich,

before mass-production became ordinary, it would not have been so difficult

to make a jacket that fitted

short arms, or a missing limb. Your one pair of boots would have been

made for you, your chair the height you needed to reach the

table.

Disabled people were the cast-offs after standardisation in the 20th

century, when difference became bad, and average a word of

approval. Manual crafts and personalisation were marginalised in favour

of the ‘one-size-fits-all’ lie. Ergonomics invented an

acceptable range of difference around the design of cars, cookers and

school desks, and within which short, fat or one-legged people

didn’t fit. It’s considered shocking in this context to claim that

normality is, in fact, an exception – that most of us are abnormal.

Not far beneath the surface of each collaboration in this exhibition

lie the ghosts of a more responsive past – 500 workmen bending

over wooden benches in a limb-fitting centre, the secret clay pigments

of the Arizona desert which created flesh-toned prostheses,

walking sticks which contained brandy for tedious social events or

poisoned darts for your enemies. The artists, makers and

designers involved in adorn, equip have come to see disabled people

as personalities and tried to serve them in a way which

creates not just comfort but the thrill of ownership, fun and status.

What’s new for the 21st Century is the acknowledgment of

feelings – of fear and challenge, insecurity and isolation – which

can be addressed with accessories and aids which are desirable

and worth showing off. Their solutions might not fit in every household

– but that’s part of the point. What they offer is an answer

which suits individuals with specific combinations of need, choice,

want and taste – because, guess what? All of these consumer

desires exist in every disabled person who wants to adorn or equip

themselves.

Go Go

Gadget Wheelchair: Fit, Form and Desire

The

Go Go Gadget Wheelchair is silver and imposing and

The

Go Go Gadget Wheelchair is silver and imposing and

cannot be ignored: its user will always be visible, however hard passers-by

try to ignore them - particularly given the flashing hazard

lights. And if onlookers are abusive, there is always the boxing glove

on a

spring, or in extreme cases, the rocket which is mounted on the side.

Or

the user can ignore them and choose instead to turn on the radio, use

the

camera or simply have a drink of whisky.

Mountain bike wheels state that the user intends to go everywhere,

without restraint, and a helicopter-like propeller shows how this will

be

managed in the face of obstructions like steps and kerbs. The speed

of

the chair is unhampered by social workers’ fears that disabled people

will run riot and cause accidents if we travel at more than five miles

an

hour: aircraft engines are mounted on each side of the chair, while

a

platform at the back allows a companion to ride along when they are

unable to keep up on foot. A grappling hook can be thrown out

anchor-like to stop the chair, or to retrieve objects that are otherwise

inaccessible.

And the user of such a chair can only be a superhero - not invisible

and

denied full civil and human rights, “bravely” negotiating a disabling

world, as wheelchair users in this country are today. In real life,

though,

disabled people do not want to seen as heroic - just as being “normal”,

with it being normal to include us fully in every part of life, and

to create

an environment which allows for this.

How can a wheelchair be an object of desire? It is more commonly portrayed

as an object of horror and disgust, and the need to use it as a tragedy.

We all recognise the newly disabled character in film and television -

generally played by a non-disabled actor - who detests their wheelchair

and wants nothing more than to

get out of it, sometimes choosing to die instead if this is not a possibility.

The language that we use to refer to wheelchair users is equally

unhelpful. Non-disabled people talk of someone “being in a wheelchair

for 15 years” - as if wheelchair users do not leave their chairs every

day

to sleep, bathe, use the toilet, drive, or just to join the rest of

the family

on the settee in front of the television in the evening. And non-disabled

people frequently refer to full-time wheelchair users (one in twenty

of all

wheelchair users) as being “confined” to their wheelchairs, as if the

chair

is an object of imprisonment rather than of liberation.

Of

course, many of the wheelchairs supplied to disabled people by the

Of

course, many of the wheelchairs supplied to disabled people by the

State in the form of social services or the NHS are disabling in

themselves: these chairs are often badly designed, ugly, uncomfortable,

and difficult or impossible to use independently. My own NHS

“self-propelling” wheelchair was difficult for anyone to lift into

a

car, increased my pain levels because it provided no proper spinal

support for me, and was in fact to heavy to propel independently. Who

indeed would welcome one of these into their lives?

But when a wheelchair does fit us, when its form does suit us, when

its

design does meet fully with our desires, then it is the most liberating,

desirable means of transport for people with mobility impairments of

every kind. Suddenly we can sit comfortably and move wherever we

wish for as long as we wish at the touch of a button or the flick of

a

wheel: we are free.

The

new self-propelling wheelchair, made by RGK and supplied by the Wheelchair

Warehouse, is a genuine object of desire. Manufactured largely from titanium

and leather, it was custom-made. But its purchase was made possible only

by the Government’s Access to Work Scheme - desirable wheelchairs which

empower our independence are expensive, while disabled people have the

lowest incomes of anyone in the country. Despite the language of “social

inclusion”, desirable wheelchairs are not considered to be necessary for

us to live independently, only to work.

The

new self-propelling wheelchair, made by RGK and supplied by the Wheelchair

Warehouse, is a genuine object of desire. Manufactured largely from titanium

and leather, it was custom-made. But its purchase was made possible only

by the Government’s Access to Work Scheme - desirable wheelchairs which

empower our independence are expensive, while disabled people have the

lowest incomes of anyone in the country. Despite the language of “social

inclusion”, desirable wheelchairs are not considered to be necessary for

us to live independently, only to work.

Equally, the popular image of the wheelchair prevails, and as a result,

many people who would benefit from using a wheelchair either refuse,

or are refused permission, to do so. The goal is to appear “normal”

-

without impairments - as if having a mobility impairment is not normal,

and as if we will not all have impairments of some kind over the course

of our lifetimes. Thus people who have great difficulty in walking

are still

denied or deny themselves access to wheelchairs, and have far narrower,

harder lives as a result.

This attitude is propagated at the highest levels of our society. The

Pope

and the Queen Mother, both old enough to know better, refused to be

seen in public using wheelchairs, preferring to be be viewed as immobile

and dependent. Perhaps it is unsurprising, then, that so many other

older

people within our society are leading restricted and difficult lives

rather

than use a wheelchair. Meanwhile physiotherapists continue to teach

disabled people that wheelchair use is a sign of failure, to be avoided

if at

all possible even if the alternative is pain and immobility.

The irony, of course, is that many non-disabled people in the United

Kingdom rarely walk at all - they sit down and drive their children

to

school; they sit down and drive to the shops; they sit down and drive

to

work; they sit down and drive to see their friends - even when all

of

these activities take place within five miles of their homes. And then

they

come home and sit down in front of the television until it is time

to go to

bed. That would have been unthinkable in this country during the first

half of the twentieth century, and remains unthinkable in many countries

worldwide today.

And yet, despite the billions of pounds which are spent on roads to

facilitate the use of private cars, and the massive changes to the

environment that this causes, no one questions this as being “normal”.

It

is both “normal” to walk, and at the same time it is “normal” for those

who can walk to choose NOT to walk. Indeed, it is desirable not to

walk

if you CAN walk easily: a car signifies status and power; while walking

signifies poverty.

If someone needs to use a wheelchair in order to live their life as

fully as

possible, though, everything changes. It is “normal” to build roads,

and

then to install speed humps, but it is not regarded as “normal” to

create

regular dropped kerbs to allow wheelchair users, parents with buggies

etc to cross those roads easily. It is “normal” to build steps rather

than

ramps; it is not regarded as “normal” to install lifts instead of or

as well

as staircases. In fact, it is “normal” to make the built environment

difficult or impossible for all of us to access at some point in our

lives, as

if we only deserve to participate fully in society when we can walk

(even

if we normally choose to drive instead).

Convertible High Heels

High heels are the only acceptable form of shoe for females on a formal

occasion, and are almost mandatory in a business power dressing, yet they

are very uncomfortable and casue long term health issues. How many times

have you seen women walking to work in sensible shoees carrying high heels

in their handbag? A new design for adjustable high heels could solve the

problem. This shoe solution converts a high 7 cm heel to a low 3 cm heel

with one simple twist on/off action.

North Sydney UTS student Sophie Cox's idea came to her when she wrote

a Research Dissertation Paper for her university of technology Studies

in 2003 on the subject of the physical effects of high heels on women.

The concept of the CONVERTIBLES (Adjustable High Heels) came from researching

the paper.

“I was horrified when I looked into the physical problems which

high heels cause in women. In many ways, it is a modern western form of

the Japanese foot-binding, where a social or cultural tradition creates

long term health problems.”

“It’s unfortunate, but high-heeled footwear creates prolonged

problems for wearer’s feet, back and knees.

“On the other hand, high heels now play a very complex role in modern

society and have become the only shoe accepted for women on formal occasions

and the shoe of choice for women in business when they’re in ‘power dressing’

mode.”

“There’s no question that when you put on a set of heels, you feel great.

It’s a psychological thing, but when you’re working long hours in an office,

you need comfortable attire. So sometimes, say, several times a day, you

want your full high heels, and the rest of the time you want comfortable

shoes.

The design of the heels flowed from there but it’s always been a subject

close to Sophie’s heart. As I went through school, I was never quite sure

where I would end up – I wanted at different times to go into fashion,

sculpture and I’ve always had a thing about shoes, and when it came time

to specialise, I thought that the ralm of industrial design gave me the

opportunity to express it all.

Bernard Rudofsky: Unfashionable Human Body

Trousers shape the leg so it appears as a tubular appendage. Author Bernard

Rudofsky writes this about the trouser: "The trinity of thigh, knee and

calf, each marvelously molded and replete with eye and sex appeal, is stuck

into a cylinder . . . but fails to do justice to a live one."

The Power Assist Suit was developed at Kanagawa to aid nurses in lifting

immobile patients. Electronic sensors monitor the user’s muscles and trigger

the hydraulically operated suit to boost strength by more than 50%. The

aging world population is seen as an affluent target market for carer and

helper robotic applications.

In a push to turn the science fiction of exoskeletons - like the one used

by Sigourney Weaver in

Aliens - into a military reality and deliver the advantages of such technology

to soldiers in combat

environments, the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA),

is funding a

US$50 million project known as "Exoskeletons

for Human Performance Augmentation". The

scope of the program includes the development of actively controlled exoskeletons

that not only

increase strength and speed, but enable larger weapons to be carried, provide

a higher level of

protection from enemy fire or chemical attack, allow wearers to stay active

longer and carry

more food, ammunition and field supplies. Exoskeletons may eventually even

be programmed to

bring injured soldiers back to base by themselves. Systems will range from

un-powered

mechanical devices that assist a particular aspect of human function to

fully-mechanised

exoskeletons relying on chemical or hydrocarbon fuels for totally independent

operation by

soldiers in the field.

Several different projects under the DARPA umbrella are underway including

SARCOS

Research Corporation's Wearable Energetically Autonomous Robots (WEAR).

Designed for

on-foot combat, WEAR will include a base unit configured like legs, torso

and arms that mimic

human movement using complex kinematic systems and contain energy storage,

power systems,

actuators and everything needed for an autonomous wearable system. ASP's

(Application-Specific Packages) will provide additional protection against

specific threats like

radiation and biological agents or give expanded functionality for communications,

surveillance or

night operations. SARCOS is on track to have a legs only version of the

exoskeleton ready for

trial by 2003 and a working full-body prototype is expected around 2005.

The problems of actuation, power supply and energy storage are being tacked

on several fronts

with M-DOT Aerospace working on a META (Mesoscopic Turboalternator) engine

capable of

acting as a viable electric power source for human exoskeletons and Quoin

International

developing a unique power supply and actuation system for anthropomorphic

exoskeletons using

hydrocarbon fuels and high-pressure pneumatic systems to mimic human movement.

The Berkeley Lower Extremity Exoskeleton, or Bleex, is part of a US

defence project designed to be used mainly by infantry soldiers.

The device consists of a pair of mechanical metal leg braces including

a power unit and a backpack-like frame.

More than 40 sensors and hydraulic mechanisms calculate how to distribute

weight just like the nervous system.

These help minimise the load for the wearer.

A large rucksack carried on the back contains an engine, control system

and space for a payload.

"There is no joystick, no keyboard, no push button to drive the device,"

said Homayoon Kazerooni, director of the Robotics and Human Engineering

Laboratory at the University of California.

The Bleex exoskeleton has a small, purpose-built combustion engine built

into it. On a full tank the system should be able to run for up to two

hours.

The device's leg braces are attached to a modified pair of army boots

and connected to the user's legs.

In the lab, subjects have walked around in the 45kg (100lbs) exoskeleton

plus a 31.5kg (70lbs) backpack and reported that it felt like they were

carrying little over 2kg (5lbs).

"The design of this exoskeleton really benefits from human intellect

and the strength of the machine," said Dr Kazerooni.

The project has been funded by the US Defense Advanced Research Projects

Agency (Darpa).

1

kW/leg Servo Assist

1

kW/leg Servo Assist

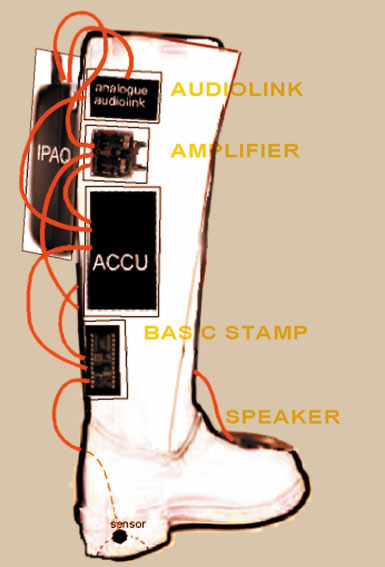

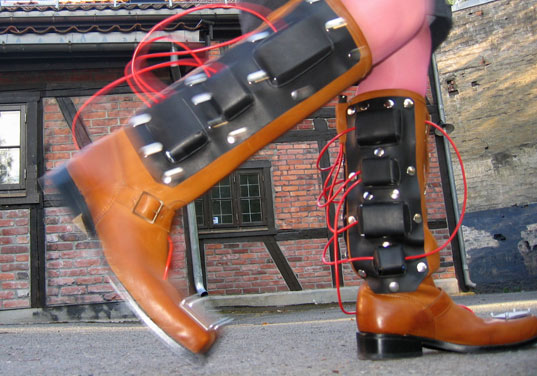

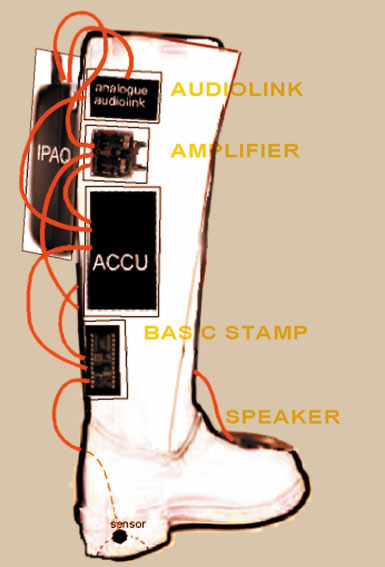

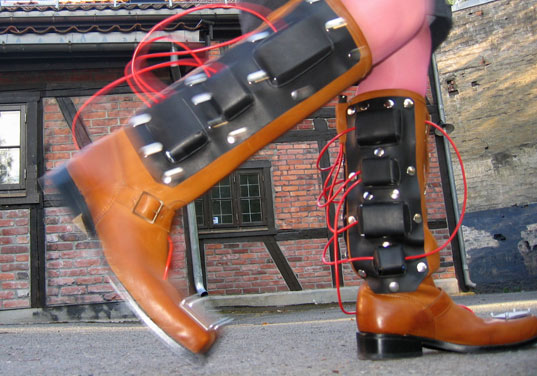

Sitting somewhere between performance and experiential art, Seven Mile

Boots are interactive shoes with audio. One can wear the boots, and walk

around simultaneousy in the physical world and in the literal world of

the internet. By walking in the physical world one may suddenly encounter

a group of people chatting in real time in the virtual world. The chats

are heard as a spoken text coming from the boots. The concept is that whenever

you wear the boots, the physical and the virtual worlds will merge together.

The seven-mile-boots are intended as an interface to move within this text-based

non-space of the chatrooms. The boots have two different modes; walking

through the net and standing/ listening/ observing the chat-activity.

When walking, the boots seek a new selection of channels from the net.

The boots contain all the necessary technology and the user does not control

or influence the experience - there's a computer with wireless network,

sensors, amplifiers and loudspeakers. The boots are ready to function in

any location with an open wireless network, though poresumably you'll need

some sort of filter for public places where the chat room contents may

not be suitable to be read aloud by your boots in a public place. The boots

are intended to shift the viewpoint from the physical to the conceptual,

focusing on the ordinary everyday activities and desires of people and

offer a perspective into the processes, which are an inherent part of our

current lifestyle.

When the user is wearing the seven-mile-boots and standing still s/he

can listen several chat rooms simultaneously becoming a super-voyeur, and

able to search in several places and observe various situations simultaneously

in the net. After putting on the boots they start looking for active chat

channels. When the user walks around s/he can locate a chat activity through

audio. S/he will hear himself passing through a group of chatters or s/he

can decide to stop for closer observation. The boots log into the chat

rooms automatically under the name of "sevenmileboots".

Maxwell Smart's Shoe Phone (Get Smart)

Operator: "What number are you calling?"

Smart: "I'm calling Control, Operator…"

Operator: "You have dialed incorrectly. Give

me your name and address and your dime will

be refunded."

Smart: "Operator, I'm calling from my shoe!"

Operator: "What is the number of your shoe?"

Smart: "It's an unlisted shoe, Operator!"

Maxwell Smart, Agent 86 of Control, cleverly housed a telephone in his

shoe. As used for five seasons by Don Adams in the Emmy-winning comedy

series, the Shoe Phone has earned a permanent place in our memories, our

hearts, and especially our funny bones, as a classic icon of popular culture.

CIA Spy Shoe with Heel Transmitter

Looking like a quirky

prop from Get Smart, the 1960's KGB issue Spy Shoe with a radio transmitter

concealed in the heel was used to monitor secret conversations. The shoe's

transmitter, microphone, and batteries were imbedded in the heel of a target's

shoe. A maid or valet with access to the individual's clothing would be

given the job of planting the rigged shoes and activating the transmitter

by pulling out a white pin from the heel. The target would then become

a walking radio station, transmitting all conversations to a nearby monitoring

post.

Looking like a quirky

prop from Get Smart, the 1960's KGB issue Spy Shoe with a radio transmitter

concealed in the heel was used to monitor secret conversations. The shoe's

transmitter, microphone, and batteries were imbedded in the heel of a target's

shoe. A maid or valet with access to the individual's clothing would be

given the job of planting the rigged shoes and activating the transmitter

by pulling out a white pin from the heel. The target would then become

a walking radio station, transmitting all conversations to a nearby monitoring

post.

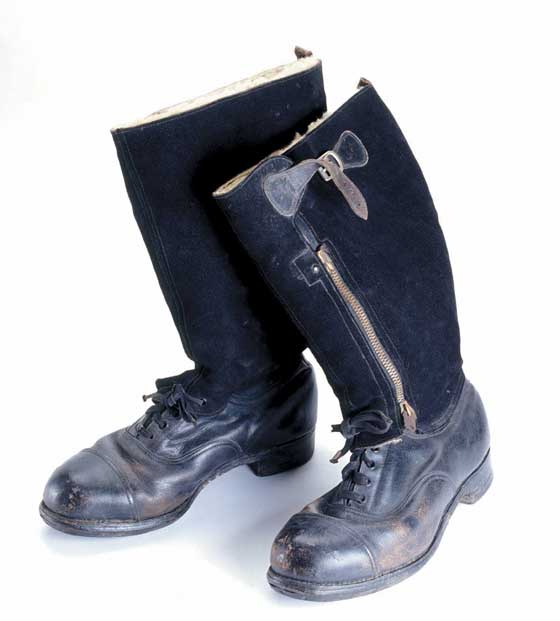

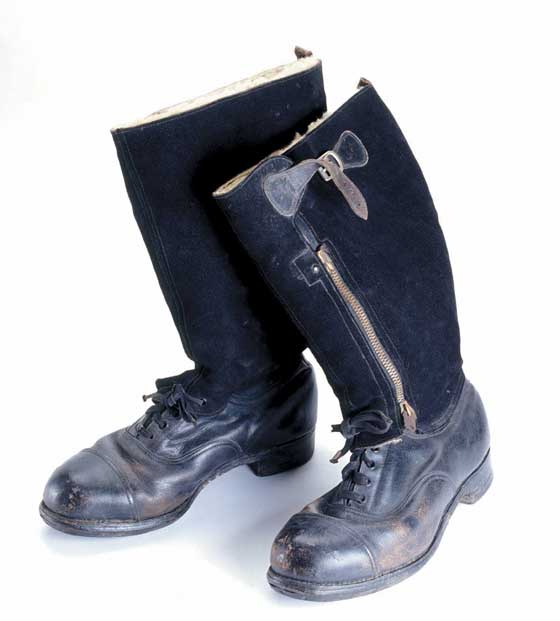

Escape Boots

These English MI9 issue boots were designed for British pilots trying

to escape detection in enemy territory. A small pen-knife concealed in

the boots was used to cut off the tops so that they looked like civilian

walking shoes rather than easily recognisable "flying boots".

Wenzhou, Shoe and Sock-making Capital of China

As far back

as the Southern Song Dynasty

As far back

as the Southern Song Dynasty

(1127-1279) there were professional shoe-makers in

Lucheng. Wenzhou is where China's first pigskin,

sulfide leather, and molded leather shoes were made.

Among China's six most famous brands of shoes, three

-- Kangnai, Dongyi and Jierda -- are from Lucheng. As

Wenzhou's pillar industry, the shoe-making sector

encompasses over 4,000 enterprises, yielding an annual

output value of 30 billion yuan, and an export value of 6

billion yuan. Wenzhou indubitably leads China's

shoe-making industry.

On Woqi Mountain by the Oujiang River in Wenzhou stands the city's landmark

building --

China Shoe Capital Culture Museum. The first modern shoe museum in the

country, it houses

more than 2,000 exhibits dating from Neolithic to modern times, and includes

many rare items.

The Shoe Capital Industrial Park, currently under construction, is the

future site of Wenzhou's

largest and most well reputed shoe-making enterprises. Occupying an area

of 6.5 square

kilometers, scientific research, trading, information exchange and manufacture

are to be

conducted at this large shoe production base. It is expected to become

the world's largest

shoe-making center.

As the local leather-shoe-making sector flagship, Kangnai has set up 33

outlets in Europe and

North America, and has registered its trademark in 36 countries and regions.

In order to make

itself an international brand Kangnai employs Italian shoe designers.

Pop culture seems to share this shoe fetish; rappers in particular are

calling a lot of attention to

their footwear. Reebok has recruited all the top urban icons as pitchmen:

Jay-Z has the S.

Carter line; 50 Cent has the G-Unit; Pharrell Williams has just released

the Ice Cream collection.

Nelly has a song solely dedicated to hyping Nike's Air Force Ones. There's

even been a rash of

books published on the subject, including DJ Bobbito's Where'd You Get

Those? New York City's

Sneaker Culture: 1960-1987 (Powerhouse Books, 2003). How did gym shoes

get to be so huge?

Where is this widespread obsession with sneakers coming from?

At the Vancouver International Hip-Hop Film Festival this September, one

documentary,

Sneakers, offered some insight. Netherlands director Femke Wolting tracked

the progression of

the sneaker from functional sportswear to a marker of cultural identity.

He interviewed shoe

historian Scoop Jackson, who believes that American ghettos inspired the

global sneaker

explosion. Young black men in the inner city experienced low employment

rates and had little

spending money, Jackson argues. With no jobs to dress up for and limited

funds, they made

cheap basketball shoes like Converse the footwear of choice.

As time went on, running shoes became a status symbol. Sporting brand-new

designer kicks

demonstrated that one was moving up; conspicuous consumerism was a way

of asserting

identity in the face of harsh economic and social realities. When hip-hop

artists exploded onto

the international stage, they transformed sneakers into high fashion. The

track "My Adidas", for

instance, saw Run-DMC popularize 'hood style and skyrocket sales for the

shell-toed shoe. When

Michael Jordan teamed up with Nike for the Air Jordan, sneaker culture

hit the mainstream in a

big way. The shoe was so highly anticipated that it had a release date,

just like an album.

Nowadays, sneaker enthusiasts all over the world have massive collections

that keep eBay in

business. A select group of Vancouver hip-hop heads has always been up

on kicks, but the

sneaker-freak culture here is growing exponentially, and a new store has

recently opened in

Gastown to serve this demographic.

Livestock (239 Abbott Street) is the brainchild of Garret

Louie (aka G-Man), urban music

promoter, DJ, and long-time sneaker collector. Louie's day job is co-owner

of Timebomb Trading,

a skateboard, snowboard, and streetwear distribution company. Over the

past 15 years, he has

travelled extensively for work, hitting major sneaker spots in Japan, New

York, Los Angeles, and

London, and picking up hundreds of pairs along the way. Louie decided this

year that Van City

was ready for a serious sneaker boutique. He teamed up with Kenta Kimura,

Garry Bone, and

Robert Rizk to open Livestock, which is one of a handful of stores in North

America that carries

such desirable, collectible sneakers.

Deadstock is a term for shoes that have never been worn and

that are still in the box with their

original laces. These shoes are the most valuable to collectors. Louie

and company decided that

they wanted to emphasize enjoyment. "We said, 'Screw keeping them in the

box, even though

they could be worth $500 down the road,' " he explains, interviewed recently

at the shop. "We

said, 'Let's call it Livestock. Let's wear the shoes: skateboard in them,

b-boy in them, wear them

to the club.' "

The store is beautifully designed, with a minimalist modern vibe. Dozens

of carefully selected

shoes line the walls. (Prices range from $60 to $300.) Louie walks me around,

pointing out

favourites and imparting design and history tips. Many of the shoes are

packaged in bundles: a

baseball pack has soft glove leather; a World Cup soccer pack features

the colours of national

flags; a Navigation pack has maps of the big sneaker collecting cities

laser cut onto leather

panels. One of the hot lines right now is Japanese designer Nigo's Bathing

Ape brand.

The store balances its stock between rare finds and more traditional fare.

It focuses on

expanding the culture through sponsoring hip-hop shows and art events,

and encouraging

budding sneaker heads. "We don't want to be that shop that cops an attitude

that's too cool for

school," Louie says. "Everyone was starting in this culture at one time.

We're totally cool with

educating people."

While Mattel is

the largest toy-maker to market a disabled doll, it is not alone. Minnesota-based

Cultural Toys introduced a rag doll in 1995 in a wheelchair. Pleasant Company,

the Wisconsin toy company that makes the American Girl Collection, also

has a wheelchair accessory for its line of dolls. Fisher Price makes a

toy bus with a wheelchair ramp, and Little Tikes has a dollhouse with a

ramp, analysts said.

While Mattel is

the largest toy-maker to market a disabled doll, it is not alone. Minnesota-based

Cultural Toys introduced a rag doll in 1995 in a wheelchair. Pleasant Company,

the Wisconsin toy company that makes the American Girl Collection, also

has a wheelchair accessory for its line of dolls. Fisher Price makes a

toy bus with a wheelchair ramp, and Little Tikes has a dollhouse with a

ramp, analysts said.

In 1997 toy-maker

Mattel hoped its wheelchair version of Barbie, called Becky, would help

change attitudes and stereotypes about the disabled, and help children

with disabilities build self-esteem. Barbie was introduced in 1959. And

Mattel says it's time her family became more inclusive.

In 1997 toy-maker

Mattel hoped its wheelchair version of Barbie, called Becky, would help

change attitudes and stereotypes about the disabled, and help children

with disabilities build self-esteem. Barbie was introduced in 1959. And

Mattel says it's time her family became more inclusive.

"Everything they

can do to promote the whole accessibility of the world, to children, to

anyone with a disability, we want," said Patricia McGill Smith of National

Parent Network on Disabilities.

"Everything they

can do to promote the whole accessibility of the world, to children, to

anyone with a disability, we want," said Patricia McGill Smith of National

Parent Network on Disabilities.

The

Jaipur Foot is used by thousands of people in India and Africa. The Jaipur

Foot is the result of a collaboration between P.K. Sethi, an orthopaedic

surgeon, and Ram Chander Sharma a craftsman

The

Jaipur Foot is used by thousands of people in India and Africa. The Jaipur

Foot is the result of a collaboration between P.K. Sethi, an orthopaedic

surgeon, and Ram Chander Sharma a craftsman

They

were concerned that people in India who had been fitted with western style

artificial limbs, at great cost to themselves, discarded them so Quickly

They realised that this type of prosthesis is not suitable for floor sitting

barefoot walking Indian people.

They

were concerned that people in India who had been fitted with western style

artificial limbs, at great cost to themselves, discarded them so Quickly

They realised that this type of prosthesis is not suitable for floor sitting

barefoot walking Indian people.

Paul

is based in Bath and works for a

Paul

is based in Bath and works for a  company

that manufactures rickshaws, such as the pollution-free taxi type and custom

built bikes used for street theatre and performance.

company

that manufactures rickshaws, such as the pollution-free taxi type and custom

built bikes used for street theatre and performance.

Pro-Carbon

Crutches were inspired by Guy Robinson’s first hand experience of trying

to lead an active life whilst using crutches.

Pro-Carbon

Crutches were inspired by Guy Robinson’s first hand experience of trying

to lead an active life whilst using crutches.

Janie uses callipers

and crutches to walk. In May 2000 Tim and Janie were invited to redesign

a pair of her crutches, placing greater emphasis on individuality. Janie

has always used mass produced crutches, which she describes as “boring

and ugly” and has been frustrated by lack of choice and by the assumption

that “one design will suit everyone”.

Janie uses callipers

and crutches to walk. In May 2000 Tim and Janie were invited to redesign

a pair of her crutches, placing greater emphasis on individuality. Janie

has always used mass produced crutches, which she describes as “boring

and ugly” and has been frustrated by lack of choice and by the assumption

that “one design will suit everyone”.

Aesthetics

and design never seem to be where disabled people want them in the list

of priorities. In architecture and building design, aesthetics so often

override function that access usually gets created as an afterthought,

bolted on against the disapproval of the style-driven architects. Disabled

people in public buildings curse and battle against slippery floors, cavernous

acoustics, weighty doors and perspex signposts – designed for aesthetics,

not for function.

Aesthetics

and design never seem to be where disabled people want them in the list

of priorities. In architecture and building design, aesthetics so often

override function that access usually gets created as an afterthought,

bolted on against the disapproval of the style-driven architects. Disabled

people in public buildings curse and battle against slippery floors, cavernous

acoustics, weighty doors and perspex signposts – designed for aesthetics,

not for function.

The

Go Go Gadget Wheelchair is silver and imposing and

The

Go Go Gadget Wheelchair is silver and imposing and

Of

course, many of the wheelchairs supplied to disabled people by the

Of

course, many of the wheelchairs supplied to disabled people by the

The

new self-propelling wheelchair, made by RGK and supplied by the Wheelchair

Warehouse, is a genuine object of desire. Manufactured largely from titanium

and leather, it was custom-made. But its purchase was made possible only

by the Government’s Access to Work Scheme - desirable wheelchairs which

empower our independence are expensive, while disabled people have the

lowest incomes of anyone in the country. Despite the language of “social

inclusion”, desirable wheelchairs are not considered to be necessary for

us to live independently, only to work.

The

new self-propelling wheelchair, made by RGK and supplied by the Wheelchair

Warehouse, is a genuine object of desire. Manufactured largely from titanium

and leather, it was custom-made. But its purchase was made possible only

by the Government’s Access to Work Scheme - desirable wheelchairs which

empower our independence are expensive, while disabled people have the

lowest incomes of anyone in the country. Despite the language of “social

inclusion”, desirable wheelchairs are not considered to be necessary for

us to live independently, only to work.

SpringWalker

SpringWalker 1

kW/leg Servo Assist

1

kW/leg Servo Assist

Looking like a quirky

prop from Get Smart, the 1960's KGB issue Spy Shoe with a radio transmitter

concealed in the heel was used to monitor secret conversations. The shoe's

transmitter, microphone, and batteries were imbedded in the heel of a target's

shoe. A maid or valet with access to the individual's clothing would be

given the job of planting the rigged shoes and activating the transmitter

by pulling out a white pin from the heel. The target would then become

a walking radio station, transmitting all conversations to a nearby monitoring

post.

Looking like a quirky

prop from Get Smart, the 1960's KGB issue Spy Shoe with a radio transmitter

concealed in the heel was used to monitor secret conversations. The shoe's

transmitter, microphone, and batteries were imbedded in the heel of a target's

shoe. A maid or valet with access to the individual's clothing would be

given the job of planting the rigged shoes and activating the transmitter

by pulling out a white pin from the heel. The target would then become

a walking radio station, transmitting all conversations to a nearby monitoring

post.

As far back

as the Southern Song Dynasty

As far back

as the Southern Song Dynasty